Nervously, Denise sat in a chair staring into her doctor’s face. Would she finally get the answers she had been hoping for throughout her whole life? “Clearly this is rheumatism!” the physician explained to Denise, who had been living with chronic pain since she was a child. The German woman and former nurse knew the diagnosis was wrong — it just did not match her lifelong symptoms — but who would believe her? For many years doctors had been telling her that she was only imagining the pain, that it was all in her head. At least this time Denise’s physician believed her.

Denise was prescribed strong drugs to treat pain caused by rheumatism. Her pain did not go down; instead, Denise developed severe psychosis. It took 12 months to figure out those were side effects of the medication for a condition she never had. Over the following years, many MRI scans and other diagnostic tests were performed — all without clear results.

One hot summer night her condition acutely deteriorated and she had to call an ambulance. When the emergency personnel arrived, they noticed that Denise’s body was covered in bruises — another sign of her true medical condition. Denise was used to all kinds of blue and green colors garnishing her body and could have never imagined what happened next. The medical team accused her husband of abusing her.

Now, this was enough. After she had convinced the ambulance staff she was not being abused by her husband, she decided to restart her search for the right diagnosis. Twelve years and 25 doctors later, she finally found out the true cause of her condition: Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a rare, genetic illness which she was born with. Today the 47-year-old says she has lost trust in medical professionals and fears every appointment.

Research suggests that over 10 percent of all diagnoses are wrong [1]. This means if there are 10 people in a waiting room, at least one of them will be labeled with a wrong condition. Diagnostic errors [2] is the umbrella term that includes misdiagnoses, diagnoses that are missed altogether, wrong, or could have been made much earlier. The National Academy of Medicine in the United States concluded it is likely that every person will experience such an error at least once during their life [3]. Even though misdiagnoses seem to be a real threat to public health, insight is limited. While in the U.S. alone as many as 12 million people might become the subject of a diagnostic error each year [4], they are rarely documented.

The vast majority of these are inconsequential, but given the tens of millions of diagnoses made every year, the tiny fraction that does involve harm translates into a very large aggregate number of patients harmed. In 10 percent of all patients’ deaths, an underlying diagnostic error was discovered as an additional factor [5], and it is estimated that 200,000 Americans die because of medical errors each year [6]. This equals the whole population of Salt Lake City. Another study suggests that from the 850,000 people that die in US hospitals each year, a diagnostic error contributed in at least 8 percent of deaths. Half of them could have survived with the right diagnosis [7]. However, the true extent of this problem is so hard to measure that nobody knows how high the real number is of people who have died because of misdiagnoses on a global scale.

