What It Was Like to Fight for School Inclusion in the 1970s

Editor's Note

This story contains terms to describe disability which are considered to be outdated and/or offensive today. They are presented here in their historical context to highlight the systemic discrimination faced by children with disabilities attending public schools in the 1970s.

In 1972, a U.S. Congressional investigation led by the Bureau of Education for the Handicapped found that the country had 8 million children requiring special education services. Of this total, less than half — 3.9 million students — received an adequate education. The research revealed that 1.75 million children with disabilities were receiving no education. Another 200,000 were institutionalized. An additional 2.5 million were receiving a substandard education.

In 1973, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act was signed into law: “No otherwise qualified handicapped individual in the United States shall, solely on the basis of his handicap, be excluded from the participation, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.”

Section 504 is known as the United States’ first federal civil rights protection for people with disabilities. Its language built upon previous civil rights laws that protected women and minorities. It recognized that society has historically treated people with disabilities as second-class citizens based on deeply held fears and stereotypes held for over a century. In essence, the law stated that no program receiving federal funds could discriminate against a person with a disability.

In 1975, Congress passed the Education for All Handicapped Children Act with the goal of remedying the serious educational inequalities represented by the ’72 Congressional investigation. The central principle of the act mandated that all states receiving federal education funding must create a “policy that assures all handicapped children the right to a free appropriate public education.” In addition, the act stipulated that all such students must undergo an individual evaluation leading to an Individualized Education Program (IEP) designed to create a personalized plan to best fit the educational needs of each student. The act required they be integrated into regular classrooms to the greatest degree possible, while placed in the least restrictive environment and granted access to services they would need.

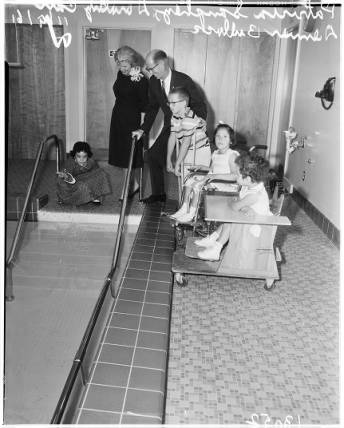

Oblivious to the laws and social movements, in June of ’72, I was a 7-year-old girl completing my fifth year as a Harlan Shoemaker student. My educational career had started when I was 2 years old, when I was diagnosed with cerebral palsy. Located in San Pedro, California, Harlan Shoemaker was the “Special Education School for the Handicapped” in Los Angeles County, providing therapies (now known as Early Intervention) as well as academic instruction to “special students” from Pre-K through 12th grade.

The previous year, I was a first-grader who often sat in a circle with classmates learning to read with “Dick and Jane.” Always eager to please my teacher Mrs. Jackson, my hand was often raised to read aloud. “See Spot run.” One seemingly routine day, Mrs. Jackson called the teacher over who taught in the classroom across the hall to look at my work. My teacher gave her the “Two, Too, and To” assignment I had just completed. They huddled in the corner for a few minutes, whispering so as to not disturb the students who continued on with the task. They called me into the hallway. Mrs. Jackson asked how I finished the 10-question assignment in 30 seconds. Uh oh… I’m in trouble. How do they know I didn’t read the questions?

The teachers towered over me. I stood between them and worried that my decision to rush through the assignment was not going to turn out well.

“We would like to know how you completed this assignment.” Mrs. Jackson asked.

I explained that there were two sizes of “fill-in” blanks. In the larger blanks, I wrote “Two” if numbers were in the question. If no numbers were in the question, I wrote “too.” Then for the smaller blanks, I wrote “to” since it was the only small word. Since I hadn’t read the questions, I braced to hear that all my answers were incorrect.

My eyes darted towards the brown carpeted floor as I feared my teacher’s next words.“Jennifer. Your answers are all correct.” Mrs. Jackson said with an eager smile. “We wanted to know how you did it!”

Whew… that was a close one!

The following week, my promotion to second grade had commenced.

Mom received a call from my physical therapist later in the week. She informed Mom of a search in progress. A search for two children who might benefit from an experimental surgery. They wanted one boy and one girl, children who displayed academic promise.

Mom and Dad discussed the opportunity with me while trying to explain “experimental.” They asked if I wanted the surgery.“Yes!” I squealed without hesitation.

Surgery and hospital costs came to tens of thousands of dollars, a bill that would have been impossible for my family to pay. I will forever be grateful to the Los Angeles Crippled Children’s Society and all of the other donors. Our family’s expenses totaled $150.

The surgeon operated on the left hip first. CP had impacted my left side more than the right. I spent eight weeks imprisoned in a heavy body cast that started above my belly button, extending down to my toes. I could not move without help — not even scoot. An embarrassing bedpan tended by Mom or Dad became my bathroom. A year and a half passed before the next surgery. Not eager the morning of the operation, I rubbed my unblemished thigh. Soon there would be a pink puffy foot-long incision to match the left thigh. I fought tears with all my might.

