“On a scale of 1 to 10, how bad is your pain?”

The dreaded question among those of us with chronic pain. Many of us don’t know how to quantify it. Some aren’t sure we’re giving the “right” answer. And we end up picking a random number just because we are expected to (not 10, because they’ll never believe us!).

Pain scales, while often nerve-wracking, do have a place. Quantifying pain isn’t just arithmetic. It’s a vital step in getting the proper treatment. It helps health care providers understand the severity of pain, measure the effectiveness of treatments, and adjust those treatments if necessary. Think of it as the Yelp review of your bodily discomfort — rating your pain can guide you and your health care provider toward the best treatment option. However, not all pain scales are created equal.

What Is a Pain Scale?

A pain scale is a tool health care providers use to assess and quantify your pain level. The purpose of using a pain scale is to help guide treatment decisions and monitor the effectiveness of interventions. Various pain scales exist, often designed to be appropriate for different age groups, conditions, and populations.

How Do Pain Scales Work?

At the core of it, pain scales are designed to give health care providers a snapshot — albeit sometimes a blurry one — of your current pain experience. You’re asked to gauge your pain using a predetermined system: numerical, facial expressions, or descriptive words. Then, that “score” becomes a data point, one among many that your health care team uses to make decisions about your treatment.

Types of Pain Scales

The necessity for accurate pain assessment has led to the development of various types of pain scales. These tools, ranging from numerical to observational, offer health care providers essential insights into patient discomfort, aiding in targeted treatment and effective pain management. Some of the most commonly used pain scales include:

