Black Disabled Man Dies From COVID-19 After Texas Hospital Refused to Treat Him

A Black disabled man died from COVID-19 in Austin, Texas, after doctors declined to provide hydration, nutrition and treatment based on a “quality of life” decision. Disability advocates highlighted that the discriminatory attitudes behind these “quality of life” decisions are rampant — and dangerous.

Michael Hickson, who was married and had five children, was hospitalized for COVID-19 on June 2 at St. David’s South Austin Medical Center in Texas. According to the Texan, Hickson had a brain injury and was a quadriplegic following a 2017 heart attack. He was living at the skilled nursing facility Brush Country when he was admitted to the hospital for COVID-19. By June 3 he was in the intensive care unit.

A few days later, Hickson was unexpectedly removed out of ICU. Hickson’s wife, Melissa, was told he was stable and breathing on his own but had been transferred to hospice care. While initially Melissa was told Hickson would still receive fluids and nutrition through his percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube, the hospital withheld all care.

The doctor for Michael Hickson, who was quadriplegic, said "So as of right now, his quality of life — he doesn’t have much of one." "Quality" was already skewed against disabled people but covid-19 has amplified this.https://t.co/EaxBqfFmga

— Eric Michael Garcia (@EricMGarcia) June 30, 2020

Texas Right to Life published a conversation on YouTube allegedly between Melissa Hickson and a hospital physician, telling Hickson’s wife the hospital wasn’t considering more aggressive COVID-19 treatment — or any treatment. The decision, the doctor can be heard saying, hinges on Hickson’s quality of life.

“The issue is, will this help him improve his quality of life. Will this help them to improve anything? Will it ultimately change the outcome?” the doctor said. “Because as of right now, his quality of life, he doesn’t have much of one.”

The doctor confirmed to Melissa that Hickson’s brain injury and disability were major factors in their decision. Melissa asked the doctor, “Being able to live isn’t improving quality of life?”

Typically, triage policies that assist doctors in making difficult decisions about how to prioritize care with limited resources are only enacted when a hospital is at capacity. Not Yet Dead, a grassroots disability organization against assisted suicide, pointed out that it’s unclear why Hickson’s doctors used triage policies in this case. There’s no indication St. David’s South Austin Medical Center was at capacity.

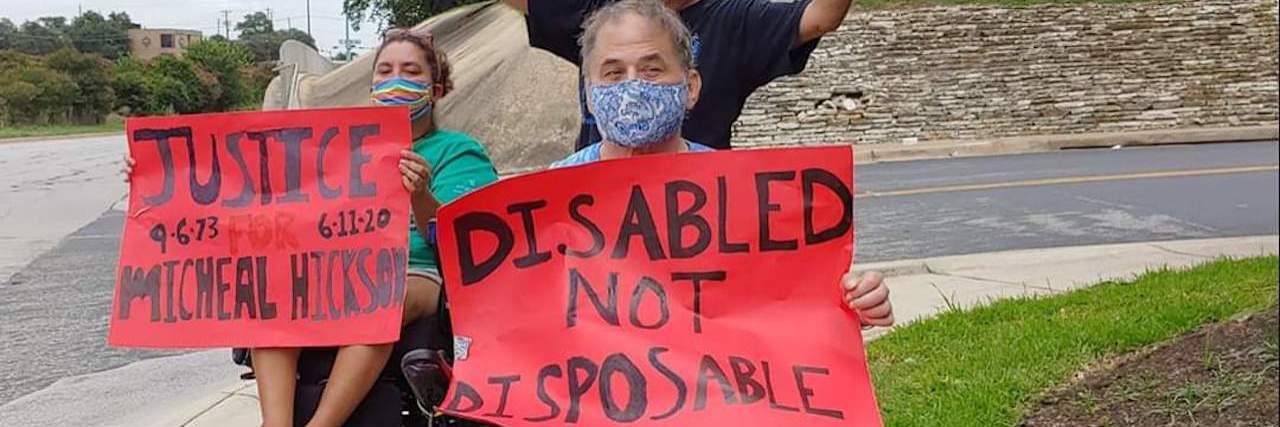

ADAPT of TX is outside St. David's Hospital in Austin demanding justice for #MichaelHickson, a disabled black man, who was denied treatment and food and died on June 11, 2020 #DisabledNotDisposable #LivesWorthyOfLife #BlackDisabledLivesMatter pic.twitter.com/6i87alQM1j

— ADAPT National (@RealNatlADAPT) June 28, 2020

But triage policies are already inherently ableist.

