In the 15 years since she lost her son to a single OxyContin pill, Barbara Van Rooyan has had but one up-close look at the people representing the company that made it.

It was in a small courthouse in Abingdon, Va., where Van Rooyan and other relatives of OxyContin victims gathered for a sentencing hearing in 2007. Three executives of Purdue Pharma had pleaded guilty to federal charges related to their misbranding and marketing of the powerful opioid. The company had pleaded guilty as well.

Van Rooyan and the others in her group spoke during the sentencing, giving voice to their grief and their pain. They wanted the executives sent to jail for knowingly expanding an opioid crisis fast engulfing the country.

Instead, Purdue paid fines totaling $634 million. The executives served no time. The company was allowed to continue aggressively marketing its product, and the following year, sales of OxyContin reached $2 billion.

From 1999 to 2017, more than 700,000 people in the U.S. died of drug overdoses, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In 2017, nearly 68% of the more than 70,000 recorded overdose deaths involved opioids.

“I never really thought a whole lot about evil before this all happened,” Van Rooyan said recently, seated on a couch in the living room of her Irvine, Calif., home. “But to see this kind of malevolence or disregard for human life — I don’t know what else to call it but evil.”

The outcome in that Virginia courthouse was a far cry from last week’s news of a tentative mass settlement of many of the 2,000-plus lawsuits against the company, which could total upward of $12 billion and result in Purdue’s dissolution.

The potential settlement amount would include $3 billion from the Sackler family, owners of Purdue, whose fortune is estimated at $13 billion. The family has amassed that money over the past two decades, largely by selling OxyContin, an opioid painkiller.

In a move that is central to the proposed agreement, the company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy on Sunday, and it plans a complete restructuring in which the Sacklers would relinquish ownership. Several states that have sued Purdue are expected to contest the deal.

Van Rooyan’s Purdue experience is a story of deception, sadness and frustration — yet when she tells it now, she emits a surprising spark of energy. That’s because Van Rooyan, part of the unlikely group of citizens who repeatedly took flailing swings at Purdue Pharma, is watching the giant fall.

Van Rooyan, who has studied the cases against Purdue closely, sees the paradox in the proffered settlement: Much of the payout would be financed by profits from the continued sale of OxyContin, under a new company that would be formed following the Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

But in some regard, she said, Purdue Pharma’s complicity in the opioid crisis has finally emerged into the general public’s view. “The world really knows now. They get it,” she said. “The lid is off, and all this stuff is bubbling out.”

That wasn’t the case on the night of July 4, 2004, when Van Rooyan and her husband, Kirk, got the call that changed their world. Barbara, then a professor of counseling at Folsom Lake College near Sacramento, was told that her son, Patrick Stewart, lay in a San Diego hospital, in a medically induced coma from which he was unlikely to emerge.

Patrick, a graduate of Oak Ridge High School in El Dorado Hills, Calif., and San Diego State University, died at age 24. His friends told Barbara they had attended an Independence Day party at which someone offered her son an OxyContin pill, telling him it “was kind of like a muscle relaxant and it was FDA approved, so it was safe,” she said. Patrick, who had also consumed a couple of beers, was opioid intolerant and suffered respiratory failure in his sleep.

“At the time,” Van Rooyan said, “all I knew about Oxy was that Rush Limbaugh had been addicted to it.”

She was about to learn a lot more.

Van Rooyan channeled her grief through intense research into Oxy’s vast potential for damage despite the company’s sales pitches to the contrary. A slow-release pain treatment with a heavy dose of the narcotic oxycodone, it could be easily crushed or dissolved for a more intense and addictive high. Rampant abuse already had begun to be reported, particularly in the Appalachian area, author Beth Macy wrote in her national bestseller “Dopesick.”

Later in 2004, Van Rooyan found Ed Bisch, a Philadelphia man who had begun a website to expose Oxy abuse in the wake of his teenage son’s death. The following year, Van Rooyan and her husband, a plastic surgeon, petitioned the Food and Drug Administration to require that OxyContin be made more abuse-resistant, and that its use be strictly limited to severe pain.

“This was an exhausting process, which she and Kirk did as a labor of love to try to save others,” Bisch recalled.

Van Rooyan became the California arm of a grassroots movement known as RAPP — Relatives Against Purdue Pharma. The group, originally just four in number, protested at physician meetings funded by pharmaceutical companies and testified before Congress. Van Rooyan enlisted the help of U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), who wrote the FDA on her behalf and later sent Van Rooyan a letter of commendation.

