“Why do you think he’s in a wheelchair?”

My 4-year-old daughter pointed to the outline of the man pushing the large wheels of his chair on the page in front of us.

“I’m not sure,” I answered honestly. “Maybe he hurt his legs, or maybe he got sick and his legs aren’t strong enough to walk.”

Whatever the reason why the character in the book we sat reading on a beanbag in the library was in a wheelchair was much less important than what was happening at that moment with my daughter – learning about someone who is different than her.

The beauty of reading is that it can transport us to faraway places, time periods in the past or the future, even worlds only alive in our imaginations. But reading does something else: it allows us to learn about each other. It enables us to imagine how we may feel in situations we have never been in or to appreciate someone’s life that we have never met – developing empathy for those we encounter throughout our lives.

Through the characters who grow within a well-told story, books foster new ideas, new cultures, new ways of living. Instead of pity, we can come to better understand. Instead of apathy, we can learn to connect and bridge. Instead of intolerance, we can learn to celebrate how uniquely we were all created.

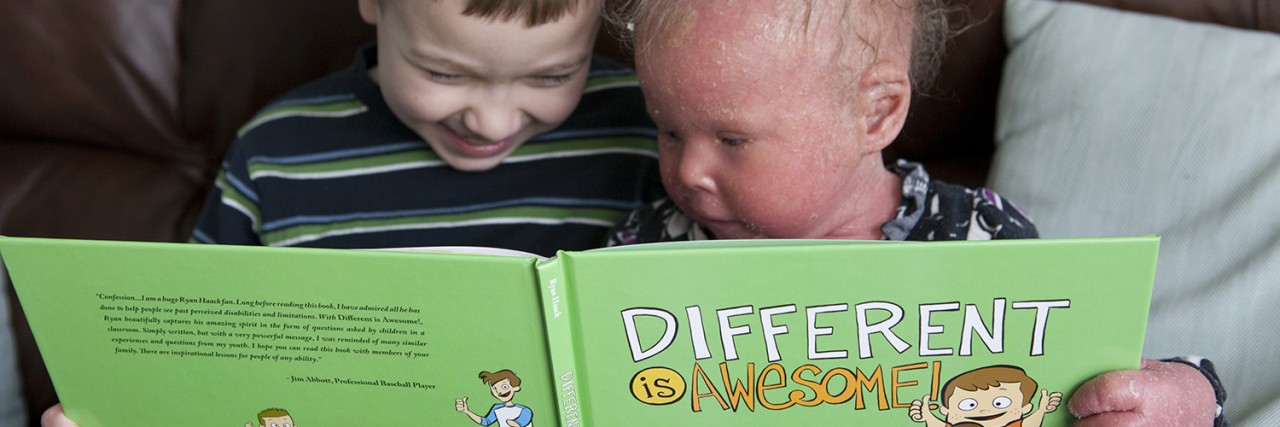

When my daughter was born four years ago, we were given the shocking news of a rare diagnosis: a severe genetic skin disorder. Today, she is the size of a child half her age, with skin that appears like a terrible sunburn – and she is often the object of open-mouth stares, pointing and questions.

Because of this, we began to discover firsthand how important these (often difficult and all too rare) conversations are with our children, how essential it is to explore our differences – both inside and out. Kids learn by asking and seeing and experiencing, and we need to not relegate the subject of difference to a taboo topic.

And even though my daughter deals with her own differences, I’ve found that doesn’t mean she is immune from needing to learn about others’ differences. She may have more empathy or understanding on a basic level when she sees a child who is different from her, whether it’s size or skin color or disability, but she is still curious about others, the same way that others are curious about her.

If we want our children to know how to be respectful and choose kind words, to be kind-hearted and empathetic individuals, it starts with us as parents. And to give our young kids these experiences, the pages of a book are a wonderful place to open these conversations, so that they can begin learning to appreciate the differences of other people before encountering them.

Let us not be more concerned about teaching our children about how to excel at sports or master sight words than about how to treat each other, especially those people among us who may be very different than we are. Different doesn’t have to mean strange or uncomfortable if we look for points of connection and strive to learn more about each other in respectful and appreciative ways. After all, we are much more the same than we are different.