On Wednesday, Arizona enacted its Crisis Standards of Care, which involves a scoring system to determine which patients should be prioritized for treatment. Based on Arizona’s standards, people with pre-existing health conditions, disabilities and seniors are deprioritized based on the length and quality of life determination, as estimated by medical doctors. These guidelines violate civil rights protections for people with disabilities.

“The Crisis Standards of Care (CSCs) activated in Arizona should be revised immediately and brought into compliance with civil rights protections that bar discrimination on the basis of age or disability,” Matt Valliere, executive director of Patients Rights Action Fund, said in a statement. “Faulty prognoses only increase the chances that people with disabilities, the elderly, and other vulnerable groups will not receive equal care if they become sick because their perceived quality and length of life may be less than others.”

The Mighty’s disability editor, Karin Willison, explained early on in the coronavirus pandemic that the ableism rampant in the U.S. health care system was perhaps the biggest threat to the lives of people with disabilities. Willison wrote:

These rationing policies are a symptom of the deep ableism ingrained in the medical profession. People with disabilities are often seen as less worthy of care, less valuable as human beings. … If the system itself does not protect people with disabilities and chronic illnesses, some of us will pay the ultimate price at the hands of those who do not see our value.

TW: death, #COVID19

They let a black disabled man, #MichaelHickson starve to death after they denied him care for #COVID19 in Texas.

The doctor said it wouldn’t be worth saving him because of his disability.

I am disgusted.

This is the moment masks-off people wanted. https://t.co/2eRsLkuHJ4

— Crutches&Spice ♿️ : Rude For A Disabled Person (@Imani_Barbarin) June 28, 2020

Hickson was also Black. Black people face added discrimination in the health care system as well as a higher risk for getting COVID-19.

Compared to White women, Black women are three times more likely to die during pregnancy. Black people also have a higher risk of dying from cancer and other illnesses. Meanwhile, access to care remains out of reach for many Black families. According to a Century Foundation report, Black people are more likely to be uninsured than White people. In addition, for those who do have health insurance, the premiums comprise about 20% of their household income.

Black people are also more likely to have underlying conditions like diabetes or high blood pressure that increase the risk for COVID-19. This is in large part due to systemic inequities in the health care system that bar access to affordable care. BIPOC people are also more likely to work in low-wage jobs now considered “essential,” increasing their risk for COVID-19 exposure. Black men are four times more likely to die from COVID-19 than White men.

According to the Texan, Melissa Hickson was facing an ongoing guardianship issue over who could make decisions about her husband’s care. While Melissa was granted temporary guardianship in probate court initially, Hickson’s sister also filed to serve as his guardian. Eventually, a judge assigned the nonprofit Family Eldercare as Hickson’s guardian as they sorted out the issue.

Family Eldercare made the decision to follow the doctor’s advice against Melissa’s wishes to withhold care from Hickson. Hickson was moved to hospice care where he died on June 11. When hospice care called to let Melissa know, they asked if she wanted the name of the funeral home where he was taken. His body was taken to a funeral home without Melissa’s knowledge. She plans to take legal action.

“I really want everyone involved to be held accountable,” Melissa told the Texan. “I want to shine a light on this. They took his only voice for his care when they silenced me. Family Eldercare was supposed to keep him safe and they didn’t.”

A spokesperson for Family Eldercare said decisions about Hickson’s care did not hinge on his disability, and the details currently available to the public about his case don’t tell the full story.

“As court-appointed Guardian, we consulted with Mr. Hickson’s spouse, family, and the medical community on the medical complexity of his case,” the organization said in a statement, adding:

As press reports have disclosed, Mr. Hickson’s spouse, family, and the medical community were in agreement with the decision not to intubate Mr. Hickson. As Guardian, and in consultation with Mr. Hickson’s family and medical providers, we agreed to the recommendation for hospice care so that Mr. Hickson could receive end-of-life comfort, nutrition and medications, in a caring environment.

A St. David’s South Austin Medical Center spokesperson said in a statement:

The loss of life is tragic under any circumstances. In Mr. Hickson’s situation, his court-appointed guardian (who was granted decision-making authority in place of his spouse) made the decision in collaboration with the medical team to discontinue invasive care. This is always a difficult decision for all involved. We extend our deepest sympathies to Mr. Hickson’s family and loved ones and to all who are grieving his loss.

Melissa highlighted that her husband had a wonderful life — in contrast to the discriminatory attitudes in many health care settings about disability.

“He regained his personality, had memories of past events, loved to do math calculations, and answer trivia questions,” Melissa Hickson told the Texan. “Why are disabled people considered to have a poor quality of life?”

Updated July 1 with comment from Family Eldercare.

Header image via ADAPT of Texas/ADAPT National/Twitter