As the parent of a child with autism, there are things I just don’t experience the same way the parent of a neurotypical child might, and it can be disheartening. Though guilt rises up in me admitting this, when approaching some situations, I’ve asked myself, “What’s the point?”

In May, my husband and I had plans to take our son, who’s on the autism spectrum, to see “Frozen on Ice.” My son came down with something, and we took him in to see the on-call doctor who prescribed medication for him and then went on to say that we probably shouldn’t take him to the show. “He’s not contagious,” she said. “But it’s a better idea to stay away from crowds so he doesn’t pick up something else. Plus, he doesn’t really understand so he won’t know what he’s missing anyway.” I saw red and stopped listening, calmly excused myself, and made it to the car before my husband and I both shared tears over her tactlessness.

She said this garbage in front of my son. She had “known” him for about five minutes. And in that small amount of time, she determined what he could understand and what he couldn’t. She assumed.

I seethed. My son loves “Frozen.” He loves Bubble Guppies. He asks to go bowling and to go to the beach. He picks certain foods and avoids others. He’s not “stupid.” He’s not unresponsive. He’s alive and well, and he’s a person with likes and dislikes just like you and me.

So we took our son to see “Frozen on Ice.” And he watched. And he smiled. And in my head, I punched that doctor in the throat. Because on every level, human and professional, she was dead wrong.

Friends and family members jumped to defend me and shared in my anger when I posted about the situation on Facebook. They supported me and commented on all the pictures of William clapping along with his favorite “Frozen” songs. He wasn’t 100% himself because of his ear infection, but he had a couple of days of antibiotics in him by the time we went and damn it, we were going to “Frozen” on principle alone at that point.

One of my friends genuinely asked me via private message, “Would William know the difference?” I thought about it. He had never been to the Amalie Arena. He had never seen any show on ice. He had never seen a person ice skating, come to think of it. That had nothing to do with autism, though. So I told her he understands we are seeing “Frozen.” I told him it’s in a big arena. I told him we’re going with his aunt and his daddy. He could think we’re just going to watch the movie. But couldn’t any 4-year-old think that? Any child might not be able to picture or grasp something brand new to them. And I like to think even if he couldn’t picture the entire setting, he was looking forward to it.

I think people, like this on-call doctor, often believe there is no point in attending big events or attempting to celebrate holidays with children with special needs. Because they don’t react the same way. Or they can’t experience it in the same way. But this is funny to me because how many people do you know who take their infants to Magic Kingdom to meet Mickey Mouse, something that a barely walking child will have zero memory of? How many spend hundreds or thousands of dollars on Christmas gifts for a child who will forget the toys and play with the boxes? How many parents and grandparents take toddlers to the zoo, pointing out animals and trying to teach them new words even if they’re distracted by other things? How many of us throw Pinterest-inspired first and second and third birthday parties that are really more for the invitees than the guests of honor?

Here’s the thing: memories aren’t just for the child. They’re for the parents, too. We do these things to see our children smile, sure. We do them to build our families. And we do them to make ourselves happy, too.

Every year, I’ve selected William’s Halloween costume. I remind him how to say “Halloween,” “trick or treat,” “pumpkin,” and other seasonal phrases. But it’s hard repeating myself year after year. I shouldn’t be teaching my 4-year-old to say “trick or treat” when that was all he could say two years ago, right? It’s hard. But you know what? He is what we have. He is who we have. His abilities are progressing every year. So we embrace it.

He was an astronaut. Then Jake and the Neverland Pirates. Then Danny Zuko from “Grease.” Then Albert Einstein. This year, because he loves watching baseball — specifically, the Tampa Bay Rays — I decided to buy him a Chris Archer jersey, find some baseball pants and cleats, and make him a Tampa Bay Rays player. I knew he would like it. I’ve enjoyed making those memories, not just for him, but for me and my husband and our family members and our hundreds of Facebook friends who think William is pretty badass.

But this year, I faced a couple of obstacles…

One of my friends asked me about William picking his costume. Though I’m pretty open about our challenges, people — out of both ignorance and sheer curiosity— ask questions or make comments that remind me that we’re different. I got sad. Would he ever pick his own costume? Should we even try? What’s the point?

Then, William all of a sudden developed a sensory issue with button-up shirts. I started worrying that the jersey thing wouldn’t happen. He wouldn’t wear it. Should I even try to get him to wear it? What’s the point?

On Labor Day, my husband and I took our son for a ride to the Spirit Halloween store. I thought maybe, just maybe, he’ll walk up to a costume that catches his eye.

