What Taylor Swift's Latest Album Means to My Mental Health and Self-Worth

There are times when “letting it go” is easier said than done.

First things first: yes, that was a “Frozen” reference, and yes, I am a dedicated fan of that Disney motion picture.

As familiar as I was with “Frozen” immediately following its release in 2013, I didn’t get around to watching it until I was on a flight from London to Philadelphia in 2016. I couldn’t have timed it better. In the twelve months leading up to my transatlantic flight, my life had changed irrevocably – mainly for the worse – and the myth I’d constructed for myself about who I was had been burned to the ground. The parallels between my life and Elsa’s character arc in the film immediately became clear to me.

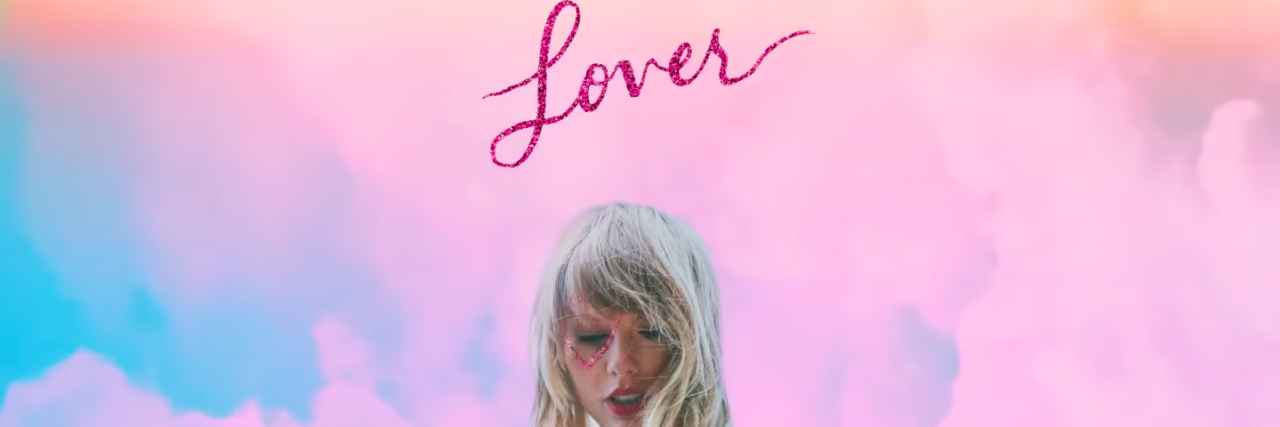

It’s also no accident that I’m writing this after the release of Taylor Swift’s “Lover,” her seventh studio album. I’ve been a Swiftie for ten years now, and I’ve spent that time analyzing all her lyrics and marveling at how detailed and relatable they are. Towards the close of “Lover’s” final song, “Daylight,” Taylor sings: “step into the daylight and let it go.” “Frozen” reference or not, I already consider this to be one of her most profound lyrics ever. She’s been subjected to so much unwarranted criticism for the last ten years for almost every aspect of her professional and personal life, with interviewers grilling her about things that happened three, four or five years ago – almost as if baiting her to say, Everything bad in my life is 100 percent a result of things I’ve done wrong.

I say that this sends a toxic message to everyone out there who struggles to accept their self-worth. If you feel (or, perhaps, have been maliciously led to feel) like you’ve got lots of reasons to doubt yourself, then being persistently reminded of things that happened to you relatively recently or a long time ago – especially when the events that hurt you may not have been directly instigated by something you did – can be a very nasty obstacle to moving forward. This is an idea that hasn’t received nearly enough attention or understanding in recent years. Hence the subject of this piece: “when letting it go is easier said than done.”

Therefore, I’d like to share three examples of when I found it hard to “let it go.” In some cases, I’m still trying.

1. When it dawned on me that I’d essentially been on probation for my whole life – and my only “crime” was being on the autism spectrum.

School reports are, and always have been, an essential aspect of life for all pupils and parents. My reports didn’t just feature the comments about my progress in all my subjects, they also included remarks about my development against social targets. How was I interacting with peers in and out of the classroom? Was I getting better at resisting the temptation to complain about every single bad interaction? How well was I conforming?

None of this is intended as a slight to my teachers or parents – they did excellent work with me over my school years, and all things considered, it did bring positive change to my life by the time I completed my GCSEs when I was 16 years old. But that positive change was chiefly on the outside. On the inside, I’d resented this additional monitoring. None of my close friends were subject to this additional monitoring. Of my peers of supposedly similar academic ability to me, none were subject to this additional monitoring either. Years later, I saw the (hitherto confidential) reports written about me – and all my worst fears were confirmed. I’d always seen myself as a failed outsider with few redeeming features; these reports confirmed my fears. No wonder I’d always questioned (to the point of overanalysis) every single decision I’d ever taken and every word I’d ever said.

