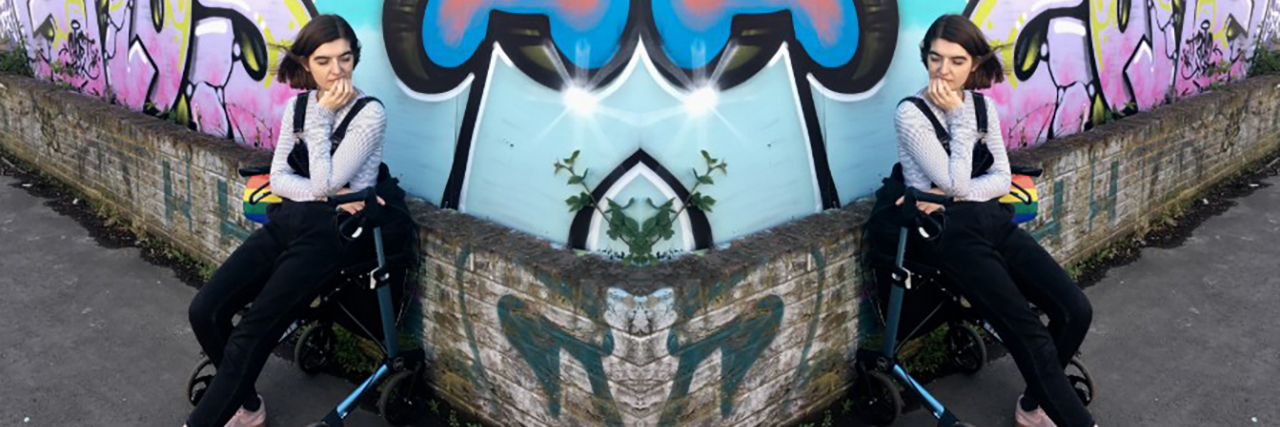

I recently started using a rollator (outdoor walker). Before getting this mobility aid I had completely stopped leaving the house by myself, only leaving the house with the assistance of my partner or my parents less than once a week. Since getting my walker, I have been going out at least once a week by myself, and between three to four times a week with the assistance of someone else.

• What is Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome?

• What Are Common Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Symptoms?

Although my partner and I are often using my walker as more of a wheelchair, this device has given me back a lot of the freedom that had been taken from me. I use the word “taken” because in theory having an illness or impairment should not restrict a person from taking part in society to the extent it does now. We live in a world with the resources, money and technology to create accessible societies, however accessibility is not viewed as a priority by many. People with the privilege of an abled body, particularly those in positions of power choose to ignore issues of accessibility, while the part they play in disabling others remains invisible to them.

I view disability through the social model, which sees disability as an “oppressive social construct.” This model sees the barriers faced by disabled people when trying to access society as a result of the inaccessibility of that society rather than the impairment of the person.

I was diagnosed with hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome in February, but have had health problems my whole life and have been significantly ill for the last four years. My mobility was hindered by fatigue, pain, spinal instability, spontaneous subluxation of various joints, dizziness and fainting. Aside from my mobility issues, I was struggling with the invisible nature of my disability in public spaces. As a person in my 20s who often appears able-bodied, I would struggle if I was expected to stand on public transport. I also found that people would push past, into or up against me in busy public places causing pain, disorientation or unnecessary stress, which would lead to an increase in heart rate and sometimes fainting due to postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS).

My judgment clouded by my own able-bodied passing privilege, I had perhaps naively thought making my illness and disability more visible would signal to other people to take greater care around me in public spaces, allowing me adequate personal space and offering me assistance on and off of public transport. However something very different happened. Although my disability was now visible, the person with that disability had become completely invisible. People were so desperate to not get stuck near or behind me that they would violate my personal space to a greater degree than before, as if I was not there at all. Avoiding eye contact, strangers rush in front of me, some tripping over the wheels of my walker. Not once have I been offered assistance getting off or on public transport, however people have felt comfortable enough to talk loudly about how sad they find my situation. Strangers have felt the need to tuck my label in without asking, tell me they will pray for me or that I am far too young to need a mobility aid.

Despite all of this I am very quickly falling in love with my rollator. Yes, I experience far more ableism than before. Yes, I am quickly discovering just how inaccessible most public spaces really are. Yes, I still tire easily and would benefit from an electric wheelchair or scooter. Yes, being ill and disabled is difficult in many ways. Yes, I am disappointed in how I have been treated in public spaces. But no, I do not need anyone’s pity for having to use a mobility aid. Mobility aid users and people who are denied access to society in many ways need positive support. They need accessibility to become a priority in how we all interact in society. In the causes we support, in how we vote, in how we act in public spaces, on public transport, when driving cars, when designing new buildings and spaces, and in how we conduct ourselves online.

Mobility aids should never be looked down on or viewed negatively. Getting my mobility aid has been extremely empowering. If you see someone in the street with a mobility aid, do not pity them, but think about how your actions may able or disable them to be in society.