Labels and I have not gotten along since the fifth grade when classmates placed me in the “not popular” and “not cool” categories. I was a chubby Hispanic girl among athletic, fair-skinned peers with sunshine blonde hair. I stuck out like a sore thumb and wasn’t at the place I am now, where embracing one’s uniqueness is practiced, accepted, and even encouraged.

Other relevant stories:

• Can You Join the Military With ADHD?

• ADHD vs. Anxiety

• How to Discipline a Child With ADHD

• What is ADHD?

Because labels can be cruel, misleading, and extremely confining, I try leaving my identified chronic conditions and lifestyle choices at the door. This allows parts of me to organically present themselves to others. It isn’t long before people can piece together the complex puzzle that is me: a neurodivergent zebra. More about that later!

I was born a “zebra,” and no, my mother didn’t deliver a newborn with hooves and stripes. Could you imagine? Most members of The Mighty community know that zebra is a term used to describe individuals with rare disease, particularly Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS). I didn’t actually know I had these invisible stripes until my pain symptoms worsened. Then came the myriad of pain-inducing diagnoses offered in 2011, 2012, 2014, and 2015. But beyond these physical conditions, I’ve always had this shadow following me, whispering that there were other, hidden abnormalities bubbling at the surface.

The signs were, at first, subtleties my loved ones and I had always chalked up as being quirks. In early 2020, however, each symptom worsened and new ones crept in. I initially thought it was job burnout because my physical health was worsening and I was feeling overwhelmed with my workload. Then those feelings manifested into my psyche, putting me in a distressing headspace. It felt as though I was heading towards a mental health breakdown of seismic proportions if I didn’t get off of the fast track I was on.

At its peak, this spiraling chapter came with hindering and paralyzing symptoms, ranging from physical surges of feeling unsafe (fight or flight response) to emotional, traumatic flashbacks. I also experienced increased migraine and cognitive function disruptions, forgetfulness, spacing out and dissociative behaviors. All this was happening despite weekly appointments with a licensed therapist I had been meeting with for diagnosed anxiety and panic disorder. Unfortunately, sessions weren’t preventing this looming shadow from growing.

The heightened symptoms continued and I was encouraged by my healthcare provider to enroll within my state’s temporary disability insurance. It was during this time the pandemic was at its worst and the two debilitating circumstances resulted in my stepping away from my professional career. I increased my therapy sessions, hopeful it would invoke some deeply seeded affliction I could banish from my daily life. If only it were that easy.

After the advice of three medical professionals and two years of emotional and mental agony, I treated myself to a very informative, yet very expensive, neuropsychological evaluation. What I envisioned as a cinematic testing experience was actually more of a long, challenging and tiring process. Part of the evaluation had me questioning whether I had any cognitive memory function at all. Other times, I felt as though how I responded could follow me for the rest of my life in the form of a societal stigmatized diagnosis. When completed, the results verified that I had been unnecessarily struggling for decades due to a number of circumstances and internal wiring.

I was diagnosed with frontal lobe and executive function deficit, multifactorial attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) — inattentive type, anxiety, depression, features of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and features of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). At first, my mind’s eye widened when I read the initial findings; it meant I’d be living the rest of my life with both physical and mental invisible illnesses. Then I took some time to digest its results and it occurred to me that the multifaceted shadow now had names.

