How I Found Catharsis Living With Bipolar Disorder

Editor's Note

Please see a doctor before starting or stopping a medication.

Any medical information included is based on a personal experience. For questions or concerns regarding health, please consult a doctor or medical professional.

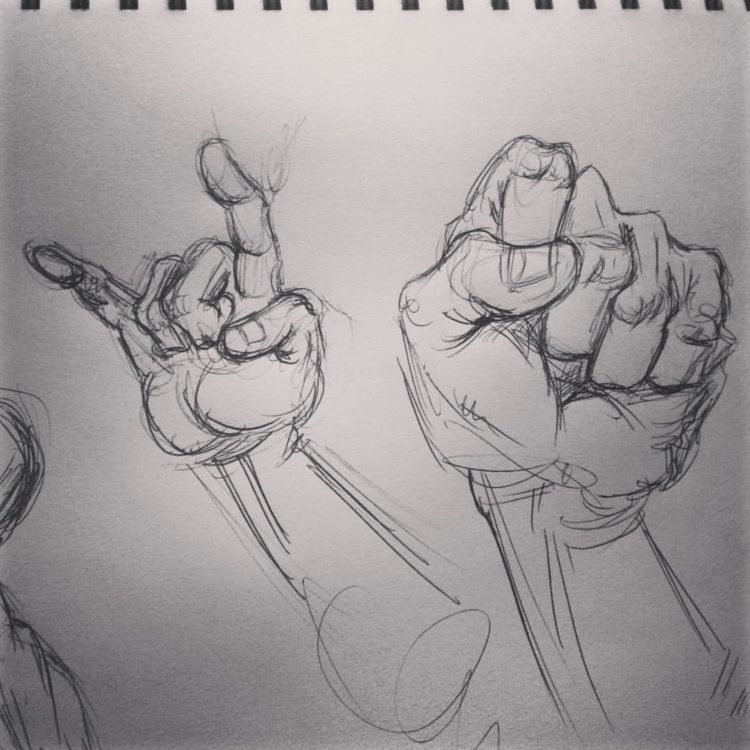

When I was a kid, I was always drawn to drawing and the arts. I have memories as a 2 or 3-year-old drawing at a table in a bath of warm incandescent light, listening to the hum of my grandmother’s dimmer on a vase-shaped light with crystals dangling from the lampshade. I was an overly energetic kid. My father affectionately called me, “The Mouth With Feet,” which was a perfect description of how I was behaving. I’d do impressions and have long conversations with adults for hours on the phone. They would all say, “What a wild imagination!”

• What is Bipolar disorder?

And I did have one. So much so that I started hallucinating and having night terrors as early as 8 years old. A few years later when I was around 10, I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. To my family’s surprise, the “energetic kid” had something “wrong” with him. Remember, this is in a time where SSRIs and antidepressants were first being introduced.

I was hospitalized a few times after that, between the ages of 10 and 16, after a suicide attempt and reckless behavior. I was expelled for fighting and put in a behavioral school, which was more like a JV halfway school than anything resembling an environment to cultivate a young mind. I had to come to terms with the “new me” while at the same time dealing with being a social pariah battling the demons of puberty and acclimating to the sudden surge of testosterone as my system was trying to reach some sort of homeostasis.

I was also heavily medicated. Some might even say sedated at times. The once vibrant light my family saw in me was beginning to dim and leave behind a dull patina of the person I “used to be.” I made the conscious decision to try to find something in life to give me happiness besides pills as they clearly weren’t cooperating with my shape-shifting teenage body. I turned to music and playing drums in a metal band. I turned to paintball and skateboarding. But no matter what I did, something was missing.

I was accepted a year early into a commercial art vocational program at a nearby high school, which got me out of the behavioral school and reassimilated me to public school. This is where my life started to shift. I’ve always listened to music as an escape, and even turned to playing it. I was always watching movies, drawing and, of course, playing sports. But the idea I could use my art as something to provide for myself and others was a new concept. Once joining this program, that all became a possible reality in my mind.

However, it wasn’t without sacrifice. Trying to be good at representational art is more of a crawl than a sprint. It takes patience … which is a quality I’m not particularly known to often have. The frustrating task of learning anatomy and landmarks became a bit of a prison as it took something I loved doing for escape and recreation, and made it into rigorous, detail-driven work. But I could lose myself in that work, and that was good enough for me.

