It seems to me like the rest of the world is often more comfortable when they hear stories of rosy optimism and conquering disease. I figured that out early. I could post glowing optimistic stories of each new victory I overcame and I would receive endless praise. It was great, it fed my ego, but it wasn’t always honest.

When I was first diagnosed with inflammatory breast cancer (IBC), the cancer machine whirred into action, and I was surrounded by well-meaning and compassionate people who offered to do almost anything. For someone like me, who is very self-sufficient and independent, it was difficult for me to accept the help. But I did accept the help, and I am forever grateful for it.

Now that I am through the hard parts, most of the people have disappeared. Some people might be more comfortable knowing that I am healing and recovering. They might not want to hear about the days I can barely get out of bed because I am so tired from over-exerting myself, or about the difficulty I have reaching things on high shelves because my arm no longer has the range of motion it once had because of the missing lymph nodes. They might not want to hear about the struggle for breath when I am walking a block or two. They might not want to hear about the depression, or the anger, or the loneliness that inevitably creates a barrier between me and the rest of the world. They might not want to hear about the insomnia or the drug addiction that can develop because of the long drug use. And they really might not want to hear about the chance of reoccurrence or worse.

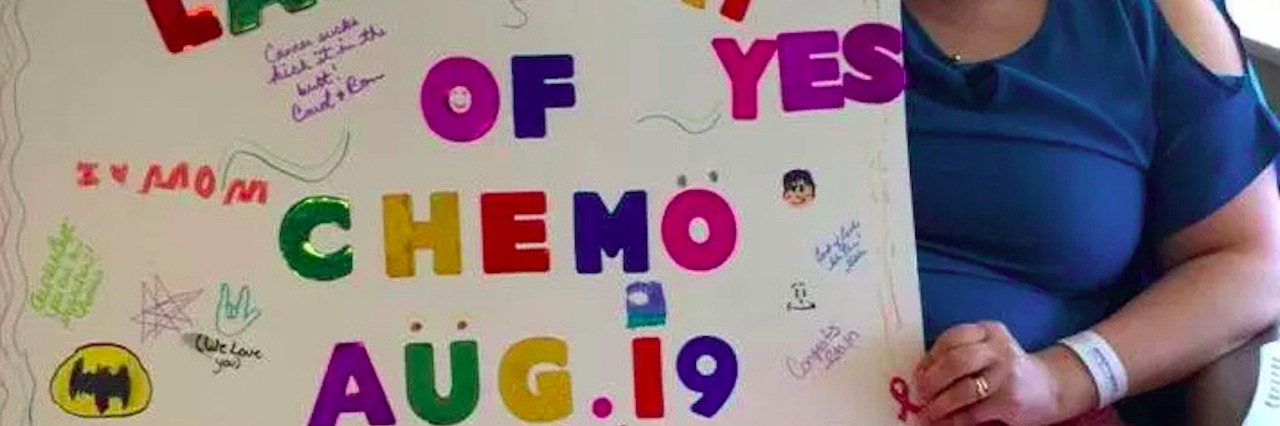

When the bell has been rung, it signals the end of chemotherapy or radiation. It doesn’t signal the end. That distinction needs to be made because in the minds of loved ones, it can sometimes signal relief for them. When a cancer diagnosis is given, it can feel like a death sentence, and so the sound of the bell can sometimes feel like reprieve. It’s not. For the cancer patient, the sound of the bell is merely a beginning of a new battle. It signals the beginning of reclaiming everything that was lost when cancer ripped the ground out from beneath them. It signals the beginning of fear — the fear when the other shoe will drop, when or where the next lesion or tumor would appear, the fear of having to go through all of this again, the fear of everyone disappearing just when the next phase of the battle is beginning. These fears are realistic and can be probable.

Through my own experience, there are nine things I have discovered that are the most effective ways of continually showing love and support for someone recovering from cancer.

