I am a strong advocate for portraying the positives of any situation. There is no use in focusing on the negatives that cannot be changed. Despite this, I realize that maintaining an incessant happy happy joy joy demeanor is unrealistic.

I had my first feeding tube placed at 16 years of age due to a condition called gastroparesis. Prior to that though, the prospect of a tube was threatened by my doctors on numerous occasions. Yet, they failed to offer explanations, good or bad, about the device that supposedly saves lives. I was left with, “OK, you are starving. Here is a feeding tube. Now you won’t die.” I had to form my own conclusions and a feeding tube seemed like the worst possible outcome. The prospect was petrifying.

All of my energy went into avoiding it. Stepping on the scale was a tear-inducing ordeal. As the number on the scale decreased, I knew I could not continue in a state of malnutrition. And then I was tubed. Initially, resorting to tube feeding seemed as if I had given up. It was like I had lost the fight, succumbing to hell that meant living with a feeding tube.

Shortly after my GJ feeding tube surgery, I realized how incorrect I was. My life had changed, but it was not for the worse as the doctors previously implied. It was for the better. My quality of life had drastically improved. I was less nauseated, had energy and my fainting and blackouts lessened. I became thrilled about life again because my feeding tube opened a world of new possibilities. I anticipated the future with excitement rather than nervous dread of the unknown.

So, I try to raise feeding tube awareness centered around the good – the positive outcomes not often spoken about. Still, an important facet of awareness is authenticity. Just as medical professionals fail to mention the positives of a feeding tube, they do not even begin to cover the challenges. It would be wrong of me to pretend that they do not exist and to claim that I did not once believe in the plethora of feeding tube misconceptions.

1. I would tolerate the feedings and my symptoms would disappear.

Food and I were obviously not working out. A feeding tube meant I did not have to rely on consuming food for survival. Problem solved, right? Such an assumption was a bit misled. In my case, the issue was not food, but my GI tract. Placing a feeding tube does not heal my faulty GI tract. It is simply a tool that makes the intake of nutrition a little easier. There is no guarantee that formula will be tolerated without symptoms.

2. Complications would not happen to me.

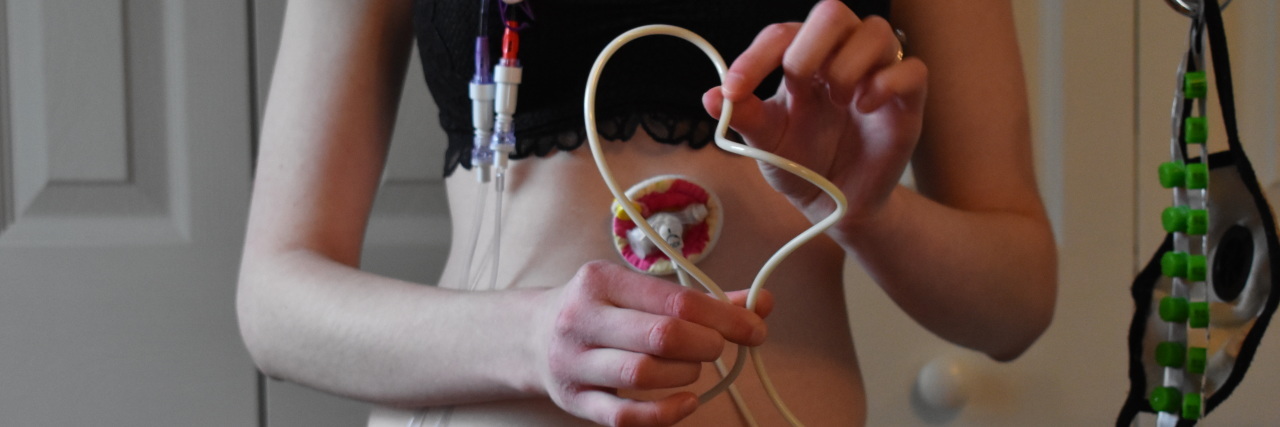

Infection, buried bumpers, tube migration, stoma burns, granulation tissue…complications are real. No tubie is immune to them. While encounters with feeding tube complications may be few and far between, it is still important to be meticulous about feeding tube care to make tube feeding as problem-free as possible!

3. I would never feel hungry.

I was under the impression that I would never want food due to how ill it makes me. Despite having a feeding tube, I do get hungry and I do crave regular food. Thankfully, I will not exhibit physical signs of hunger when receiving sufficient calories through my feeds. If circumstances require an increase in calories, like if sick with a virus, hormonal influences, etc., then my stomach will start growling and I do feel hungry. Coping with hunger is unpleasant at times.

4. The tube stoma does not hurt after the initial surgery.

My feeding tube site, the stoma, is always super sore. There are various explanations for stoma pain. After the initial surgery, the pain in my abdomen was comparable to working out and doing lots of sit-ups. Within a full month, that muscle soreness pain completely dissipated. However, it was replaced with a new pain.

The body attempts to close the new wound during the healing process, but it can never fully heal because the tube is holding the stoma open. That results in a buildup of tissue around the stoma called granulation tissue.

With the tube present in the GI tract, the body’s natural instinct kicks in. The stomach tries to digest the tube. Although the tube is held in the stoma by the internal bumper, digestion causes movement of the tube – a feeling similar to a spasm and like the tube is sucking in and out. Healing, movement from digestion and daily activity all contribute to granulation tissue. Granulation is perfectly normal, and some have it worse than others, but it hurts!

5. I cannot eat for pleasure.

A feeding tube definitely does not prevent a patient from consuming food orally, nor does it mean that they should not try (unless a doctor advises otherwise, of course)!

6. I wouldn’t mind if I were connected to a pump the majority of the day.

The amount of time I am connected to run J tube feeds has differed depending on my health. It is rarely less than 12 hours. Typically I run feeds for 16-18 hours. Tubing, a feeding pump and a backpack is my best friend for the duration I am on feeds. I usually accept that fate with a smile. Inevitably the tubing starts to tangle, air gets in the line or I am restricted from an activity… and then feeling “tethered” to tubes and lines is incredibly frustrating. No matter how many melodramatic “just pull out my tubes and let me die” moments I must endure, a feeding tube is a small price to pay for being alive.

This story originally appeared on Hospital Princess.