Because of this program, I was able to get a scholarship to a respectable art college in central Ohio. I was very excited to be in a new place on my own, away from all the folks I had known before. A fresh start.

One small problem. My medication was off. I began falling asleep in class. Not like in high school due to depression or lack of interest, but this time it was because of sedation. The pills were off. The irony of finally getting to a place of enjoying and appreciating education only to have my body fail was not lost on me. I made the decision right there to go off of my medication. Now, might I preface this next part by saying I do not recommend for others to follow in my path. This was a reckless decision I paid for later. But ultimately, it was the best decision for me.

In many ways, college was more beneficial for me from a social standpoint rather than an academic standpoint. I was finally getting real feedback from strangers not tinged by the stain of my disorder or past. I was able to color outside the lines and learn how to become a productive member of a social circle, and ultimately, in society at large. I remember the first week I was off the meds: I was overwhelming to be around. I experienced an intense mania that felt supernatural. I was hyperactive, hypersexual, reckless and impulsive.

As some college students do, I self-medicated my symptoms with alcohol for quite a while. Eventually, I was able to use that unbridled feedback to my advantage. I started to mellow out and take life as it came with the ability to recognize the symptoms of my mania or depression and regulate them with exercise and creativity.

Looking back on it all, the one thing that saved me from reckless manic behavior and swings into debilitating depression was the work. The workload was overwhelming, and I finally was excited and eager to do the work. At this point, my interest in fine arts was turning into an interest in music videos — editing, shooting, storytelling and eventually directing.

The technical side of things was my busywork as the storytelling fueled the fire inside of me and I became obsessed with work. This is where I learned my superpower. The sweet spot when you ride the mania out of depression. Sometimes called the CEO disease — it’s the productivity zone. It’s where you feel invincible, but your ego is in check enough to still keep the antenna tuned into God’s radio station.

Fast-forward to today, I am now a working filmmaker in Los Angeles and things are not too different. I still use work to balance my symptoms out. The only difference today is I’m mature enough at 32 years old to know my demon’s triggers and how to scratch the beast just right to calm him down.

Another thing that has helped along the way is the ability to tell stories about other folks dealing with their own demons of mental illness. Their stories are not like mine in the script, but have a familiar, almost mythical, arch to them. They all experience adversity, and use something greater than themselves to deal with their struggles.

Remember that art I drew 10 years ago? Well I used to try to replicate composition and line work by a prolific artist named Derek Hess. Eighteen years later, I was lucky enough to make my first feature, a biographical film on that very artist.

And remember that angsty teenager in the psychiatric hospital at 16? That was a particularly dark time. I attempted suicide and was held involuntarily (a 5150) and kept for monitoring. I did not want to be there. The one thing that got me through it was the DVD from a band called Chimaira. His lyrics spoke to my soul, echoing the anger and helplessness I felt.

Little did I know back then that over 16 years later, I’d be lucky enough to make a film on that artist I was a fan of or that vocalist and his struggles with mental illness. If I would have completed that suicide attempt, this blog post and all the art I’ve been lucky enough to create would not exist. It’s a perspective-shifter.

I’ve been lucky enough to turn my feelings of depression and worthlessness into positive ones of empathy and expression through my work. I’ve been able to help others in some small way by sharing compelling stories. I’ve been able to make lifelong friends and build deep relationships with my crew on set.

I’ve been able to give my struggle meaning.

Go out there and fail forward. Learn from your stumbles and regain your footing. Life is a journey for all of us and whatever you can do to channel your frustrations or perceived weakness into a creative strength will only benefit your life. My journey is not yours, but the principles here stand strong.

I share my story not as a humblebrag, or a pat on my own back. But in some ways I share it to help the younger version of myself who is out there now, confused and alone. I wish I knew someone like me back then, someone who would just assure me I was not alone and I was not a “freak.” More so, someone to tell me if I stayed the course of conviction in my art, it would lead to emotional catharsis and recovery. I had to discover my self-worth through passion leading into purpose. But it sure would have helped to have had someone to say, “Everything is going to be OK.” And it turned out … it is.

Original photo by author