What a Letter My Mom Wrote About Raising Me as a Child With Autism Means to Me

When I turned 24, it really didn’t mean much to me besides knowing that in a year I could rent a car for the very first time. Two weeks later, I received an email from a parent in regards to helping her grandson who has Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS).

Maybe more than any of the other emails I had received before, this note was very detailed, asking several questions about topics such as early diagnosis, therapies, early childhood, how to approach the diagnosis, etc.

Even though I’ve helped answer questions before, I asked my mom to help assist me in answering this woman’s questions. What I received back from my mom made me realize it had been 20 years since I was first diagnosed at age 4.

Twenty years of autism.

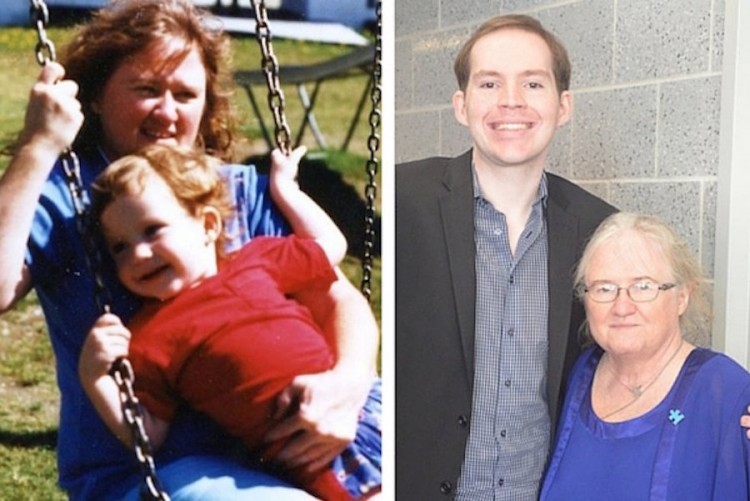

It made me realize how much time had flown by and how I got to where I am today. I thought about the milestones I’ve hit: playing for my high school basketball team, being student council president, having a girlfriend, graduating college, becoming a motivational speaker, writing a book and, maybe most importantly, having a voice to be heard. Time slowed down for a bit.

This is what my mom wrote to the woman who was seeking advice about her grandson with PDD-NOS:

“Looking at Kerry today, I wish someone had offered me the inspiration and hope that he represents 20 years ago. And I can see why anyone would ask him how he got to where he is today. His PDD-NOS was severe. Although we didn’t know what PDD-NOS was at the time, they mentioned that some children were institutionalized, and that’s all I heard.

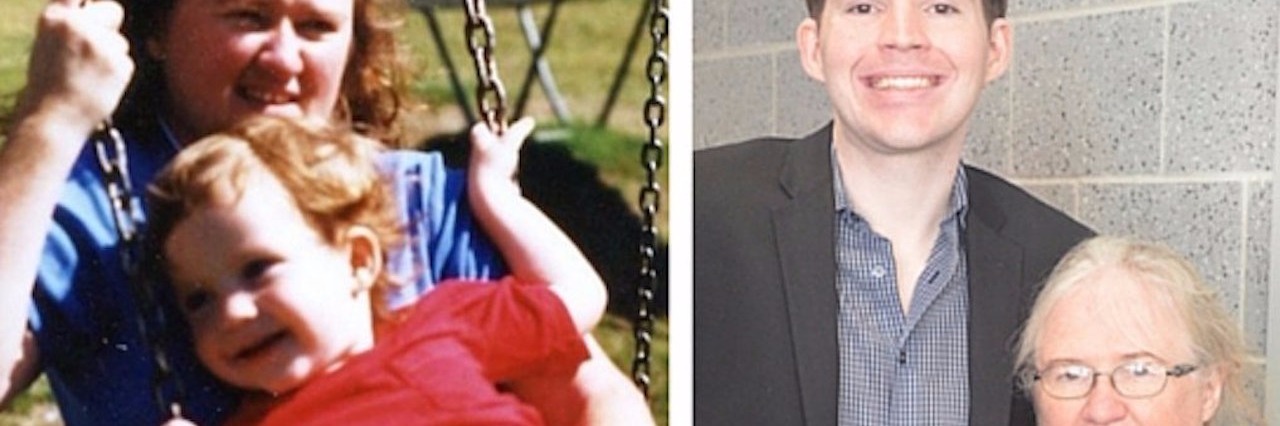

Kerry was our delightful only child who reached most development milestones like height and weight (except speech) until he was 2 and half years old. At 2 and half, he started to show extreme signs of sensory integration dysfunction, where he was afraid of a wide variety of sensory issues. Wind, rain, water, noises loud and soft were major issues.

There was a time when we couldn’t bathe him. Uneven surfaces such as sand or swings where he couldn’t feel the bottom below him were a problem. He was asked to leave two different preschools because they couldn’t handle him. He preferred isolation and wouldn’t play or participate with other children. He had delayed speech, limited pretend play, twirling and extreme difficulty with transitions and tantrums. He also had fine and gross motor delays.

When I dropped him off at school in the morning, he would scream that he didn’t want to go in, and when I picked him up in the afternoon, I would have to drag him screaming because he didn’t want to leave. Once at home with a caregiver, he would scream at the top of the stairs, “Go away!”

Kerry was diagnosed first by Hackensack Hospital and then by Dr. Margaret Hertzig, the director of pediatric psychiatry at Cornell. Dr. Hertzig is a world-renowned expert in autistic and autism spectrum disorders. She watched him as he grew, marking improvement she observed.

The Kerry you see today is not the Kerry I grew up with. We began occupational therapy (OT) at home with a pediatric therapist. OT continued at home until he was 7 as well as in school where he was in a multi-handicapped class. At 7, he began intensive physical and OT therapy at Hackensack Hospital where he did a lot of vestibular planning issues. He is seen privately to this day for OT/PT as needed by a local physical therapist.

One of the major things that worked for us was sports. Although he didn’t want to be around people, I got him involved in pee-wee bowling and then sent him to a JCC summer camp for children with neurological issues. The camp was wonderful in that they did a different activity every 40 minutes, and the forced transitions helped condition him a lot. The vestibular planning therapy also helped a lot.

Kerry started to respond to recognition, praise and rewards, and I ran with that. We have a million “great job” stickers, magnets and trophies. I also developed my own token economy barter system with him. If he would try something three times, he would get a predetermined prize (seeing a movie, an action figure, a game) that we agreed on. If after the third time he didn’t want to do something, I would agree to let him drop it. When he wanted to do nothing three times, it sometimes seemed interminable for both of us, but I kept at it and found a kid who loves bowling, soccer and basketball. T-ball was rougher with the coordination issues and was one that got dropped but not until the third season.

All this time, speech, physical and occupational therapies continued. He also took lessons piano at the house to help him out.”

To have this letter written out for me to read left me with so many emotions. Some of these things happened so long ago, I had no recollection of them whatsoever. What stayed with me, though, was the passion and love that came with this letter. No matter how many challenges were presented, my parents were always willing to go the extra step to help me, and today I want to live by that example to help others.

My parents are strong. They are saints. Without them, I have no idea where I would have been five years down the line let alone 20. I know I still have a long way to go, but one thing I know is for the next 20 years that I have autism, I’m not going to be sitting down. I’m going to fight, I’m going to serve, I’m going to commit, I’m going to conquer and I’m going to communicate for the better day for us now and for the future.

I wrote this blog post several years ago, but the lessons I’ve learned from my parents still rings true today. To all the parents out there, remember you are your child’s greatest advocate.

This post first appeared on KerryMagro.com.