In the inspiring and often saccharine stories of disabled people (often told by someone else) the person struggles with their illness. They are a hero, a martyr, deeply and spiritually strong because they have worked so hard to do the same things that other people take for granted. They are rewarded for this hard work with accolades, scholarships, friendships, and applause.

• What is Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome?

• What Are Common Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Symptoms?

The reality of disability is very different.

Stress symptoms, limitations, pain, fatigue, brain fog, and proprioception issues all fall into the category of things a doctor cannot codify, measure, or rate on an objective chart. Without their objective chart, too many physicians put aside concerns for things they can’t quantify. Self-reported pain goes unremarked. Unsteadiness or falling down is only noticed in the context of recovery from the injuries you sustain. Executive function issues (problems with higher reasoning, math, planning, organization) are often seen as a moral failing on behalf of the patient. They missed an appointment, or didn’t fill the prescription on time, or didn’t bring important documents.

The road to my diagnosis was not an easy one. All my life, I sprained things. School officials, other kids, even my own parents thought I was milking injuries or making mountains out of molehills. I didn’t bruise terribly when I hurt my joints, and on top of that, no one considered that I might have ongoing and sustained damage to my ligaments and tendons. I was clumsy — not in an adorable romance novel way which doesn’t exist in real life, but in the sense that people thought I was just incredibly reckless and if I was just more careful… It got worse as I aged, elasticity turning tendons and ligaments lax and degrading my body awareness. Once agile, fast, and thin, I became sedentary and afraid to move.

Loss of proprioception dealt me a huge blow. Imagine living in a body which lies to you about where it is relative to your other limbs, relative to the floor, the desk, the chair? Living in a world that becomes a threat is difficult. I dislocated my shoulder by slamming into a doorway because I turned too fast and all that spin turned into force. Stairs became legitimately frightening. Stairs without a railing held a sort of terror like a rollercoaster; could I make it down the stairs without falling? Would I know when the last step came in the dark?

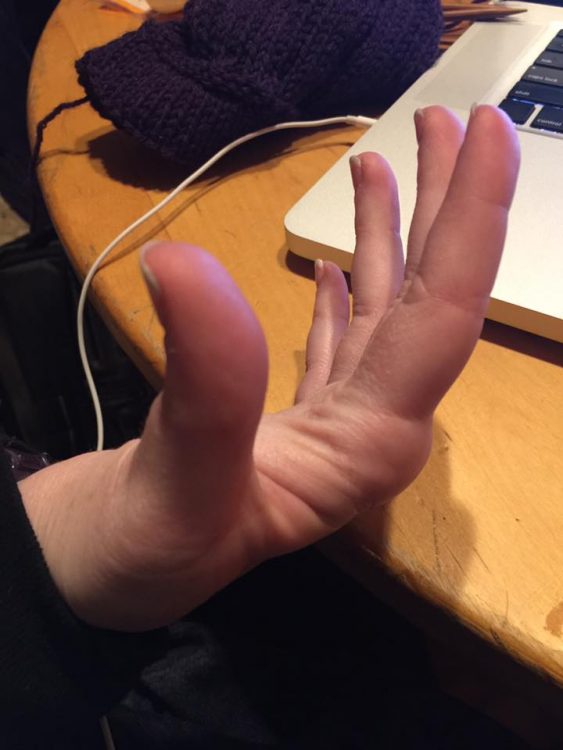

How do you explain that fear to a doctor? I swiftly earned a generalized anxiety diagnosis, which then led to benzodiazepine medications, which made me clumsier, slower, unfocused, and lethargic. It wasn’t until I was seeing a psychiatrist who noticed how far my fingers bend back that someone actually listened. I got a referral to a doctor who could see what no one else could. I started to understand what was going on.

But there wasn’t a fanfare. There was no “oh!” moment where Hugh Laurie figured out the mystery illness and everything was better, or I overcame what was holding me back and got everything I was looking for in life.

Narratives about disability never tell you this: There is no “all better” at the end of the disability tunnel. There is no swelling indie song at the end of a great triumph over something and then you live happily ever after. Scholarships and accolades and people telling you how brave you are generally only happens in the context of a viral Facebook story, and is forgotten when the next one comes along. There are no rewards for getting to a place of equilibrium with your illness. Your only reward is to keep fighting to maintain it.

Oh, there are improvements, adaptations, better meds, better crutches, better physical therapy, but fundamentally it’s a fight you’re going to keep having. That’s OK. We’re equal to it. Just keep in mind that we’re still fighting, and it doesn’t end for us. We’ll try to keep in mind that you have your own battles, too.