How Art Became a Window Into My Sister's Struggle With Borderline Personality Disorder

“I threw two dishes on the pottery wheel today, which made me feel very happy. It feels good getting my hands wet with clay and making beautiful things with my own hands. It’s amazing. I’ve been sober for two weeks now, please God help me to be sober for the rest of my life, which will be long, hopefully. I want to live!”

— February 26, 1999, Pamela’s diary.

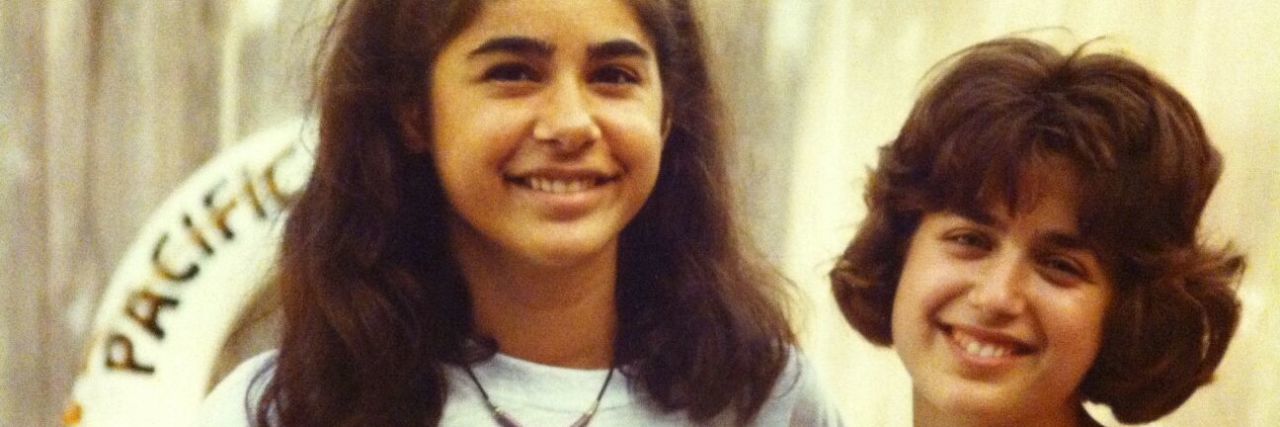

Funny thing is, I lived with my sister for 20 years before I knew she had any kind of artistic ability. We shared a bathroom, a bedroom and sometimes even clothes… I knew she could play volleyball, cook a delicious meal without following a recipe and was a fashionista… but I had no inkling she liked to do things with her hands.

I learned it after reading her diaries….

In 1998, Pamela experienced a major nervous breakdown while a junior at Loyola College in Baltimore, Maryland. She was initially diagnosed with major depression, but after several brief psychiatric hospitalizations, self-destructive behaviors emerged: addiction, self-mutilation and suicide attempts. The doctors changed her diagnosis to borderline personality disorder (BPD). It made more sense. Impulsivity, fear of abandonment, intense personal relationships and pervasive loneliness were long-held characteristics of Pamela’s personality.

They said what she needed was long-term treatment. She lived in a residential setting for 18 months in Massachusetts. It was in an art studio there that she discovered art therapy, journaling and poetry as a means of expression and healing.

Although it was hard for Pamela to tell me what was going on inside her mind, her art was a window that helped me see in. She was ashamed of having a mental illness and the stigma that went with it.

Sometimes, after driving over three hours to visit her, I’d find Pamela quiet — not knowing quite what to say when her life was not going well. But the art on her walls spoke volumes about her inner pain. It taught me more than any textbook about BPD.