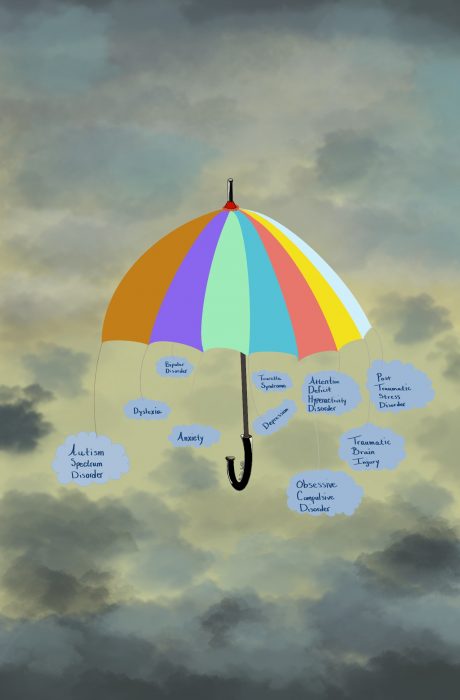

Equipped with this knowledge, I immediately began reading more about each condition. I was surprisingly comforted after learning many of the disorders fell under a catchall group that spans over a network of various conditions. There was a community for me, made up of individuals sharing similar obstacles. We are the neurodivergents. Sounds like a superhero, right? We kind of are! In its simplistic definition, neurodivergent is used to describe an individual who falls under an umbrella of conditions that includes various neurological differences. We think, process and respond to stimuli that’s considered atypical to the norm. It is not an abnormality, impairment, deficit, or handicap. Diagnostic manuals place conditions such as autism and ADHD within the neurodivergent category, along with anxiety, depression, PTSD, traumatic brain injury, bipolar disorder, dyslexia and OCD, to name a few.

Having integrated myself within the chronic pain communities over the years (shoutout to fellow zebras, spoonies and POTsies!), it seemed practical to immerse into similar groups within the neurodiverse world. This, however, was proving to be more challenging. My search discovered that individuals shy away from the neurodivergent label, so as to not be unintentionally categorized as someone living with another type of brain functioning condition. Because the label is an open-ended term, it can generate misconceptions as to a person’s capabilities and strengths, impacting a person’s ability to find success within the workplace or avoid stigmas. After reading about the neurodivergence movement, its conflicts and disagreements within its own community, the shared concerns resonated with me. I hadn’t been as openly vocal about my neuropsychological journey as I had been with my chronic pain conditions to family, friends and even strangers. Now I understand why.

As much as social and mainstream media has attempted to bring light to the varying degrees of mental illness and its general impact, I was still very much embarrassed and afraid that my conditions would be seen as flaws. I hadn’t given that much power to my physically life-altering disorders, so why did these mental conditions have such a hold on me? After asking myself that question over and over again, I experienced this pivotal moment within my psyche. There’s actually no rule that says I have to approach mental illness in the same way I did with my personal pain struggles. I can share only what I feel comfortable sharing about my mental health narrative, when I feel the time is right and with whomever I want. That incredibly freeing realization is one that I encourage you to consider, particularly if you’re overthinking whether you’re saying enough to loved ones, sharing enough with friends or are enough for everyone. You are enough.

This was such a personal shift for me because I spent years sharing intimate details about my physical chronic pain conditions through my previous policy work, encouraging others to do the same. Yes, it is powerful to unfold your experiences with others, but there are reasons for doing so. With my previous position, the reasons were to encourage positive legislative changes for the pain community. But I’m not currently meeting with lawmakers, I’m not training advocates about mental health disparities or attending committee hearings and testifying. I’m not playing an active role within the mental illness advocacy space, so I shouldn’t feel obligated to set an example for others unless I choose to become a resource for others. I can find my own rhythm, move at my own pace.

By accepting this truth, it took away the pressure of feeling the need to share my skill sets and keep up with the fast-paced social culture. Career goals should not be built upon the idea that you need to work long hours, never say no and always put others before yourself. I’ve gifted myself space and time to not only try and let go of impressing others through my professional successes, but to find out what my mental health needs are so I can thrive moving forward. This career hiatus has been messy and frightening, but it was necessary.

I’ve recently adjusted my psychotherapy plan, trying a new therapeutic technique called eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR). I’ve also taken up natural science illustration as a wholesome hobby I may wish to pursue more seriously down the road. I’ve chosen to associate with the term neurodivergent personally because the majority of my conditions fall under the umbrella and it’s easier to use one word than to list my six identifiable disorders. I merged my two labels, neurodivergent and zebra, into one term through a social media account I created: Tiny Zebra Notes. It’s my way of processing the reality that I live with both chronic mental and physical disorders through humor and encouragement. My hope is that the account reflects that we are not alone. We are strong, and unique neurodivergent zebras.

Getty image by Drazen