1. Endure the loneliness and depression. Cancer survivor stories are not always depicted honestly. The positive ones that depict overcoming great odds might skip over the hard parts of struggle, frustration, isolation and depression. The most loving thing a person can do is endure that with the ones going through it. It can be a long road back.

2. If the cancer patient wants or needs to talk about their final days — their wants and desires in the event of a poor prognosis, their expectations and blessings for those left behind after they do die, or their funeral — let them.

3. Don’t just say, “I’m praying for you.” This is no way is meant to minimize the power of faith, or to imply that prayer is not warranted. But often times, this statement can be used as a means of offering comfort, and this might not always be comforting to that person. If you feel compelled to pray, then just pray. But as a means of offering comfort, more practical ways could be reaching out and asking how you can help.

4. Offer physical support or time. Cancer, as with many other major illness, can be incredibly isolating. The most effective means of offering support can be to spend time with the patient. Even just sitting in the same room saying nothing can be more powerful than all the flowery words in the world. Watching a movie, or rubbing their feet, or bringing tea and mindless conversation can be more powerful and meaningful to the cancer patient.

5. Don’t focus on the disease, but don’t gloss over it either. This one might seem like a paradox, but it’s not. Cancer can take so much from the lives of those it infects, but it shouldn’t rob a person of their identity. Where someone used to be a prolific writer, or musician, or cook, or [insert interest here] — they are still that person. But to try to forget that a person’s life was irrevocably changed by such a powerful disease is to minimize their struggle.

6. Don’t expect there to be a time limit to their grief. Telling a cancer patient to just stay positive, or to have faith, or to focus on being grateful might make the rest of the world comfortable, but not necessarily the cancer patient. If the patient is angry, let them feel that anger. The stages of grief don’t have a formulaic time frame, and it is unfair to expect that from anyone. Cancer robs so much, not just time. Though the obvious struggle might be over, the loss can sometimes have a rippling effect. A limb or a body part might have been removed, chemotherapy might have caused infertility or put a woman into early menopause, there could be a loss of cognitive functioning as a result of “chemo brain,” there could be significant weight loss or gain, there could be a loss of muscle function, there could be a loss of sexual intimacy or function, and there could be a loss of identity. These things continue to cause no end of anger, depression or sadness. It could cause the breakdown of a marriage due to stress and conflict. It could mean the loss of dreams and expectations for the future. Cancer patients find that sometimes they lose friends because of cancer. The most loving thing someone can do is allow the cancer patient to feel those things.

7. Continue to offer help. Cancer patients can often take up to a year or longer to recover after their final treatment. Fatigue is a huge symptom that is hard to overcome. Fatigue is more than just feeling tired. It is an absolute feeling of moving through quicksand. It is mental, physical, and emotional exhaustion. Cutting the lawn, doing a load of laundry, shoveling a driveway, going grocery shopping, or cooking dinner can sometimes take every ounce of energy from a recovering cancer patient. There are good days, and that feels like a huge victory to them, but they are often short-lived. A recovering cancer patient might skip over these basic chores other people might take for granted in favor of sleeping on the sofa watching re-runs of “Friends.”

8. Don’t minimize or ignore their fears. No one wants to admit that a loved one could face this disease again, but those fears are realistic. It would be more productive to re-direct those fears. Help them face those fears. Let them know you will be with them every step of the way, and help them develop a contingency plan in the event that the cancer does return. Knowing that they have someone to face this disease with should it return is instrumental in moving beyond it and living for today.

9. Don’t disappear. This is often the most hurtful aspect of dealing with cancer. Life does continue to move on even though the cancer patient might feel like they are living in limbo. Making a conscious effort to remain present can be the single most important thing a loved one does. The cancer patient might feel like they have been a drain on the ones around them. They are not oblivious to the extra effort that has been put forth by those around them to help support them during the chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery. There may come a point where they will stop asking out of guilt or a feeling of becoming a burden, but they absolutely do still need their friends and family around them.

A version of this story originally appeared on Conceived.

We want to hear your story. Become a Mighty contributor here.