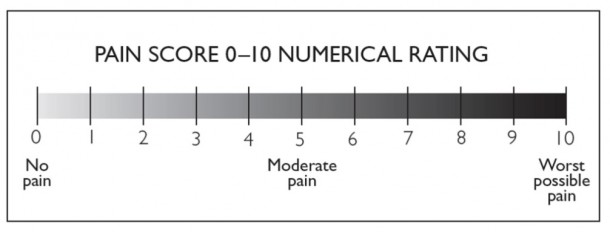

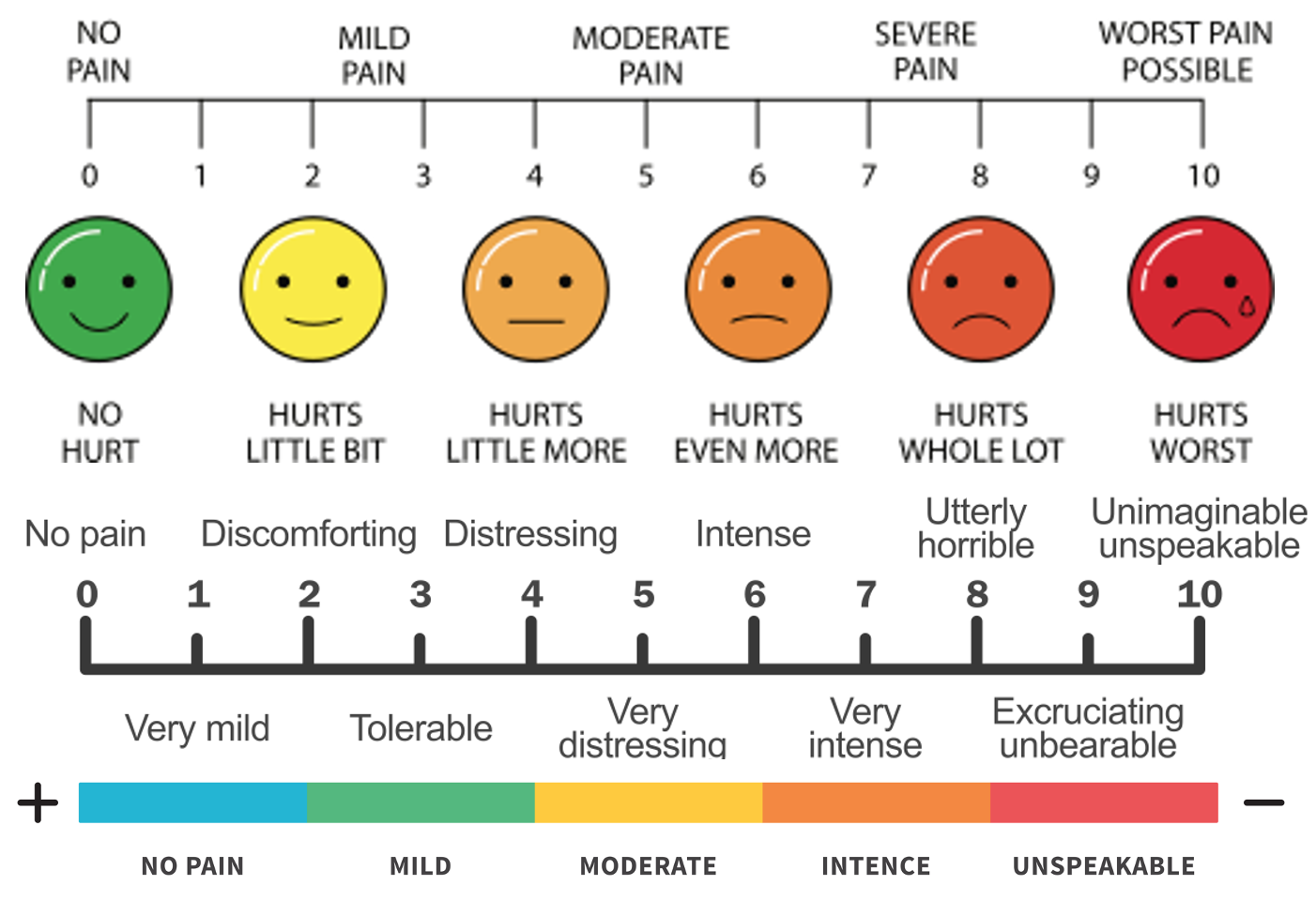

Numerical Rating Scale (NRS)

This is one of the most straightforward and commonly used pain assessment tools. Patients are asked to rate their pain on a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 represents “no pain” and 10 means “the worst pain imaginable.” The NRS can be administered verbally, in writing, or visually with the numbers displayed.

Visual Analog Scale (VAS)

This scale typically consists of a 10-cm-long horizontal or vertical line. One end of the line is labeled “no pain,” and the opposite is labeled “worst pain imaginable.” Patients mark a point on the line to indicate the intensity of their current pain. The distance from the “no pain” end to the mark is then measured to give a numerical value, usually in millimeters, to represent the patient’s pain level.