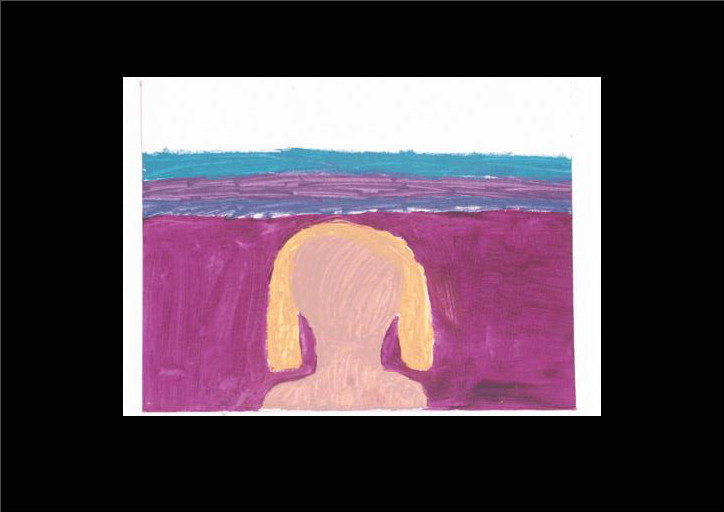

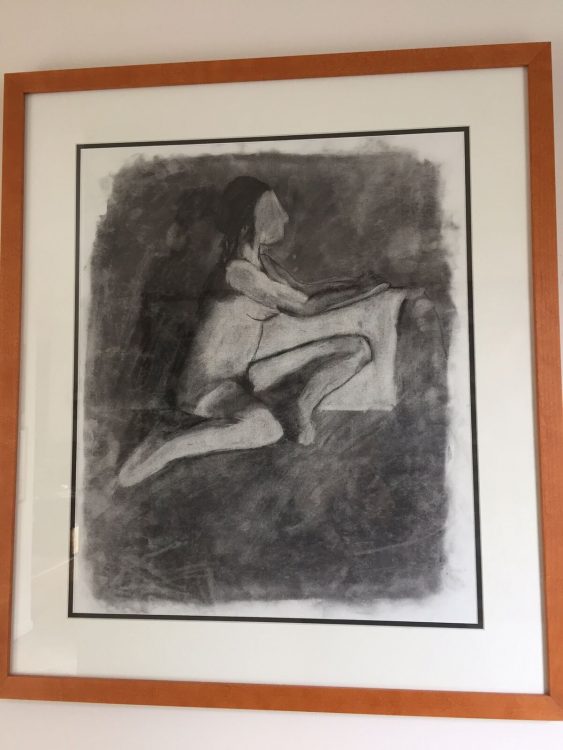

Pamela drew this self-portrait of a girl without a face. It looks nothing like her in real life. Pamela was dark-skinned brunette. One of the features of BPD is to not have a cohesive self-identity, and this piece helped me understand she was not just confused the way many teenagers are — she was truly tortured every day about who she was. She felt like as though she was drowning, just like the girl in the painting below.

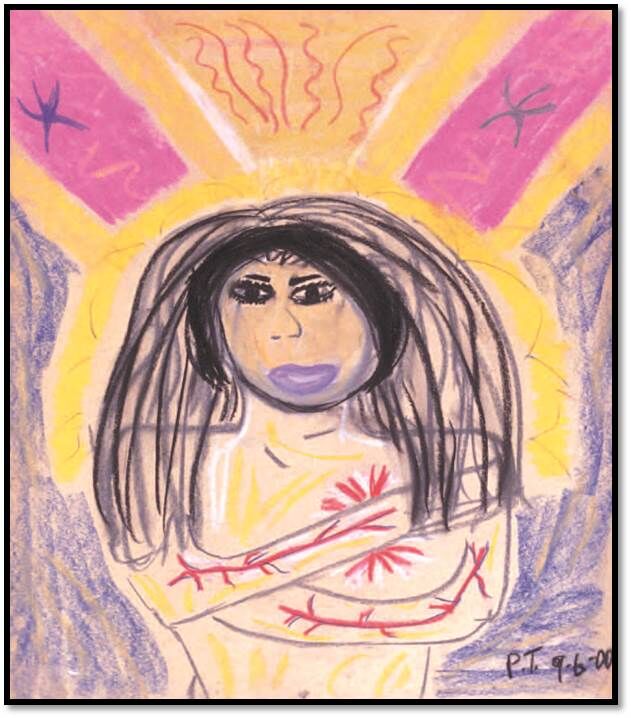

Pamela drew this image of a girl with cuts on her arms. On the inside, Pamela really hated herself and how hard it was to control her emotions and impulses.

BPD is a disorder of emotional processing, because the brains of those with BPD actually feel and process emotions differently than others. Individuals with BPD report experiencing emotions rapidly and intensely, which feels extremely painful.

Imagine having a migraine that is so intense it just doesn’t go away. The pressure is so bad that you are desperate to do anything that will bring you relief.

