When it was new, rich and earthy coffee grounds were packed neatly to its rim, their strong, full aroma hidden away under a tightly sealed lid. Until every morning when a Coffee Connoisseur or a Java Junky — both in desperate need of a caffeine jolt – hastily scooped the fragrant beads of brew into water hot enough to awaken their promise of perk.

But with its label cursorily peeled from its body, leaving behind tiny, white flecks of manufactured stamp, it was nothing more than an old, empty tin can. Until a creative coffeephile, no doubt scraping the bottom of the barrel to capture every last morsel of the hot stuff, decided to turn a used-up coffee caddy into a brand new keeper of imagination and motivation.

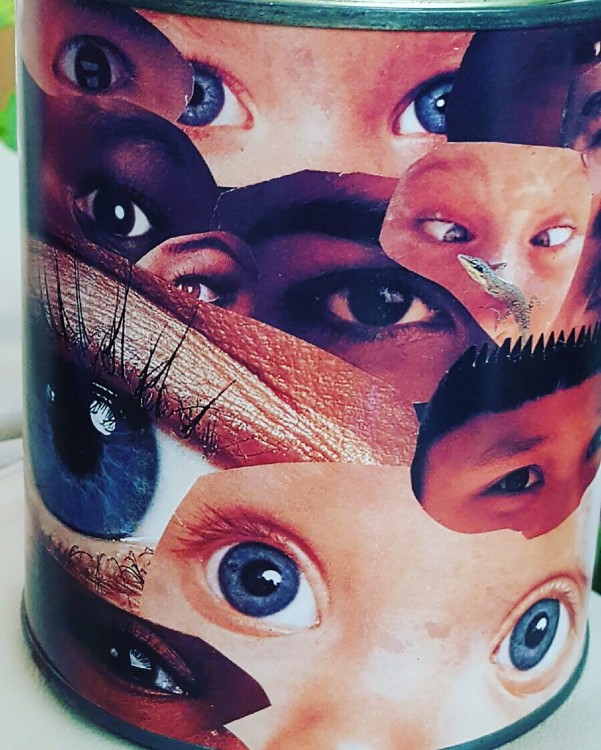

Where there was once a picture of a sleepy-eyed woman, focusing her senses on the heavy, scorched liquid she held in her cup, photographs and papier mache added portraits of eyes wide open, gazes fixed. There were optimistic eyes, sensitive eyes, heavy-lidded eyes, searching-for-hope eyes, laughing-through-hurt eyes, wrinkled and wise eyes. Every pair had seen different things, but each

was looking for more.

This metal container, once guarding contents of the artist’s most gripping vice, had been transformed into art – a giant window into hundreds of souls – and cleverly crowned the “Eye Can Can.” Its new label also held promise to spur energy and drive, but the kind that only comes from within.

The capsule, storing endless supplies of tenacity and willpower, was created by a man unlike anyone I’d seen. His raven hair, slicked back into a pony tail and revealing the sharp edge of his jaw – dulled slightly by the dark shadow across his face – was the same color as the leather jacket he wore and the wheelchair he rode. Intimidation kept me from speaking to him until he broke through the art fair crowd – and my walls.

“Hi, sweetheart,” he called out as his deep-set hazel eyes danced behind dark-rimmed glasses. I was instantly enamored by his unexpected kindness and quiet confidence, but also by the way he moved through life. Fast but deep conversation uncovered that, years before this moment, a motorcycle

accident rendered him paralyzed and unable to move much above his neck. He controlled the joystick of his chair, and each careful stroke of his paintbrushes, with his mouth. An innovative artist, indeed.

Attentively, I observed him and the steady intent with which he guided a blue-tipped brush across blank canvas. Turning in his teeth, the thin brush followed clear direction of his head’s small, subtle movements. Slowly emerging from his mind’s eye, delicate flower petals fell to the fabric. Unparalleled, his talent astounded me.

My attention stayed locked as he welcomed me into his creative mind, but from the corner of my eye,

I watched as others watched him, and us together. This picture of two people, one adult and one child, should have been nothing odd or uncommon. But adding wheelchairs made others view us differently.

I quickly realized that through untrained eyes, the rest of the world saw a man trapped in his own body, whose abilities didn’t extend far beyond the occasional blink of an eye or twitch of the nose. But I saw much more.

What captivated me most was his conviction, unshaken. People silently assessed and evaluated his capabilities and potential, but he paid no mind to the results. He knew that although permanent injuries from an unexpected accident changed some faculties of his physicality, his skill, his mastery, and his artistic prowess remained intact. He wasn’t going to let a doctor’s diagnosis or a stranger’s judgment stop him from being a leather-wearing-motorcycle-loving-rock-n-roll-listening-oil-painting

artist. He wasn’t going to let his disability stop him from being himself. Our eyes locked like magnets, and he told me that I shouldn’t either.

That single moment changed my life. Up until that point, I spent a lot of time around adults (read: therapists and doctors with “specialist” embossed on their name tags) who thought they knew more about me and my abilities than I did. Every time I laid on an examination table, feeling the stiff, white paper cringe and crinkle under the weight of my nervous body, every time I tried to stay “stiff like a log” on an X-Ray table, waiting for the light to zero in on all the places my body needed fixing, every time I demonstrated the ways my legs or arms moved while a physical therapist scribbled illegible notes, wondering what they said about me and the kind of person I would turn out to be. Every time, I felt broken. Less than. Wrong. I felt like I was full of mistakes. Up until then, no one told me I was strong, capable and exactly who I was supposed to be.

“Keep all your dreams inside this can,” he requested. “Whenever you feel like life is too difficult or impossible, look at it and remember that you can do anything. Anything is possible.”

I was probably too shy to speak, but these words of encouragement from a super rad, way cool, kinda scary adult – who just happened to sit in a chair like me – sent shock waves through my system. Holding my own “Eye Can Can” felt like holding the key to my life. For the first time, I believed I could do anything. Go anywhere. Be anyone. For the first time, I had the courage to chase my dreams and confidence to reach them.

After that day, an empty tin can decorated with a collage of corneas sat high atop my bedroom shelf, collecting pens and stickers and folded up notes and old movie stubs and school pictures and probably a little dust. But every time I filled it up with little moments and memories from my life, I remembered the man who gave it to me. I replayed his words on a loop in my head and I took them with me.

I took them with me when I made the terrifying decision to move to Florida for college, despite a few pesky adults (read: advisors and school psychologists with fancy, embossed name tags) wondering “if it was really a good idea” and “if I had thought it through.” I took them with me when I applied for internships and jobs, all the while wondering if employers would give a girl in a wheelchair a real shot, and hoping that they would. I took them with me when I signed my first lease and moved into my first home on my own, the entire time fighting fears and doubts. And I take them with me today, when

a project at work feels too daunting and I don’t know where to begin. I take them with me when I’m exhausted and really not sure I can do this adult thing for one more day.

Adversity is an unfortunate side effect of life, and it does not discriminate or distinguish. But if we’re willing, we can accept challenges as gifts that demonstrate our strengths and develop our character. Too often, people with disabilities are told to stop at the edge of a challenge. They can take the easy road because the other way might be too difficult and they might struggle.

So what? What’s wrong with living and learning?

People with disabilities aren’t broken, less than, wrong or full of mistakes – they’re strong, capable and exactly who they’re supposed to be.

Now I’m a super rad, way cool, kinda scary adult who just happens to sit in a chair. And I know “Eye Can” do anything. Anything is possible.