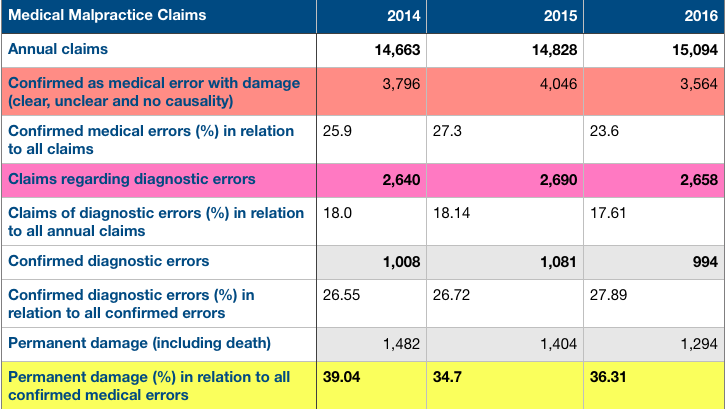

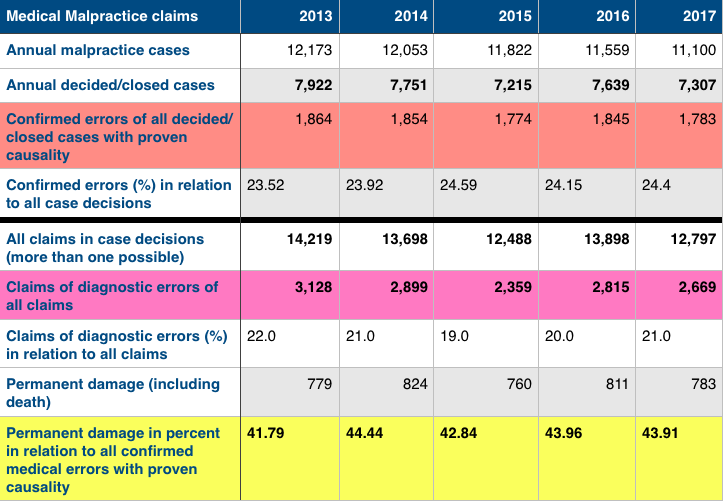

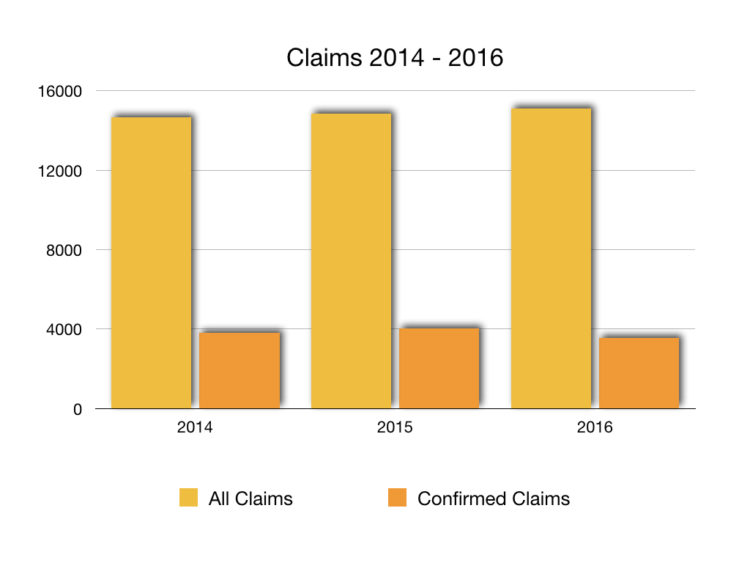

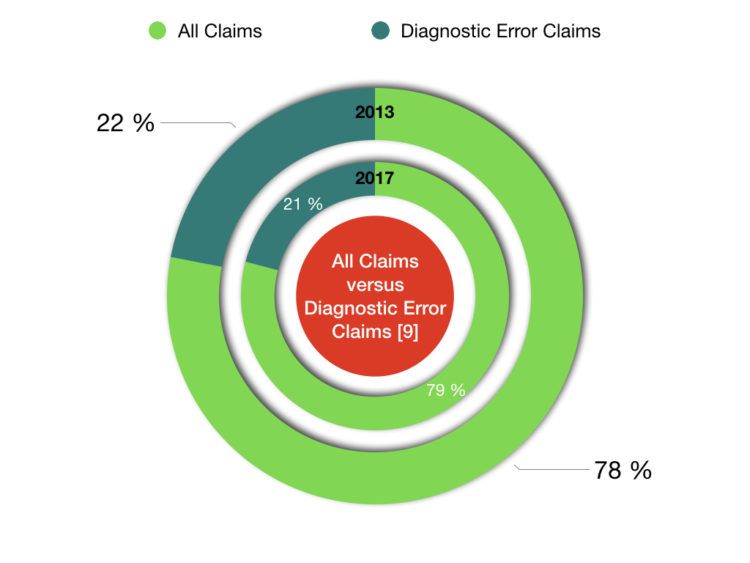

In Germany, two different entities collect data about medical malpractice claims; no governmental authority oversees medical errors. Based on their data, medical errors have not changed much over the last years. And diagnostic errors are still the second leading cause of those claims in both statistics. Between 18 and 22 percent of all claims were filed regarding diagnostic errors. And 34 to 44 percent of all confirmed medical errors led to permanent disability or death.

Analyzing these malpractice statistics is not an entirely reliable way to figure out the real number of diagnostic errors since over 55 percent of victims do not report mistakes to anyone [10]; and if they do, they might not proceed to sue. Less than 3 percent of malpractice victims go to court.

Interestingly, the UK reports around the same amount of claims as Germany. For example, in 2010/11, 13,001 claims were reported, with a peak in 2013/2014 with 16,747, and back to 14,768 in 2016/2017 [11].

Looking at Denise’s experience, one might assume patients with rare illnesses would be affected by misdiagnoses more commonly. Patients with rare conditions are certainly at risk, but surprisingly, the majority of diagnostic errors involve common conditions. A research study conducted by Dr. Gordon Schiff, a physician and patient safety advocate at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, found conditions such as lung embolism, reactions to medication, lung cancer, gastrointestinal cancer, breast cancer, stroke and many other common conditions are often not diagnosed correctly [12].

