You never forget the moment you watch your father take his last breath. It’s something that is burned into your memory forever. It’s not morbid, or sad, or heartbreaking. It’s peaceful.

But the four days leading up to it weren’t peaceful at all.

Actually, it goes back even further, when a few months ago my father called and said he had stage 4 lung cancer. I was half surprised and half not because he had smoked for a good portion of his life (it helped keep him calm during the Vietnam War, and since then, it was something he truly enjoyed). But he had beaten prostate cancer a few years ago, and I knew he was a fighter. So when he told me the news yes, I cried, but I believed he would live much longer than the six-months-to-a-year that the doctors gave him.

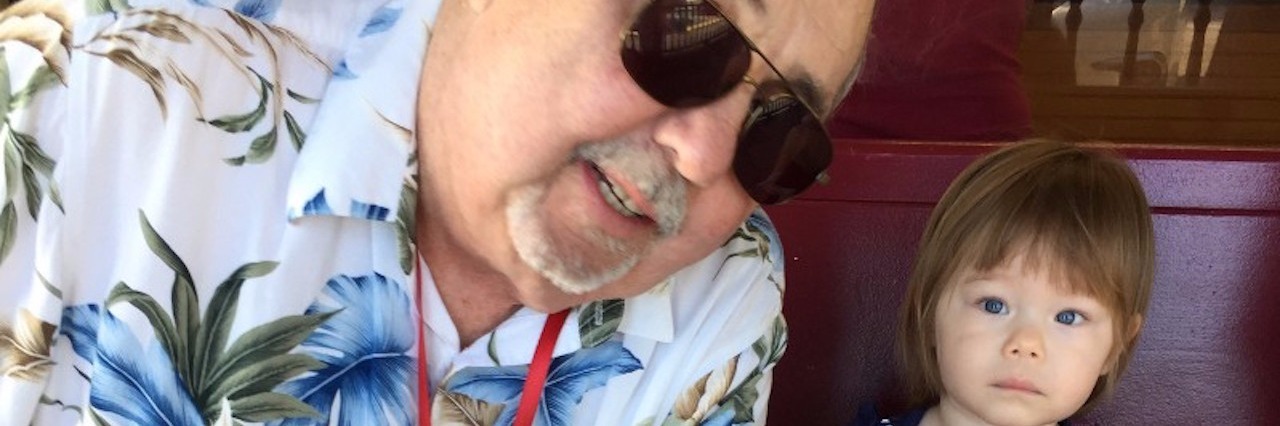

I started planning immediately when I would make the trip from Maryland to Oklahoma with my husband and my dad’s 17-month-old granddaughter. I wanted to do it as soon as possible because even though he beat the odds before, I had no idea just when or where this new cancer would take him.

My family made the trip to Oklahoma on the weekend of August 12. We only had about 36 hours with my dad and his wife, so we made the best of it, enjoying biscuits and gravy and visiting my grandmother (who met her great granddaughter for the first time). I sat next to him in his recliner, mostly in silence (neither of us were good at expressing our feelings), but there was a mutual respect and love between us that didn’t need words. As we drove away on Sunday morning to the airport, he smiled and waved goodbye, leaning on his red truck because his legs were weak. I managed to not cry until we pulled out of his neighborhood.

I was happy because I got to see him, and I was excited to plan my next trip to visit him. I would have to wait at least three weeks because he and his three best friends were doing a “guy’s trip” out to Colorado Springs. They rented a beautiful cabin right by the water, and all they wanted to do was fish, reminisce about the good old days and have peace and quiet.

Yes, the doctors told him not to go because the altitude would affect his breathing, and yes, his wife kept telling him not to go, but my dad refused. It was something he wanted to do, and he deserved to go to a place he loved with the people he cherished, one last time. He was supposed to start chemo on August 18, but he managed to put off the chemo treatments for two more weeks, until after he returned from his last fishing trip. He felt this was his one last hurrah before the treatment would break his body down even more.

The trip didn’t work out as planned.

The night after driving from Oklahoma to Colorado, and nine days after I last saw him, he was rushed to a nearby hospital because he had trouble breathing. He had to be air-lifted to a hospital with a lower altitude in Pueblo, Colorado.

I got the call from his wife Tuesday afternoon. She said the doctors had done everything they could to help him, but he wasn’t responding to any of the medication. There was nothing they could do. They would remove him from life support and would call when it was over.

My brother, sister and I all waited from our own homes on the east coast to get that call. It was hard not to be there, so we felt helpless.

Then I got a text from my sister that said, “he woke up.” I had to look at it three times. I didn’t believe it.

