Screen time is the nemesis many therapists, teachers, doctors and friends tell you is the worst possible thing you can give your child. When we’re out, I see how people look at me and judge my parenting because my child is watching a video while we eat. I see how they shake their heads and whisper about how I must be a lazy parent not to just engage with my child while we eat. I see it all, and I’m screaming inside that I see the judgment. Prior to having my son with special needs, I was the same as them. When I saw parents allowing their child to do this, I would think the same thoughts. Then I was given a child like Von.

My child was born with a complex disease. The disease nearly killed him when he was 3 months old. He hadn’t been diagnosed yet, and he spent a week on life support clinging to life as doctors tried to figure out why all his organs were failing. When he finally got diagnosed, the damage was already done.

He had prolonged low blood sugar for more than 48 hours, and it dipped as low as seven when he was the most critical. A blood sugar of seven would kill most people. It did not kill my son, but it did damage his brain. Doctors told us, “Your child will never be Einstein.” They talked about “learning disabilities” and “developmental delays.” He was just a tiny baby then, and at the time I ignored it.

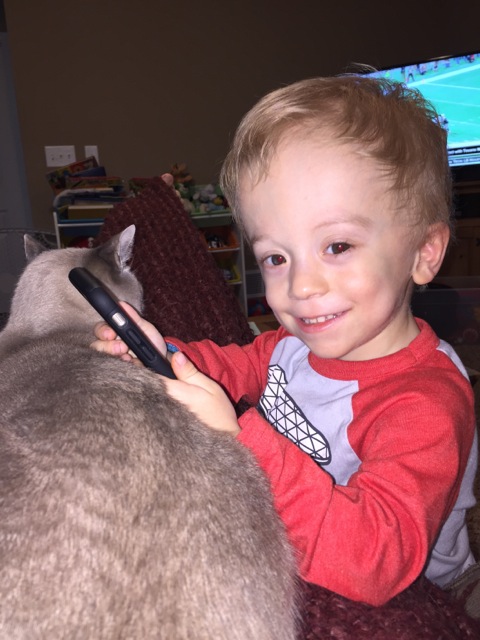

As he grew, he fell further and further behind his peers. He seemed to respond excessively to movement, and he would avoid touch and texture. He became obsessed with cars, trains and trucks. While other children were playing with toys, my son was itemizing them, lining them up and organizing them by type. He didn’t know how to play, socialize or eat. We tried everything — every single thing you can imagine, every food, every technique — and there was always a strong pursed lip and head shake when food came close to his mouth. Then one day we gave him a phone. He was able to distract himself with an entertaining clip on YouTube or silly dog video. We could sneak the bites in and encourage him to chew. After months of exhausting so many possibilities, we sought therapy with professionals to help.

The therapists said, “Your child has apraxia of speech, oral apraxia, severe oral aversion and sensory processing disorder.” I looked at the therapist and had no idea what any of that meant. They explained he’s so overwhelmed by all the things around him that he can’t effectively process motor movements in his mouth, he’s unable to chew and swallow because he can’t coordinate it in his brain, and the only way he can do any of this is if we make the process automatic versus planned. It finally made sense.

All this time, and all those judgmental looks from friends, family and strangers, and I had somehow known my child well enough to know he had to be distracted. If Von had to plan it on his own, his brain can’t do it. He can’t chew if he has to think about it. He can’t speak if he has to think about it. Everything must be spontaneous, or he has to be significantly distracted by other things to do basic skills.

I asked the therapist if it was OK for him to watch a screen while he ate. She told me he has to eat, and until we can help him learn to master this skill on his own, everything in our home should stay status quo. We shouldn’t interrupt meals and expect him to sit still and eat without distraction. He needs distraction to eat.

I felt validated when she told me I wasn’t being a bad mother for allowing this behavior. However, it doesn’t mean those looks I get when we’re out don’t sting any less. I know people think I’m a lazy parent and judge my choices. I see the comments on social media, and no matter how hard I try to not let it affect me, it does. Parents of children with oral motor processing disorders have to do things differently. It wasn’t even something I knew about before being a parent. I didn’t realize how hard it was to chew and swallow. I didn’t realize touching textures would be so hard for my child that he wouldn’t feed himself. I had no clue he would lack coordination to lift a spoon to his mouth to feed himself.

I know it looks strange to see a 3-year-old being spoon-fed by a parent or to see me fight him to open his mouth to eat. Or when you see me put my finger in his mouth to scoop out the bolus of food from his cheek — I see those looks. What we’re doing isn’t normal. However, we’re doing our best to allow him to grow and thrive. We are all determined to help him learn to eat, because a feeding tube would be a step backwards for us.

Next time you see a parent like me struggling with their child to eat, instead of judging, maybe give them a sympathetic look or a high-five and tell them you understand. Let them know you aren’t judging them. Eating disabilities are real. They’re hard on all members of the family. Be compassionate, and remember we are all just doing our best.

Follow this journey on Von’s Super Hero Facebook page.