Josef was admitted to a hospital in Germany due to severe back pain and respiratory distress. One quickly-done x-ray and the doctor was certain: Josef had to have pneumonia. After five days of high dose antibiotics administered through his veins, his condition hadn’t changed. Despite this, the hospital decided to discharge him. His primary care physician remained skeptical. There were too many pieces that did not fit the diagnosis of pneumonia. Josef was ordered to have a CT-scan right away. Only seconds after the test began, people stormed into the room carrying a heart defibrillation device. Blood clots had formed everywhere in Josef’s lungs, a condition called lung embolism. The emergency crew immediately started the life-saving therapy, and he survived.

Misdiagnoses may have severe consequences. A study conducted by Dr. Schiff, in which doctors reported errors they had been involved with, showed one-third of all misdiagnosed patients suffered life-threatening and deadly outcomes, or permanent disability [12], and more than 40 percent endure moderate damage. Naturally, physicians would remember the most significant errors with the most harm the best. But still, the consequences can be unbearable for the patient.

As a matter of fact, misdiagnosed lung embolism, as in Josef’s case, was identified in many autopsies as a so-called class I diagnostic error [13]. These errors are defined by a major discrepancy of diagnosis, and ”knowledge before death would have led to a different management that could have prolonged survival or cured the patient [13].” Interestingly, in a study investigating patient safety in developing countries, 44 percent of patients that experienced adverse events suffered permanent disability or death [14]. The number does not differ too much from what Dr. Schiff has reported for the U.S. Josef was lucky. He only suffered a shock, and not permanent injury or death.

Imagine every misdiagnosis as the leading piece in a row of dominoes. When the first one falls, a myriad of other pieces start to collapse. Just a single misdiagnosis can lead to a lifetime of suffering the consequences – not only physically, but also mentally and financially [4].

Furthermore, diagnostic errors affect national economies as well. Medical errors cost the United States $19.5 billion in 2008 [6]. Ken Perez, vice president of healthcare policy, Omnicell, Inc., estimated a total cost of $20.8 billion [15] in 2016 based on population growth, but if one applies quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) to the 250,000 who die each year from medical errors, the loss of QALY’s for those deaths is $187.5 billion to $250 billion.

Wrongfully used diagnostic tests alone might cost $25 billion each year [16]. With $25 billion, the US could feed 2,437,835 families of four for one year [17].

At the same time, health-related costs are rising. ”For example, misdiagnosis caused by false-positive mammograms alone cost the U.S. four billion dollars annually,” Ken Perez said.

Diagnostic errors have consequences for many areas of health economics. For instance, one-third of all malpractice suits in the U.S. are due to diagnostic errors [18]. Similar numbers have been shown in the table above for German malpractice claims. However, no other country beats the U.S. in terms of out-payment for won claims, which is one reason why physicians practice defensive medicine in the U.S., and therefore tend to overuse specific tests in order to protect themselves from becoming the subject of an expensive lawsuit. According to Perez, another reason for the excessive use of diagnostic tests might merely be accessibility to equipment, such as MRI machines and CT scans — “We have them, so we use them. And when you don’t have a definite diagnosis, you use other approaches.”

On the other hand, some tests are underused to save money. Both scenarios can cause misdiagnosis and harm to the patient. And it seems to be hard to find the balance. ”We cannot just do more tests to reduce misdiagnosis. The premise here is that we have to test sufficiently,” Perez said. ”For example, let’s look at CT scans versus standard x-ray or ultrasound: A CT provides greater insight of what a patient might have, but it is also more costly. And then there is a human cost as well, because each CT scan increases the risk of cancer materially.” When it comes to diagnostic errors, there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

Rana experienced the worst-case scenario. Following the misinterpretation by a few doctors, Rana experienced every mother’s nightmare. On a warm summer day in Dallas, Texas, Rana, a nurse herself, discovered that one of her 4-week-old twin daughters wasn’t moving her leg anymore. Worried, she rushed to the emergency room. Some x-rays later, her daughter was diagnosed with fractures, which led them to examine the twin sister as well. Both 4-week-olds were found to have blurry edges on the end of their bones. Suddenly, her children were removed from her care, and Rana was confronted with an accusation of child abuse. On top of this, the authorities took Rana’s 3-year-old daughter out of her care as well, and delivered the devastated children to their grandparents on the same day.