The ICU nurse said after they pulled the tubes, he started breathing on his own, and 25 minutes later he woke up mumbling for his wife. He told the doctors to do everything they could to bring him back because “they were coming for him.” We could only assume “they” were us, and he was right.

She said it was very unexpected, and she had never seen anything like it.

We scrambled to find flights to Oklahoma the next morning. Coming from Maryland, North Carolina and Florida, I was lucky to connect with my sister on a flight to Charlotte, and then we connected with my brother in Dallas. After about 10 hours flying and a 40-minute drive from the Colorado Springs airport, we finally arrived at Parkview Medical Center in Pueblo.

Walking into his room in the ICU wasn’t easy. Seeing the oxygen mask and all the machines hooked up to him made this once far-away dream a reality. Then the doctor spoke to us, making reality much clearer.

He said my father had high-altitude pulmonary edema. But due to my father’s condition at the time he arrived in South Fork, Colorado (altitude of 8,000 feet), his lungs were no longer able to breathe. He was airlifted to Pueblo (altitude of 5,000 feet) which is how he ended up at the ICU floor at the hospital in Pueblo.

At this point, the damage has already taken its toll, and there was nothing the doctors could do to treat my father. My father could not go back to the state he was in before his vacation trip started two days ago. He could no longer be treated with chemo or continue radiation once he got back to Oklahoma. The reality was that his death was imminent.

That’s what the doctor said directly to us and then to my father. “Your death is imminent. You can choose to be moved to hospice here in Pueblo or hospice in Tulsa. Either way, there’s no more treatment. But if you choose to go back home for hospice, you will not survive the transport.”

My sister remembers these exact words. She also remembers my dad’s reply as he hoarsely mumbled because of his fluid-filled lungs. His cancer had spread to his brain and spine two weeks prior, but the doctor in Pueblo said they confirmed it was now in his bone marrow.

“So die here or die in Oklahoma?” he said. We all heard it, and knew my dad understood exactly what was going to happen in the next few days or week.

As much as my father wanted to die in Oklahoma, moving him by air was out of the question, and transporting him to a hospice near his home in Oklahoma (if it was even possible) in 10 hours would likely kill him. Our only options were to keep him at the hospital in the comfort care cancer unit, or move him to hospice. Whatever was chosen, that would be where he would spend his final days.

We asked him what he wanted to do, and he said there was no decision to be made, that he will die in Pueblo at the hospice. He said, “Let’s go! What are we waiting on?” So his wife and my brother visited the hospice, and we planned to move him there the next day.

But dad always did what he wanted to, and this was no different.

Early Thursday morning, before we all arrived back in his room, he told the ICU main nurse that he did not want to be moved to the hospice. He would rather stay at the hospital to die because everyone had been so kind to him. The doctors and nurses smiled, and a few of them even had tears in their eyes. One doctor said he had heard how tough these Vietnam vets were, and my dad was proof of it.

My dad was moved down to comfort care on Thursday. It was a more spacious room, and much quieter on that floor, so I slept by his side, one night in a pullout and the next in a recliner. He could barely speak, but when he did, he asked for ice chips because that was all he could eat. I fed them to him, three at a time, so he wouldn’t choke. I would ask him if he was in pain, and when he said yes, the nurse on duty would come in and give him morphine. He would fall asleep, and then I would sleep a bit, but it would repeat every three hours.

Everything after Thursday was a blur, but what I do remember was the doctor coming in and saying that oxygen was the only thing keeping him alive, and that we should let him rest in peace. There was nothing we could do. I didn’t want to let him go, but in the middle of the sadness I found a sense of peace in knowing that he knew the people he loved, including his best friend, were right there with him.

Saturday at 7 a.m. they turned down his oxygen two levels. Then two hours after that it was another two. Two hours after that one. At noon his oxygen was turned off. At 1:20 p.m. on August 27, 2016 he took his last breath.

As I said, you never forget the moment you watch your father take his last breath. You never forget touching his arm, crying by his side, and watching his chest rise and fall, slower by the minute.

You never forget the silence in the room when it happens, or how people react differently to their own sense of sadness. Some choose to stay in the room, others walk away to be alone. There is no right or wrong way to react. You react because you care.

I know my father is now at peace, which gives me peace. He doesn’t have to endure countless hours of chemo, and he no longer has to stop and catch his breath when walking every few feet. He passed away going somewhere that he loved, surrounded by the people that he loved.

If there is anything I can take away from this physically and emotionally draining experience, it’s this: be at peace. Forget about what happened in the past, and forget about what could go wrong in the future. Find peace within yourself and with the people you love before it’s too late. Accept what life has given you, and challenge it to find your own happiness.

This post originally appeared on Medium.