I slowly distanced myself from this autism monitoring after I started my A-Levels and then went to university. I tried to turn my quirks into positive, proud aspects of my persona, which has helped me to find the best, most understanding friends I’ve ever had. I even became secure enough with my autism (Asperger’s) to start writing about it in public – at which point I was promptly told to stop advertising it. There was no other way to spin this than “it really is a character flaw after all,” and this still stings.

I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to let that go. I don’t believe it really is a character flaw, but it still hurt to hear it.

2. When my application to study at the University of Oxford ended in rejection.

With my aforementioned autism – and autism monitoring – in mind, my academic work was my main driving force throughout my school years. I was consistently considered to be in the top 10-20 percent of my year group for academic ability, and my excellent school mostly encouraged me to aim high. “At least I’m academically strong,” I often told myself. To this end, I set my sights on an Oxford degree in mathematics or chemistry.

In July of Year 12 (when I was 17 years old), I decided to apply to study chemistry at Oxford. My school supported this decision and put me through an extremely rigorous program of refining my personal statement and attending academic enrichment courses. This led to my being invited to Merton College, Oxford (my first choice college), for interviews that December; my heart was set on getting accepted into this college.

I’d been told not to read too much into “how well did the interviews go?” on the spur of the moment, so I didn’t. My gut feeling, however, was I’d had a good, a not-so-good and an incredibly weak performance over the course of my three interviews, and an OK performance in a follow-up interview at Exeter College the following day. Alas, three days later, I got the email that closed the Oxford door on my life – and my long-standing academic rival got the email welcoming her into Oxford (albeit not for chemistry).

This one was relatively easy for me to let go, because I still had good offers on the table from four other great universities. I accepted one of these offers, threw myself into my chemistry degree once it started, and quickly made better and closer friends than I’d ever been able to in my school years. The Oxford rejection was still very painful in the immediate aftermath, however – I’d leaned for so long on my academic work as my only passport to the world, and it had suddenly received a big rebuke. Still, that regret lapsed when my university years started, and new doors opened that wouldn’t have opened anywhere else. Speaking of which…

3. When I was emotionally abused during my last year of university, and my graduation suffered for it.

This one is the biggest and worst experience I’ve ever had of questioning my overall worth.

At the end of my third year of university study, with one year left until my graduation, I was on course to achieve a First Class degree – the highest possible degree classification. For my final year, I had to complete a long chemistry research project, involving 40 hours of laboratory work per week. Practical work had never been my favorite aspect of my studies, but I had always followed all instructions to the best of my ability. From day one, this wasn’t enough for the Ph.D. scholars who were working with me in the lab; they would always find a way to bend the lab rules to frame me as incompetent. They spewed venom about me while talking to their friend, knowing I could hear everything. They shouted at me for doing something wrong, and also for doing everything necessary to avoid doing the wrong thing. My self-constructed myth – that I was academically strong – collapsed, as did my mental health.

My interest in my project also plummeted, as I found it easier and healthier to keep my head down than to raise a lot of ambitious ideas and risk further verbal torment.

Any chance I had of securing that dream First Class degree slipped away

equally quickly; 25-30 percent of my peers did graduate with “Firsts.” When I walked the stage at my graduation, I felt absolutely no glory. I just felt like I’d ticked a box without anything to show for it, after four years of study and the preceding 14 years of school work. I even started suffering nightmares about my lab experience.

I had a clear path worked out after my graduation, which made it relatively easy to move on, and that clear path has since led me to the excellent job I now hold. However, letting my lab experience go has been another tall order. It’s hard not to be reminded of it every time I mention “lab work,” “university” or “graduation” – or any time I engage with an authority figure. I know it’s not a realistic fear, but I’m still always on guard against being shut down like I was most days during my lab experience. Just like it’s hard not to be reminded of my autism monitoring whenever I want to suggest an idea or put anything in my diary.

The best way I’ve found to put them in the back of my mind – not quite letting them go, but the next best thing – is to spin them into positive aspects of my character. I’m empathetic, I hate seeing people hurt, I love overemphasizing the things I love that make me who I am and I love celebrating the fact that my university (which wasn’t Oxford!) helped me to realize all of these things. I refuse to let the worst people from my undergraduate years overshadow the best people I’ve ever met.

Elsa discovered how to control her demons and let them go. Taylor Swift recently reminded us that “letting it go” does not necessarily have to mean forgiving and forgetting. Combining these two approaches gives a pretty good description of my coping strategy. I don’t know if it’ll be completely infallible every single time, but when it works, it really works. That’s a win.

Screenshot via Taylor Swift YouTube channel.