What the Netflix Series 'Workin' Moms' Got Wrong About Borderline Personality Disorder

Sometimes the news isn’t as straightforward as it’s made to seem. Renée Fabian, The Mighty’s features editor, explains what to keep in mind if you see this topic or similar stories in your newsfeed. This is The Mighty Takeaway.

Editor's Note

This post contains spoilers about season two of “Workin’ Moms.”

Season two of “Workin’ Moms” just dropped on Netflix in the U.S. on July 25. While many loved its relatable comedy, a short (and unnecessary) plot with a stalker-ish character set borderline personality disorder (BPD) up as a punchline that only furthered BPD stigma.

Originally a Canadian series, “Workin’ Moms” follows four mothers as they navigate the world balancing kids, home and work. One of the four main characters, Anne Carlson (Dani Kind), is a psychiatrist.

In the ninth episode of “Workin’ Moms” season two, she’s goaded into giving a guest lecture to a college class where she is approached by college student Carly. Carly tells Anne she’s a big fan and reads her thesis before inviting her out.

“Do you think I could take you for a coffee sometime?” Carly asks. “I would love to share a donut with you or just get inside your skin and be you. Just joking.”

Anne, clearly flattered, agrees to coffee and gives Carly her business card before she heads off. In the next episode, episode 10, Carly shows up at Anne’s office by unexpectedly booking an appointment under the name Cher, “like the singer,” Carly said.

“So listen, it was so great to meet you the other day and I know that we said we were going to go for coffee, but I just thought, why don’t I book a session and surprise you,” Carly says. “That way I can pick that enormous brain of yours while knowing that I’m compensating you for your time.”

Anne clarifies, “I’m sorry, so you want to pay to listen to me talk about myself for an hour?” Carly says yes, and Anne says, “I can get behind that.” At the end of the session, however, Anne refuses payment, so Carly offers to take her for lunch instead. Carly lets slip that she knows Anne’s daughter’s name thanks to Facebook (friend request pending). “We’re like obsessed with each other,” Carly tells Anne before leaving the office.

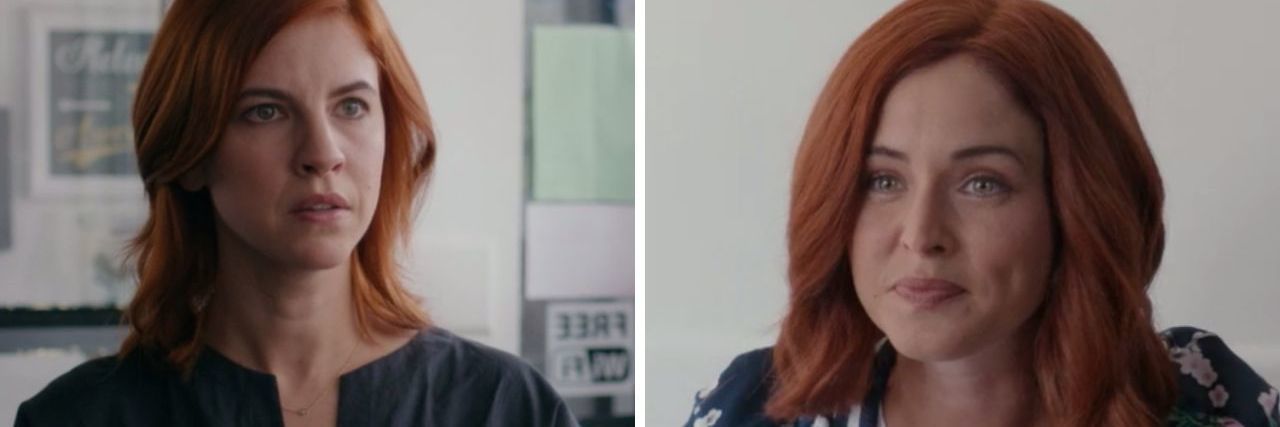

When we next see Carly, she slides into a seat across from Anne at a restaurant with her hair looking exactly like Anne’s red bob. “It’s like I’m your twin even though my hips are twice the width of yours,” Carly tells Anne. This time, Carly knows too much personal information that couldn’t be found on Facebook, and Anne calls Carly out, warning her to stay away from her and her family.

“Listen to me, you stay away from me and stay away from my family or I will tie you up and pluck every hair from your nose until you die of dehydration from the tears running down your cheeks,” Anne threatens. “By the way, you should really consider seeing a doctor. In the short time that I’ve known you, I’ve already diagnosed you with borderline personality disorder.”

Anne throwing a borderline personality disorder (BPD) diagnosis at Carly is a low blow. Many mental health professionals use BPD as a catch-all for patients they would rather write off as “stalkers,” “manipulative,” “hysterical” or “hopeless” as opposed to offer them competent treatment or basic empathy. This view has crept into our daily lives, which is a mischaracterization of what it’s like to have BPD.

BPD is characterized by nine hallmark symptoms, including fear of abandonment, difficulty regulating intense emotions and stormy relationships. Though it’s often misdiagnosed, the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) estimated between 1.6% and 5.9% of people in the U.S. live with BPD, 70% of whom are women. It’s the mental illness with the highest suicide rate — and, contrary to what you might hear, one of the most successfully treated mental health conditions.

Representation of mental illness in the media matters. Many studies show that negative images of mental health in the media, including film and TV, lead to increased mental health stigma, the belief people with mental illness can’t recover and a lower likelihood that people with mental health issues will seek treatment. For a stigmatized condition like BPD that doesn’t get significant representation at all, any damaging portrayal like in “Workin’ Moms” only makes things worse.

It’s also unclear why this tiny plot line was included in “Workin’ Moms,” and why the show creators decided it was necessary to (incorrectly) use a mental illness to explain Carly’s behavior in the first place — she could have just been labeled as weird or a stalker. There’s nothing wrong with having a BPD diagnosis, and Carly’s behavior does not represent most people’s experience with BPD at all.

“Last year, I received a new mental health diagnosis: borderline personality disorder (BPD),” wrote Mighty contributor Rebecca RH in her article, “Why My Borderline Personality Disorder Is Not Like the Stigma.” She continued:

What is it about BPD that makes me reluctant to share my experiences? I thought about it and realized it was the stigma — the negative perceptions of people with BPD being ‘manipulative’ or ‘dangerous.’ I didn’t want people to make negative assumptions about my experience or about who I was as a person. But the only way to challenge this stigma is to speak up against it, to provide alternative experiences and views and to try and show people what it can be like.

For more on living with BPD and why it’s not like the stigma, check out these other Mighty articles from our mental health community:

Header images via Netflix