In 1971, two individuals from McGill University developed the McGill Pain Questionnaire. It includes questions about the type and quality of pain that an individual may be experiencing. If you have ever gone to seek medical care for any type of pain, whether acute (sudden and short-lived) or chronic (lasting longer than six months) you have likely been presented with the McGill Pain Questionnaire.

McGill is also known for its Pain Scale, which displays various painful conditions on a pillar that ranges from least painful conditions to most painful conditions. The scale begins at zero (no pain) and ends at the very top at 50 (most painful). It provides a relative idea of pain severity, ranging from a fracture to childbirth, to cancer pain and everything in between.

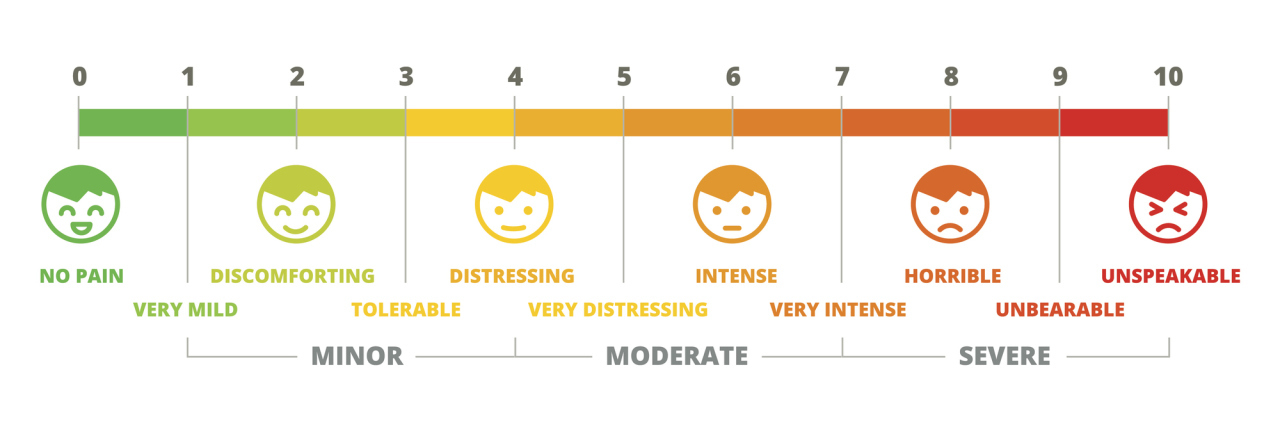

Another more familiar pain assessment used by physicians is the Wong-Baker Faces Pain Rating Scale. This pain scale is a series of faces that represent what different levels of pain “should” look like. Beneath each face is a number, ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (the worst pain imaginable). Patients are asked to look at the faces and circle the number underneath the face that best represents how their pain makes them feel.

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is known as one of the most painful conditions that exists. On the McGill Pain Index, CRPS is rated at nearly a 48 out of 50. As someone who has been living with CRPS for almost nine years, I have been to my share of pain management physicians, neurologists, and other specialists in search of pain relief. Nearly every doctor’s office I’ve been to has included either the McGill Pain Questionnaire, or more commonly, the Wong-Baker Faces Pain Scale.

When I was first diagnosed with CRPS, and first introduced to these pain assessments, I had patience with them. I would take my time, look through each option diligently and pick the one that most accurately described my pain and how my pain made me feel. Now, with CRPS being rated a 48 out of 50 on the McGill Pain Scale, nearly every time I would rate my pain a 9 out of 10 on the Wong-Baker Faces Pain Scale, because that is what it really was to me. But the longer I lived in pain, the more pain management specialists I saw, and the more pain assessments that I filled out, the more I realized I could not be honest about my pain level.

I began to “pick” a number to make it more believable for the provider. I sped through the paper work, not taking time to look at the options, giving it no thought, picking the same answers over and over like a robot that had been programed to fill out the forms a certain way and pick the same answer every time. I would even leave some questions blank at times due to frustration that no one would even bother to look at my questionnaire or take it seriously. There were times I began to notice that I was treated differently when I rated my pain so high. I would get funny looks from people, and it would even create an awkward environment. Comments were often made to me, such as, “There is no way your can sit here so quietly if your pain level is that high,” or my favorite, “If your pain was really that bad, you would be in the emergency room screaming and crying.” Rating my pain for what it really was didn’t affect my treatment plan or add any sense of urgency. If anything, it added a component of non-belief and created more problems. So I learned to compromise.

After a few years of being honest, I changed how I rated my pain level. I began to settle with a number that was high, but not too high, but not too low so as to get the point across without seeming like a “drama queen.” The number I settled on, was a happy and content eight. It also depended on the day I was having. On a “good day” I would rate my pain at a six or a seven, even if it was really an eight. On a bad day, I would rate it an eight, even if it was really a nine or a 10.

From that point on, the funny looks and the hurtful comments were no more, and my appointments became much simpler. Yes, it’s a lie, and it doesn’t truly depict how I’m feeling or how my pain affects me. Pain scales are a wonderful tool to have, but they are not the complete picture. Sometimes life is about compromising and choosing your battles.

The one thing I’ve learned from living with CRPS is that pain is subjective. Pain is what the patient says it is. No one else can experience your pain, and you are the only one who truly understands how your pain affects you. No pain scale can reveal that.

We want to hear your story. Become a Mighty contributor here.

Thinkstock Image By: GrafVishenka