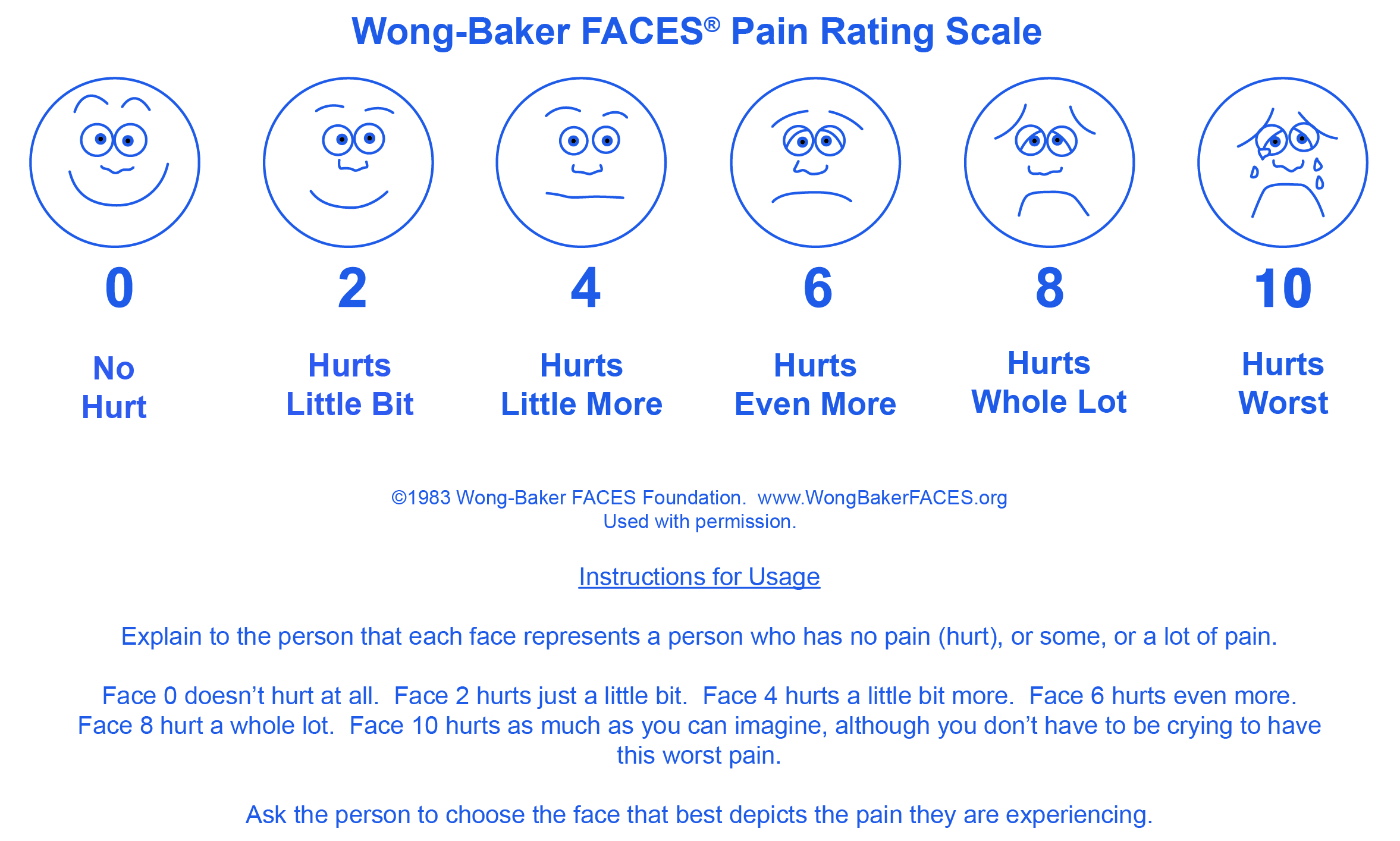

Faces Pain Scale

This scale is commonly used to help children express their level of pain. It consists of a series of faces that range from a smiling face (indicating no pain) to a grimacing face (indicating severe pain). Children are asked to point to the face that most closely represents how they are feeling. Each face is usually associated with a numerical value to quantify the pain for documentation and treatment planning.

Verbal Rating Scale (VRS)

On this scale, people describe their pain using standardized words or phrases like “mild,” “moderate,” “severe,” or “excruciating.” The terms can be ranked in order of severity and are sometimes assigned numerical values for easier documentation and analysis.

McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ)

This is a more complex and comprehensive tool for assessing pain. It includes a series of descriptors across multiple dimensions of pain, like sensory (e.g., throbbing, stabbing), affective (e.g., tiring, nauseating), and evaluative (e.g., unbearable, intense). Patients choose descriptors that best fit their pain experience, often ranking them as well. The MPQ usually includes a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for pain intensity.

Comfort Scale

The Comfort Scale is often used to assess pain and distress in critically ill or non-communicative patients, including infants and children. It considers multiple parameters such as alertness, calmness, respiratory response, and physical movement. Each parameter is scored, and the total is used to estimate the patient’s level of discomfort or pain. In some versions, physiological measures like heart rate may also be included.

Brief Pain Inventory (BPI)

This is a self-report questionnaire designed to assess the severity of pain and the impact of pain on daily functions. The BPI typically includes questions that ask patients to rate their pain on a scale from 0 to 10, similar to the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS). Additionally, the BPI asks about the locations of pain, pain relief, pain quality, and how pain affects mood, walking ability, everyday work, relationships, sleep, and enjoyment of life.

