As a former police officer and mother to a child on the autism spectrum, Stephanie Cooper knows how important it is for police officers to be able to recognize autism. To help ensure safer interactions between the police and people with autism, Cooper started Autism Law Enforcement Response Training (ALERT), a training program for police officers that provides officers with sensory kits designed to help autistic people.

“People with autism have communication issues, and law enforcement officers need to be aware that their typical approach when responding to a call or an emergency situation with someone with autism spectrum disorder may not work,” Cooper told The Mighty. “By the police being aware of people with autism it helps ensure the safety of not only the person diagnosed with ASD, but the police on the scene as well.”

Cooper created ALERT after watching a police officer interact with her son, who’s on the spectrum. “When the officer arrived [my son] was having a sensory overload,” Cooper recalled. “The officer luckily understood about autism and helped me keep David calm while we filed the report. But it got me thinking what would have happened if the officer did not know about autism.”

Cooper asked the officer if his department had any autism training programs, but it did not. Wanting to ensure more positive interactions between law enforcement and people with autism, Cooper began researching autism training programs for police. “I realized even though there are some training programs out there for the police that there are still not enough training programs available to assist every law enforcement agency,” she said. “So I offered to train my local police agency, and it all started from there.”

As part of ALERT’s “Autism 101” training, Cooper trains officers how to recognize a person who has autism, what behaviors they may exhibit, what types of calls may be received and tips for how to interact with a person on the spectrum.

“Officers [should] know that an autistic person may flee when approached by an officer, and fail to respond to an order to stop,” Cooper said. “Officers should not interpret any of these actions regarding an individual with autism as a reason for increased force. Officers [need] to take their time when dealing with an individual with autism, to allow for delayed responses, to speak slowly and clearly to an individual with ASD and to be aware that autistic individuals react to their environment.”

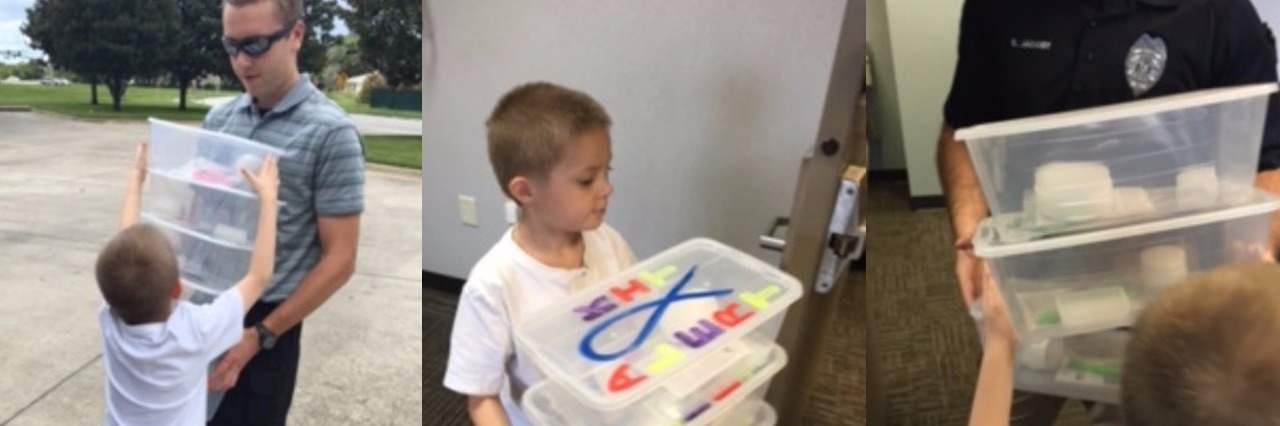

Once they’ve completed “Autism 101,” officers receive a kit filled with items designed to help people with autism, such as visual communication cards and a variety of calming sensory items.

So far ALERT has provided training and more than 100 kits to law enforcement agencies in Cooper’s home state of Florida. In December, Cooper will be training the Hammond police department and the Tangipahoa Parish sheriff’s office in Louisiana, and handing out 200 autism sensory kits.

Beyond Florida and Louisiana, Cooper is working on expanding ALERT into a nationwide initiative, with the goal of training and giving kits to law enforcement agencies in every state.