Only after five months, the mysterious fractures an expert had found in both infants turned out to be caused by a genetic defect: Ehlers-Danlos syndrome in combination with vitamin D deficiency. Although the family was acquitted of all allegations and reunited, it took two more years and uncountable expert witnesses to fully prove their innocence. “We felt desperate and the worst kind of grief, apart from what we would have felt if they had died,“ Rana said of the consequences those events had on her family. “Even six years later, we suffer PTSD whenever we have a child get hurt.”

According to EURORDIS, an organization for rare disease patients in Europe, Rana’s experience is quite common for parents of children with rare diseases [19]. As a consequence of this experience, she developed post-traumatic stress disorder and will never get back the months she missed being with her children.

It is apparent that misdiagnoses are a worldwide problem, but why do all those errors occur and how can we prevent them?

This question plagues scientists worldwide because there is no single common factor. According to Dr. Mark L. Graber, founder of the Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine, a misdiagnosis is typically caused by some combination of system or cognitive errors [20]. Dr. Graber said that common system errors include such things as breakdowns in communication or care coordination, not having experts available when you need them, lost test results or unavailable medical records at the time of the visit. Cognitive mistakes, on the other hand, might be caused by a lack of time to make a differential diagnosis, as well as antipathy for a patient resulting in the doctor giving less attention to their diagnosis.

”Not having enough time during the clinic visit” is thought to be one of the most pressing issues that leads to errors, Dr. Graber said. And most of the time it is a combination of several factors. But is this true on a global scale? Based on one study, developing countries do not experience much more misdiagnosis than the US [14] or Germany. It seems that the problem persists in completely different health systems.

An autopsy study did also not show any larger differences between hospital-related misdiagnosis and deaths in different countries, although the fluctuation between two areas in one and the same country was rather large [7]. While the South Lothian District hospital in Scotland, for example, reported a 38 percent rate of significant errors between 1975 and 1977, the University of Edinburgh only stated a 15 percent rate during 1978. However, South Lothian District hospital carried out ten times the amount of autopsies and is therefore much more likely to report a higher number of errors.

There is a growing movement internationally towards transparency when errors occur, including the goal of disclosing errors to the patients involved truthfully and in a timely fashion. Nonetheless, given the constant fear of malpractice suits, not to mention the desire to avoid blame and shame, many physicians are reluctant to disclose or report diagnostic errors they become aware of. But would physicians deliberately cover up their errors? In 2016, 7 percent stated they would hide a mistake that could harm the patient, and 14 percent answered with ”it depends.” If their mistake would not harm the patient, 19 percent would cover it up, and 22 percent think it depends on the circumstances, based on a Medscape report in 2014 [21].

An interesting approach to counteract this development was proposed by the Massachusetts Medical Society. They suggested a so-called “Disclosure, Apology, and Offer” system that would completely revolutionize defensive medicine. This policy encourages physicians to advocate for their patients, and fully disclose mistakes. While the patient would immediately be compensated for the error, the physician, on the other hand, would not have to fear legal consequences [22].

Receiving a wrong diagnosis can never be entirely avoided, but the patient is still not defenseless. The Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine [23] suggests a solution is to ”raise awareness of diagnostic error and its importance among physicians, the public, healthcare organizations and funding sources.” This among other measures could help to prevent patients from future misdiagnoses.

In Denise’s opinion: ”Patients should question the doctors’ statement and not just believe them. Also, they should stay persistent and not get intimidated by physicians.” The World Health Organization agrees. However, actively participating in one’s healthcare is especially tricky for patients. Many physicians in industrialized countries don’t feel comfortable being doubted by their patients; they are high up in the hierarchy, whereas the patient is very much at the bottom [2]. The National Academy of Medicine report strongly suggested the diagnosis should be a team effort, not just the job of the doctor, but generally, it is not.

Although patient empowerment is on the agenda for patient safety organizations, the question remains: Is this realistic? No, not at this point. In fact, evidence indicates that many medical doctors are not aware that they could even make a diagnostic error. They acknowledge the existence of misdiagnosis but doubt they would be the one to cause it [24]. As long as this mindset doesn’t change, diagnostic errors might not go down much in the future. “Awareness is growing, but the vast majority of doctors, hospitals, and patients remain unaware of the problem, or they are aware but haven’t taken steps to address the problem,” Dr. Graber explained.

