When I say what I do for a living, most people reply, “Huh?” I’m a rehabilitation neuropsychologist. I assess cognitive and emotional functioning in people who have had a brain injury, stroke or other neurological conditions. Then we develop a rehab plan, identifying strengths and developing strategies to compensate for any weaknesses. I love my work because even if two patients have the same diagnosis, there’s never a one-size-fits-all solution.

Other relevant stories:

• ADHD Eye Contact

• Famous People With ADHD

• How Does ADHD Affect Relationships?

• What is ADHD?

That’s why at work and at home, I always appreciated Dr. Spock’s classic advice to parents: “Trust yourself — you know more than you think you do.” After all, the brain has billions and billions of neurons, and no one can say exactly how they all work together. So when my daughter was diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) as a young child, I thought, “No big deal — I got this.” I often work with people with ADHD, focusing especially on problems with executive functioning (EF). Those are the higher-level skills that your brain uses to know where to direct its attention, for planning, time management and keeping track of what’s going on. Medication can help with attention, but EF skills often need to be taught.

All was well and good, until my daughter was in middle school and forgetting to write down her homework, or writing it but forgetting to bring the right books home, forgetting to do the homework, and/or doing it but forgetting to turn it in, and her school was not implementing the structure that could lighten the EF load. One day, in a particularly low moment of frustration (along with a building panic at the thought that maybe she might not make it out of that grade, let alone high school), I said to her, in the most non-therapeutic tone possible, “How could you have forgotten your homework again?”

To which she replied, “Mom! I have ADHD!”

And she was right. Luckily, there was one person in the room who understood brain-behavior relationships, because the higher levels of my brain, drenched in a cascade of cortisol (the stress hormone), had apparently made an executive decision to go out for lunch, leaving the “primitive” part of the brain in charge. All the knowledge I routinely share with people at work, encouraging them to be understanding of ADHD symptoms rather than rage against them, went right out of my head, replaced by the fear that maybe I didn’t know what I was doing and if I didn’t get things under control soon, the doors to my daughter’s success in life would be slammed shut.

Hence, my question whose answer was obvious. But perhaps it wasn’t a total #ParentFail, because my daughter had somehow developed a better sense of herself at 13 than I had at her age (or let’s face it, at 30). She understood what she was dealing with and had learned to advocate for herself. So perhaps it’s time to propose a corollary to Dr. Spock’s adage: Trust what they know.

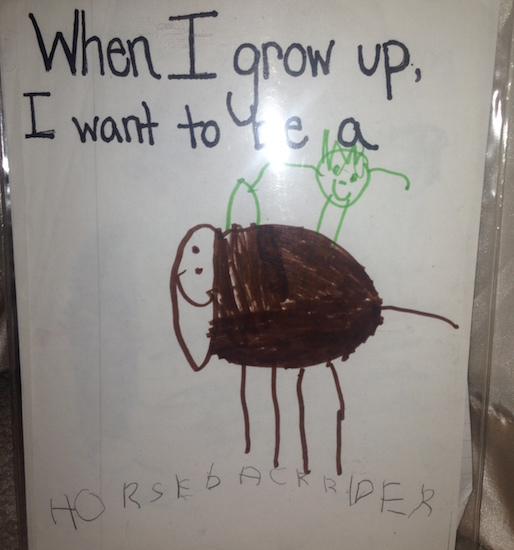

As in, trust that a pre-kindergartener with an inexplicable fondness for horses might know what she’s talking about when she draws this picture:

Let me explain. We are not a “horsey” family, but because my daughter was obsessed with horses, I signed her up for riding lessons, figuring she’d try it for a while and then her interest would fade. Not quite. Somehow, this child who seemed at risk of missing the entire 7th grade curriculum could focus for hours when she was riding and never forgot any of her gear (excuse me, her tack) when packing for lessons. And at school, she found wonderful teachers who encouraged her to write almost every essay and do every art project about horses (or so it seemed). Twelve years later, she is applying to colleges with equine studies programs — something I didn’t even know existed when I was having my middle-school meltdown.

So after years of education and experience in neurocognitive functioning, now I can add my two cents to the unending stream of advice for parents of children with disabilities. Maybe I should have known it once I had my doctorate, but it took a kid with a disorganized backpack and a clear mind to set me straight: Brains may be “neurotypical” or they may have all sorts of idiosyncrasies. Who knows exactly what each child’s path in life will be? But generally speaking, if you’re a good enough parent that you’re worrying about it, I believe your child will be fine. You can deal with any problems that arise. But first, take a deep breath. Sometimes you just have to trust that the kids will be all right — if you can avoid panicking, trust them to discover the things they’re good at and then basically stay out of their way. Especially if they’re on top of a thousand-pound horse.