Wrong.

My son, like always, wanted to run up and down the aisles over and over again. He wanted to push the button that awakened a screaming banshee hanging from the wall over and over and over again. He wanted to see the red lights on the zombies and the smoke coming out of the wolf’s mouth.

I sat on the floor of an aisle and texted my best friend while my husband chased my son. “There’s no point,” I sent her. No point in asking him to pick a Halloween costume. While little boys and girls around me pick their Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle and Elsa costumes, my little boy repetitively pushes buttons and runs in circles. Oblivious. I spiraled. No point in Thanksgiving. No point in Christmas. No point in Easter. No point in birthdays. He doesn’t even notice. I felt tears coming.

Then a text message came in.

“He’ll get there,” she answered. And she was right.

I stood up, put on my bravest face, and walked toward where my husband and son stood. I was determined to try, and I was determined to not fall apart if my attempt failed.

I took my son’s hand and said, “William, first we need to pick a costume. Then we can push the button.” He said, “Push button.” I said, “First, let’s pick a costume.” And I had an epiphany. Choices. Too many choices.

I walked up and down the aisles and selected things he would recognize. “Look, Will, it’s Woody from ‘Toy Story!’” I said. “Cowboy,” he said. “Look, it’s Superman!” “Superman!” he repeated. “And this is Dracula from ‘Hotel Transylvania.’ We watched that night.” I did my best Dracula impression,

“Dracula bleh, bleh, bleh.” And he laughed. “And this one over here is Hiccup from ‘How to Train Your Dragon.’ He’s kind of like a knight because he’s wearing armor. We’ve seen both of those movies.”

I put all four costumes on the floor. “Do you like any of these?” I asked him. He pointed. Pointed with his finger. Which he never does. Anyone who has a child on the autism spectrum can understand the celebrations that come with seemingly meaningless milestones like this one. He pointed at the vampire costume and said, “Dracula bleh bleh bleh!” And he smiled.

He picked his costume, guys. For the first time. He probably didn’t pick it like other kids might. But he picked it.

We did the parent thing and put the shirt, pants, and cape on — just to make sure — which he yanked a couple of times, and then we distracted him by giving him what we promised: the chance to go push the button to make a monster scream.

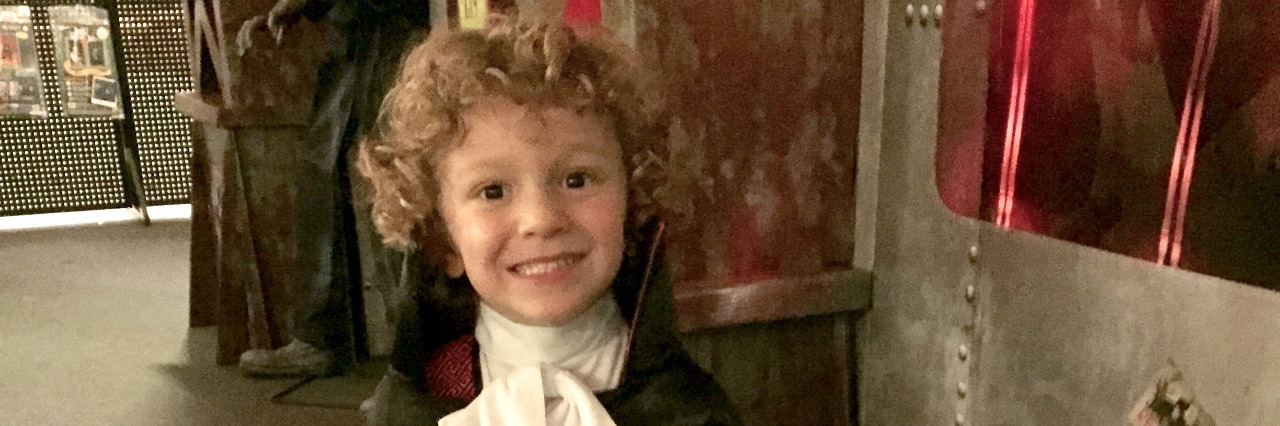

Either way, he ran through the store, his Dracula cape flying behind him. He pushed the button, flapped his little arms excitedly, and left the costume on for another 20 minutes. It’s a winner.

Sometimes, it seems like there’s no point. It seems like he won’t understand. It seems like we can’t experience the “normal” things. But really, there’s always a point. Always. Because he’s the point. And he’s a seriously cute Dracula… bleh bleh bleh.