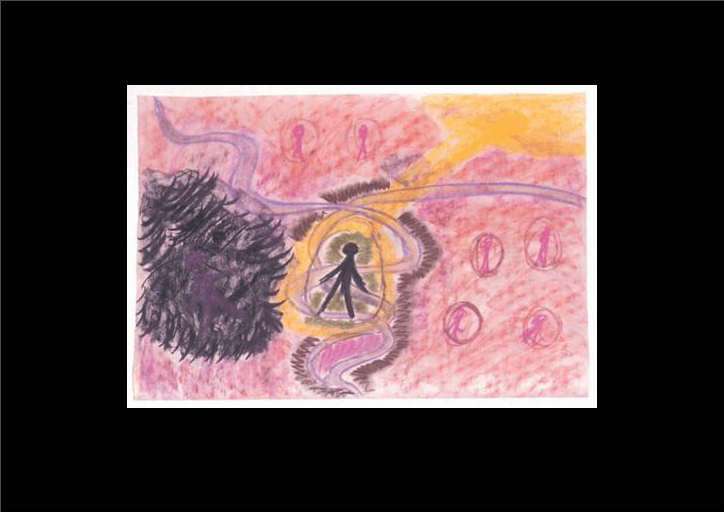

This is how Pamela felt when her BPD symptoms became overwhelming. Invariably, she resorted to self-harm behaviors to numb the pain – cutting, vomiting, addiction. She was not proud of it, but felt trapped and confused about which road to take as evidenced by the figure in this picture.

Once Pamela received therapy and achieved sobriety, she learned to cope with her shifting emotions in a healthy way by using her hands. Sketching, painting, pottery and scrapbooking all became sensory experiences which helped her self-soothe.

In fact, art not only helped Pamela feel good about herself, but it helped others see her as more than just a psychiatric patient with BPD. Beyond that label, what emerged was very smart, talented and creative young woman.

When I visited, Pamela would take my hand and show me her latest pieces. Walls which were once as sad and bare as she felt, were now splashed with color. Art became a source of pride for Pamela, and helped build her confidence. She could finally do something better than her older sister…

With ongoing talk therapy, Pamela eventually moved into an apartment, had a job and steady boyfriend and achieved stability. Her artwork became more steady and controlled, signaling her recovery. She could focus the world around her painting still lifes, landscapes and portraits rather than in inwardly toward her emotions and herself.

In the spring of 2001, the unthinkable happened. Her doctors in a residential treatment facility in California put her on a mood elevating drug that has certain food restrictions. Hard cheese was one of them. Although Pamela and her caregivers knew of these food restrictions, she was served pizza with cheese on it for lunch one day. Her blood pressure immediately spiked, causing a fatal bleed in her brain. Tragically, Pamela died three days later.

We found her diaries when we were collecting her belongings at the facility. Her words jumped out at us — in page after page of book after book. We were so happy to have the enduring legacy of her voice – and yet distraught with grief and longing for the person she was.

It seemed unfathomable that, after all her hard work toward recovery, Pamela died as a result of mismanaged mental health care, and lack of effective treatment for BPD.

In the days after the funeral, my mom and I carefully propped up all of Pamela’s artwork around her room. There was so much of it –— collages, scrapbooks, watercolors, pottery, painting, charcoals.

As the years went by, we framed some of the more traditional pieces and hung them in the halls of our home. We took digital pictures of her art, and had them made into note cards. We gave reproductions of Pamela’s art to her friends, and shared them with those in the mental health field, to help shed a new light on BPD.

Pamela’s art was a sign of her life, both of her internal struggle, but also of insight and creativity. She was living proof that individuals with BPD are smart, talented and creative. They are so much more than the clinical perception that has been perpetrated over the years that they are the “most difficult” psychiatric patients to treat.

While Pamela is no longer with us, her art endures in “Remnants of a Life on Paper: A Mother and Daughter’s Struggle with Borderline Personality Disorder” (Baroque Press, 2013), which my Mom and I wrote to tell share Pamela’s diaries and art with the world. We wanted to break the silence about BPD, so that Pamela’s life and the thousands who struggle just like her on a daily basis should not be defined by their disorder, but by the creativity of their minds.

Pamela’s artwork was featured among 35 other pieces created by those impacted by BPD, in “Empowered to Create,” an art show and auction held at Fountain House Gallery for Borderline Personality Disorder Awareness Month at 702 Ninth Avenue at 48th Street on Thursday, May 18, 2017.

Artwork via Pamela Tusiani