FLACC Scale (Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability)

This observational pain assessment tool is commonly used for infants, young children, and those who cannot verbally communicate their pain. Health care providers or caregivers assess and score each of five categories: face, legs, activity, cry, and consolability. Each category is rated from 0 to 2, and the scores are then summed to give an overall pain rating ranging from 0 to 10.

The FLACC Scale is an important tool for assessing pain in non-verbal populations and offers the advantage of a standardized, quick, and multi-dimensional assessment. However, it has limitations in terms of observer bias and the range of patients for whom it is most suitable. It is often used with other assessment methods to understand an individual’s pain better.

Doloplus-2 Scale

This observational pain assessment tool is designed explicitly for evaluating pain in those who cannot communicate effectively, such as those with cognitive impairments or severe dementia. The scale consists of 10 items divided into three sub-scales: somatic pain, psychomotor reactions, and psychosocial reactions. Health care providers observe and score each item based on specific behaviors or signs. The scores are then summed to give an overall pain rating.

CRIES Pain Scale

This neonatal postoperative pain measurement score assesses pain in newborns and infants (typically up to 6 months old). The acronym CRIES stands for the variables considered: crying, requiring oxygen (for saturation), increased vital signs, expression, and sleeplessness. Each variable is scored on a scale, and the total score can range from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating more significant pain or discomfort.

Mankoski Pain Scale

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/pain-5c1935b3c9e77c0001220a2f.jpg)

This descriptive pain scale ranges from 0 to 10, similar to the Numerical Rating Scale. However, it goes a step further by providing detailed descriptions for each number on the scale, often combining a verbal descriptor with information about how the pain affects function or activity. For example, it might describe a level 4 as “Pain that can be ignored if you are involved in your work, but still distracting,” and so on.

Defense and Veterans Pain Rating Scale (DVPRS)

This is designed specifically for military service members and veterans. It combines a standard numerical rating scale (0-10) with color coding and descriptive terms to indicate the severity of pain. Additionally, it often includes supplementary questions regarding the impact of pain on daily activities, sleep, mood, and stress, offering a more comprehensive view of how pain affects an individual’s life.

Behavioral Pain Scale (BPS)

This scale is commonly used to assess pain in non-communicative adult patients, often sedated or intubated in intensive care units. The scale focuses on three primary behavioral indicators: facial expression, upper limb movement, and ventilator compliance or vocalization. Each parameter is observed and scored on a scale from 1 to 4 or 5. The scores are then summed to produce an overall pain assessment.

Adult Non-Verbal Pain Scale (NVPS)

This is designed to assess pain in people who cannot verbally communicate their pain, such as those who are intubated, sedated, or cognitively impaired. The scale evaluates multiple parameters like facial expression, body movement, muscle tension, vocalization, and response to consoling. Each parameter is scored, and the scores are summed up to provide an overall pain rating.

Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT)

This is used to assess pain in critically ill adults who cannot self-report pain due to sedation, mechanical ventilation, or other reasons. The CPOT evaluates four dimensions: facial expressions, body movements, muscle tension, and compliance with the ventilator (or vocalization in non-intubated patients). Each dimension is scored on a scale, usually ranging from 0 to 2 or 0 to 3, and the scores are summed to provide an overall pain rating.

Traffic Light Pain Scale

View this post on Instagram

This is a simple and visual tool designed to categorize pain levels into three main categories: green (no or mild pain), yellow (moderate pain), and red (severe pain). It is often used for quick assessments and is designed to be easily understood by people of various age groups, including children. The scale may be supplemented with numerical ratings or descriptive terms for each category.

Abbey Pain Scale

This is specifically designed to assess pain in people with dementia who cannot communicate it effectively. The observational scale evaluates six categories: vocalization, facial expression, body language, behavioral change, physiological change, and physical changes. Each category has various items rated on a scale, typically ranging from 0 to 3, where higher numbers indicate more severe indicators of pain. The total score is summed and categorized into different levels of pain severity.