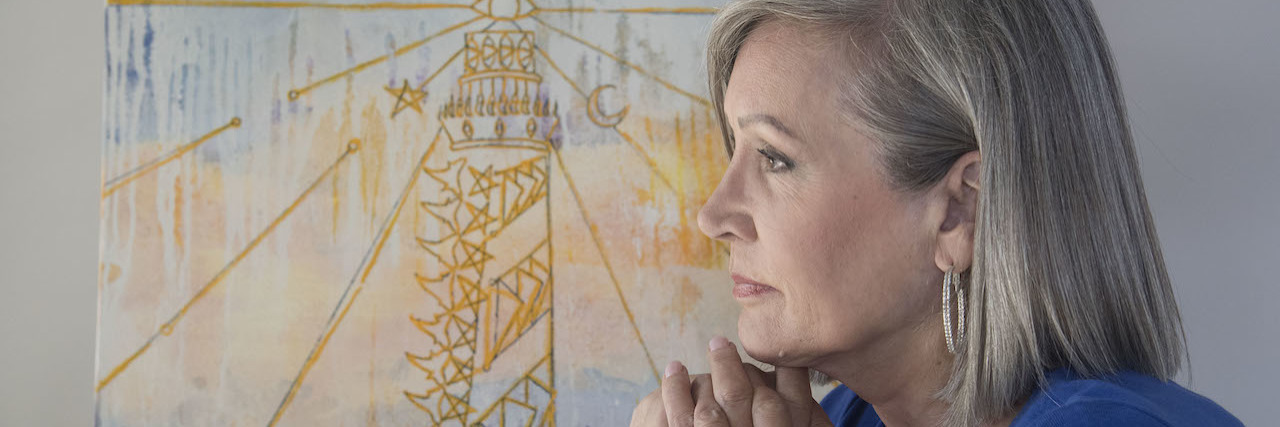

In the 15 years since she lost her son, Van Rooyan has since channeled her grief into intense research about Oxy’s vast potential for damage and has become one of the trailblazers of the anti-OxyContin movement. (Ana Venegas for KHN)

But most members of Congress did not reply to Van Rooyan’s letters, she said. The FDA said its review needed more time — which turned out to be eight years. By then, Purdue already had reformulated OxyContin to make it more abuse resistant and to renew its patent, but the FDA declined to restrict its use to managing severe pain.

Van Rooyan pressed on, but for a long while, the opioid crisis felt to her like a topic hiding in plain sight. And fighting Purdue while still grieving the loss of son Patrick was taking a toll.

“Her determination was tireless,” Bisch said, “but eventually the frustration burned us out.”

And then came the turn.

A rash of high-profile opioid overdoses and deaths, from actor Heath Ledger to Tom Petty to Prince, put the topic squarely in the public eye — and 15 years after the death of Van Rooyan’s son, Purdue Pharma and other drugmakers were suddenly on the run.

Van Rooyan tracks every development related to Purdue, including a lawsuit in New York that alleges members of the Sackler family have been offloading their fortunes into private or offshore accounts to shield them from a settlement.

But she’s not out for vengeance. Her goals have changed.

“Do I want the records to be public? Do I want these people to have their business shut down? Yes, I do,” she said. “But more than vindictiveness, I want that money of theirs to go to treatment and rehab. If that happens, something good can come out of it.”

If she has a regret, it is that the case in Virginia ended in 2007 with no more than a fine. “If that result had been different — if people had gone to jail — it could have changed the trajectory of this,” she said.

But momentum finally appears to be gathering, and Van Rooyan finds herself identified as one of the trailblazers of the anti-OxyContin movement. She spends little time dwelling on that. Instead, she quotes her younger son, Andrew, who told her, “We didn’t want any of this — this is just the hand we were dealt. We need to play the cards the best we can.”

“She’s just a really strong person,” said Kirk Van Rooyan, who has been with Barbara throughout the ordeal, though he is not Patrick’s biological father. “There have been times when I’d think to myself, ‘How would I be doing if I were in her shoes?’ And the answer usually is, ‘Not as well as she’s doing.’”

Van Rooyan, a longtime artist, now spends much of her time volunteering with veterans in Orange County, Calif., helping them get back into the workforce and using art therapy to help them express themselves.

The art is special to Van Rooyan, she said, because it is part of what saved her in the aftermath of her son’s death.

“Patrick was the one who suggested I take my first class,” she said. After a few delays, she finally enrolled. It was about a month before that Fourth of July in 2004.

Images via Ana Venegas for KHN