The first step in reducing diagnostic errors is being able to measure them in the first place. “It is difficult, at best, to actually measure the rate of diagnostic errors. The hospital that reports the most errors is probably the one that is the best at measurement, and may well have the best care. Hospitals that don’t care that much about safety don’t bother to measure, and so they appear to have very few errors,” Dr. Graber said. But how can we actually measure diagnostic errors? ”We need more reproducible, standardized ways of defining errors and counting them. For diagnostic errors, the best approach would be to just ask the patient if the diagnosis was correct, and was timely. Or ask doctors – they know diagnostic errors as well. The current approaches hospitals use to measure safety breakdowns don’t typically capture diagnostic errors, and for all practical purposes, there is almost no safety measurement at all in clinics,” Graber said.

Perez is more in favor of using analytics to look at the outcome of treatment. He also believes that second opinions are an important tool for patients to protect themselves from misdiagnoses. ”You have to be aware of who you choose for a second opinion. It should be a doctor that does not have a vested interest and who has expertise in the area,” Perez said.

Autopsies are another helpful tool to identify diagnostic errors, and represent the ”gold standard.” Unfortunately, since the 1970s, autopsy rates have steadily declined in the US. An autopsy is still performed in less than 5 percent of all hospital deaths [25]. Worldwide we can observe a similar trend which means we are not detecting possible diagnostic errors through this approach anymore [25] — at least not in patients that died because of them. In the UK, autopsies are only performed in less than 1 percent of all hospital-related deaths [26]. Researchers find that in a large fraction of autopsy cases, 10 to 40 percent depending on how discrepancies are defined, the post-mortem diagnosis differed widely from the diagnosis made while the patient was still alive. This clearly stresses the importance of autopsies as a measure to save lives by attempting to learn from cases of diagnostic errors [13].

Diagnostic errors can affect people of any age and gender, and becoming a victim of at least one misdiagnosis in life is much more likely than getting hit by a car. Denise, Josef, Rana and so many other people survived diagnostic errors because they actively participated in their healthcare. They questioned their doctor’s, fought to receive a correct diagnosis and finally succeeded. However, they will never forget the times they were misdiagnosed, and they all suffered the consequences. Every victim deserves those errors to be addressed as such; every person that has not been misdiagnosed so far needs to be protected.

The first and most important step in reducing misdiagnoses is to acknowledge that they exist and to actively take responsibility for them, which means finding adequate ways to measure them. Patients need to be involved and engaged in their own healthcare. Never be afraid to ask: ”What else could this be?” Moreover, physicians need to change their mindset and let patients take an active part in the discovery of their diagnosis — as William Osler said, “Listen to the patient, and they will tell you their diagnosis.” Otherwise, we won’t stop this epidemic in the future.

Sources:

[1] Graber, M.L., Wachter, R.M. and Cassel, C.K., 2012. Bringing diagnosis into the quality and safety equations. Jama, 308(12), pp.1211-1212.

[2] WHO, 2016. Diagnostic Errors, Technical Series on Safer Primary Care, Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/252410/9789241511636-eng.pdf;jsessionid=0E11F88465DAF6BD6222DDA00FE6CAAB?sequence=1 [Accessed on May 30, 2018]

[3] Singh, H., Meyer, A.N. and Thomas, E.J., 2014. The frequency of diagnostic errors in outpatient care: estimations from three large observational studies involving US adult populations. BMJ Qual Saf, pp.bmjqs-2013.

[4] Pinnacle Care. The Human Cost and Financial Impact of Misdiagnosis, 2016, Available from: https://www.pinnaclecare.com/download/Human-Cost-Financial-Impact-Whitepaper.pdf [Accessed on May 30, 2018]

[5] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016. Improving diagnosis in health care. National Academies Press.

[6] Andel, C., Davidow, S.L., Hollander, M. and Moreno, D.A., 2012. The economics of health care quality and medical errors. Journal of health care finance, 39(1), p.39.

[7] Shojania, K.G., Burton, E.C., McDonald, K.M. and Goldman, L., 2003. Changes in rates of autopsy-detected diagnostic errors over time: a systematic review. Jama, 289(21), pp.2849-2856.