UCLA Loneliness Scale

This is a questionnaire used to measure an individual’s subjective feelings of loneliness as well as feelings of social isolation. Developed at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), the scale has gone through various versions, with one of the most common versions containing 20 items. Participants respond to various statements about their feelings and experiences, usually on a scale from 1 (“never”) to 4 (“often”). The sum of the scores provides an overall measure of the individual’s loneliness and social isolation level.

This is not an exhaustive list but covers many of the most commonly used pain assessment tools in various clinical and research settings. Each scale has its specific target population, advantages, and limitations.

Limitations of Pain Scales

While pain scales are valuable tools for assessing and monitoring pain, they have several limitations, especially for people with chronic pain.

- Fluctuating subjectivity: Pain is as subjective as your Netflix recommendations. What’s a mild inconvenience for one person can be debilitating for another. For people with chronic pain, the personal nature of pain scales becomes more complex. What you rate as a “6” today could be an “8” tomorrow, even if the pain feels similar due to shifts in tolerance or emotional state.

- Reliability: No pain scale is foolproof, especially for chronic pain patients with complex, multi-layered experiences. Yet, these scales offer a starting point for conversation and treatment. If a particular scale doesn’t resonate with you, speak up. Part of managing chronic pain is advocating for a care approach that aligns with your experience. You’re not just a number or a face on a chart; you’re a person dealing with an ongoing, multi-faceted condition.

- Lack of standardization: Much like how your grandma and your teenage niece use emojis differently, different health care settings often use pain scales inconsistently. While one doctor might take your “7” seriously, another may consider it “manageable” based on their subjective experience with other patients. There’s a need for a more standardized approach, especially for chronic pain management, where understanding and tracking pain over time is crucial.

- Cultural differences: Different cultures may have different ways of expressing or perceiving pain, impacting how an individual rates their pain on a scale.

- Communication barriers: Those with chronic pain may have particular difficulty articulating their pain’s persistent and complex nature. Some may have trouble understanding the pain scale or be unable to communicate their pain effectively due to cognitive impairments, language barriers, or other factors.

- Different pain types: Not all pain is the same. Acute, chronic, burning, aching, etc., might feel different, but pain scales often don’t differentiate between these types.

- Overemphasis on intensity: Chronic pain isn’t just intense — it’s persistent. Many scales focus on pain intensity but might not capture other dimensions of pain, such as its duration, location, or quality.

- Cognitive and emotional factors: Emotional and psychological states can influence how a person perceives and reports pain. Anxiety, depression, and other emotional factors might intensify the perception of pain, which may not be captured in a simple numeric scale.

- Potential for misinterpretation: In chronic pain, symbols or numbers can be misunderstood to represent emotional states rather than pain levels.

- Reproducibility: Your rating might change based on your current emotional state, fatigue, or even the setting in which you’re asked. Thus, repeated measures might only sometimes be consistent.

- Biases: The ongoing nature of chronic pain may lead to either underreporting (to avoid seeming weak) or overreporting (to seek stronger medications).

- Limitations in specific populations: Traditional scales often don’t accommodate those who can’t easily communicate yet may be experiencing chronic pain (e.g., non-verbal patients).

- Overreliance: Solely relying on pain scales can miss other clinical indicators in chronic pain patients, who may report low numbers but be in high distress, and vice versa.

- Influence of previous experiences: Previous experiences with pain can influence your current pain rating. Someone who has experienced severe pain in the past may rate a recent painful experience lower in comparison.

Despite these limitations, pain scales are still crucial to pain management. They provide a starting point for dialogue about pain and can help guide treatment decisions. However, health care providers should consider these limitations and use a holistic approach when assessing and treating pain, combining scales with clinical judgment and other assessment tools.

Having a say in your health care journey is empowering, pointing at a number or a face and saying, “That’s me; that’s how I feel.” For health care providers, it’s a crucial piece of data in the complicated puzzle of chronic pain management. Understanding pain scales is more than just academic; it’s a tool for a better quality of life.

Getty image by ina9