In the autumn of 1973, I completed rehab for the second time. Both surgeries were successful. I no longer walked on tiptoes with my arms held in the air for balance. The walk often mocked as “Frankenstein” by my able-bodied peers retired to a noticeable gait. A few months had passed when my yearly physical with the school district’s physician was scheduled with Dr. Morris. “Jennifer has surpassed all of our expectations.” She told Mom. “With the surgeries’ success along with her improved speech from years of therapy, she’s ready to be ‘mainstreamed’ into regular school.” “You really think so?” Mom wiped away her tears.

“Remaining at Shoemaker will just hold her back.” “Can I… Mom? P’ease!” My excitement grew.

“It will be a political move on my part advocating for Jen to leave this school to attend regular public school.” Dr. Morris continued. “The process may take over a year before being given consideration.”

She encouraged my family to consider this possibility before she took the risk. “I am planning to leave the school district. I will stay another year to help Jen if you decide to pursue the transition.”

When Mom and Dad asked if I wanted to go to regular school, “Are you kiddin’?” spewed from my mouth. “I alway’ wanted to go to Broad Avenue. It’s right down the st’eet.”

“Kids will laugh at you.” Dad warned. “Can you handle that?” “Ye’, yes. I can hand’ it.”

“You need to be sure. You need to be tough.”

Dr. Morris advocated for a year before my chance materialized. Both schools voiced concern. One did not want to release me because of state monies. The other did not want to accept me out of fear that my attendance would create confusion for their students. The challenges mounted with time. The overarching concern that appeared to crush all hopes came with a label.

An assessment conducted by a school district’s psychologist, a pre-requisite for transition consideration anointed me with a classification that baffled everyone. I had seen the school psychologist in the hallways over the years but had never met her. During our meetings, she asked questions from several booklets. I completed many short tests over the next few days. Some were simple. Other tests included timed puzzles that I did not complete in part due to an annoying white, big-dialed timer that stood at the table’s edge. My spasticity increased with each second’s tick.

The psychologist submitted her findings in a long-awaited assessment report to “The Powers That Be.” Individuals working for the Los Angeles School District who had not — and never would meet me — determined my future life’s direction. The school psychologist’s assessment report read, “I.Q. fell within “Retardation Range.”

“Retardation.” The one label I had fought against with all my might since I could remember. My world shattered. A doctor believes I’m “retarded.” How could this be? Mom and I attended an impromptu school meeting.

To my surprise, every teacher who had taught me since pre-school, speech and physical therapists who provided me with life-altering exercises for more than half a decade and Dr. Morris sat around a large circular table as Mom and I walked into the meeting. Their support brought me to tears. The emotion caught me by surprise and attempts to contain it only magnified my body’s uncontrolled twists. My face flushed with embarrassment.

“We all know how capable and smart this little girl is.” The doctor stated. “We need to explain Jen’s timed-test findings found in Dr. Slater’s assessment.”I sat quietly as I listened to the educators and health care providers around the table. Mom sat silent except for her occasional head nod in agreement accompanied with “Yes” or “um-hum.”

“OK, then.” Dr. Morris summarized prior to the meeting’s end. “Each one of us will write a letter to support Jen’s transition. Send the letters to my office and I will submit a packet to the school district.” In the summer of ’74 I was granted a “trial run.” Broad Avenue was the nearest public elementary school, and the school I had dreamt of attending since forever. Classmate’s snickers challenged my ability to hide any resemblance of sadness or frustration. Aware that my behavior was under scrutiny equally to – if not more than grades earned – I swallowed my emotions. I must pass their test. In the fall of ’74 I became Broad Avenue’s newest fifth grader. The promotion from first grade was erased. My peeved pride paled to the excitement of attending the school across the street from home. My admittance into regular school came just months before the Education of All Handicapped Children Act of 1975.

I attended Broad Avenue and other schools throughout high school graduation without an IEP or academic accommodations. The challenges were many, from a teacher who graded me down one letter grade on each assignment/exam for “poor penmanship” to often running out of time on essay exams. I felt pressure to “ace” whatever portion I was able to complete on exams to maintain an acceptable high school GPA for college admittance. I experienced teasing and ridicule from new classmates at the start of every school year. I felt compelled to explain “me” with every new person who entered my life. I felt a continued urgency to prove I belonged.

In general, students with disabilities attending “regular school” after 1975 have done so according to the Education for All Handicapped Children Act. With best intentions for equal access to education, students were often placed into segregated and far removed classrooms such as in trailers on the perimeter of K-12 public schools with less-than-rigorous curricula. In 1990, the Act was reauthorized and renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). The evolution for inclusion of students with disabilities within public schools continues today.

Photos via University of Southern California.