[8] Medizinischer Dienst des Spitzenverbandes Bund der Krankenkassen, Behandlungsfehler Jahresstatistik 2014 – 2016. Available from: https://www.mds-ev.de/richtlinien-publikationen/behandlungsfehler.html [Accessed May 30, 2018]

[9] Bundesärztekammer. Statistische Erhebung der Gutachterkommissionen und Schlichtungsstellen für die Statistikjahre 2013 – 2017. Available from: http://www.bundesaerztekammer.de/patienten/gutachterkommissionen-schlichtungsstellen/behandlungsfehler-statistik/ [Accessed May 30, 2018]

[10] Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2017, Americans’ Experiences with Medical Errors and Views on Patient Safety. Available from: http://www.ihi.org/about/news/Documents/IHI_NPSF_Patient_Safety_Survey_Fact_Sheets_2017.pdf [Accessed May 30, 2018]

[11] NHS, 2017. Annual report and accounts. NHS Resolution. Available from: https://resolution.nhs.uk/annual-report-and-accounts-201617/ [Accessed May 30, 2018]

[12] Schiff, G.D., Hasan, O., Kim, S., Abrams, R., Cosby, K., Lambert, B.L., Elstein, A.S., Hasler, S., Kabongo, M.L., Krosnjar, N. and Odwazny, R., 2009. Diagnostic error in medicine: analysis of 583 physician-reported errors. Archives of internal medicine, 169(20), pp.1881-1887.

[13] Aalten, C.M., Samson, M.M. and Jansen, P.A., 2006. Diagnostic errors; the need to have autopsies. Neth J Med, 64(6), pp.186-90.

[14] Wilson, R.M., Michel, P., Olsen, S., Gibberd, R.W., Vincent, C., El-Assady, R., Rasslan, O., Qsous, S., Macharia, W.M., Sahel, A. and Whittaker, S., 2012. Patient safety in developing countries: retrospective estimation of scale and nature of harm to patients in hospital. Bmj, 344, p.e832.

[15] Perez, K., 2016. The Human and Economic Costs of Medical Errors, HFM Blog, Available from: https://www.hfma.org/Content.aspx?id=48695 [Accessed on May 30, 2018]

[16] Newman-Toker, D.E., McDonald, K.M. and Meltzer, D.O., 2013. How much diagnostic safety can we afford, and how should we decide? A health economics perspective. BMJ Qual Saf, 22(Suppl 2), pp.ii11-ii20.

[17] United States Department of Agriculture, 2014. Official USDA Food Plans: Cost of Food at Homa at Four Levels. Available from: https://www.cnpp.usda.gov/sites/default/files/usda_food_plans_cost_of_food/CostofFoodJul2014.pdf [Accessed May 30, 2018]

[18] Tehrani, A.S.S., Lee, H., Mathews, S.C., Shore, A., Makary, M.A., Pronovost, P.J. and Newman-Toker, D.E., 2013. 25-Year summary of US malpractice claims for diagnostic errors 1986–2010: an analysis from the National Practitioner Data Bank. BMJ Qual Saf, 22(8), pp.672-680.

[19] EURORDIS, 2014. The Voice of 12,000 patients. Experiences and Expectations of Rare Disease Patients on diagnosis and Care in Europe. Available from: https://www.eurordis.org/IMG/pdf/voice_12000_patients/EURORDISCARE_FULLBOOKr.pdf [Accessed May 30, 2018]

[20] Graber, M.L., Franklin, N. and Gordon, R., 2005. Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Archives of internal medicine, 165(13), pp.1493-1499.

[21] Kane, L., 2014. Medscape Ethics Report 2014: Money, Romance and Patients. Medscape. Available from: https://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/public/ethics2014-part2 [Accessed May, 30 2018]

[22] Beaulieu, D., 2012. Disclosure, Apology, and Offer: A New Approach to Medical Liability. Massachusetts Medical Society. Available from: http://www.massmed.org/News-and-Publications/Vital-Signs/Back-Issues/Disclosure,-Apology-and-Offer–A-New-Approach-to-Medical-Liability/#.WyaJgS2X-u5

[Accessed May, 30 2018]

[23] Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine. Facts Improving Diagnostic Accuracy in Medicine. Available from: https://www.improvediagnosis.org/page/Facts [Accessed May 30, 2018]

[24] Berner, E.S. and Graber, M.L., 2008. Overconfidence as a cause of diagnostic error in medicine. The American journal of medicine, 121(5), pp.S2-S23.

[25] Burton, E. and Collins, K., 2014. Autopsy rate and physician attitudes toward autopsy. Medscape Pathol.

[26] Turnbull, A., Osborn, M. and Nicholas, N., 2015. Hospital autopsy: Endangered or extinct?. Journal of clinical pathology, 68(8), pp.601-604.

Note from the author:

I was personally affected by misdiagnoses in the past and suffered permanent disability because of it. I am also an activist for people with chronic and rare diseases, and therefore know some of the described patients quite well. However, having personal experiences and being closer to affected people does not cloud my judgment; it strengthens my motivation to find out more about those issues and gives me helpful insight.

Getty photo by Rawpixel