Here's What You Should Know About Electroconvulsive Therapy for Your Mental Health

If there’s one mental health treatment with a lasting PR problem, it’s electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Once called shock therapy — though this isn’t really accurate — it was immortalized in the 1972 movie, “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.” Actor Jack Nicholson’s character undergoes ECT as punishment for being an unruly patient, and the visual representation of ECT left a lasting impression.

Mental health treatment in the 1950s, the era depicted in the movie, is associated with other crude and often cruel strategies like lobotomies and insulin shock therapy. While most of these practices have been discontinued, ECT endures. With some safety modifications thanks to modern medicine, it’s one of the most effective treatments for serious mental illness, including treatment-resistant depression, bipolar disorder, severe schizophrenia and catatonia.

What Is ECT?

ECT is a medical treatment that induces a seizure after electrical current passes through the brain to decrease mental health symptoms. ECT’s colorful history can be traced back to 1938. Earlier in the 1930s, Hungarian psychiatrist Ladislas von Meduna theorized that inducing seizures may cure schizophrenia.

He developed a chemical method to do this — a reportedly terrifying experience for patients — that seemed to reduce psychotic symptoms. Building on Meduna’s work, Italian psychiatrists Ugo Cerletti and Lucio Bini discovered they could use electricity to cause seizures instead, and ECT was born.

In the 1940s, doctors realized sedation with barbiturates could make ECT more comfortable. By 1949 psychiatrists learned to place electric currents to avoid speech areas of the brain. However, ECT still had a dark side. In mental health hospitals, ECT was sometimes used as a punishment to control patients as depicted in Ken Kesey’s book and later the movie, “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.” With the discovery of psychiatric medications and rise of the anti-psychiatry movement in the 1960s and ’70s, ECT fell out of favor.

Today, an estimated 100,000 people receive ECT treatments each year, though it could be more. This is an older statistic and it’s hard to collect accurate data because ECT isn’t well tracked. In addition, those who may benefit most from ECT usually live with a more severe mental illness that prevents them from giving informed consent to participate in research. Scientists also don’t really understand how or why ECT works. This may sound alarming, but we don’t have any idea how psychiatric medications really work either.

“Frankly we know as much and as little about how ECT works as we know about how any of these medications work,” Richard D. Weiner, M.D., Ph.D., professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University School of Medicine, told The Mighty. “The same brain neurotransmitters, the chemicals that are used within the brain to communicate among the brain cells, the neurons — [ECT] does the same thing to those as any antidepressant medications do but it does it more powerfully.”

Who Should Get ECT?

Despite not knowing how it works, it’s clear that for some people with a mental illness, ECT is incredibly effective. It could be the most effective treatment for depression we have. Studies show that 60 to 90 percent of those who receive ECT respond, compared to an estimated 40 to 60 percent response rate with antidepressants. Weiner estimates that about 80 percent of those who get ECT are treated for a major depressive episode.

ECT isn’t just recommended for severe, often treatment-resistant depression. It’s also been helpful for some who experience mania or even hypomania with bipolar disorder. One study found that nearly 70 percent of participants with bipolar disorder responded to ECT treatment. ECT’s other use, which dates back to the beginning, is for severe schizophrenia. In researching ECT for those with schizophrenia, doctors found 77 percent of study participants responded.

Research also suggests that when you have more serious mental illness symptoms, you’re likely to respond better to ECT. Those who experience psychosis and delusions with depression, for example, enter remission from their symptoms an estimated 80 percent of the time compared to those who left their symptoms untreated. Treatment can also reduce catatonia, a state when you become unresponsive, sometimes lying in one place for days, which can cause physical complications if left untreated.

Though ECT might outperform psychiatric medications in studies, it’s not used as a first-line treatment. Weiner said he doesn’t usually recommend it as a second-line treatment either. Partly because of its controversial history and also because of its risks and side effects. (More on this later.) You may come to ECT as a last resort when you’ve already tried countless combinations of medications to little or no effect.

What It’s Like to Get ECT

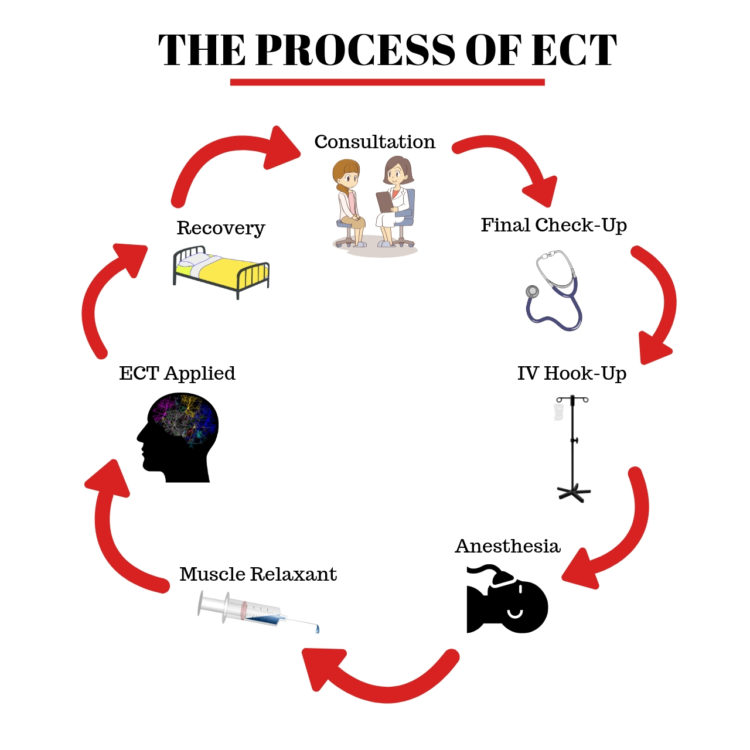

The first thing you can expect is a consultation with a doctor. They’ll talk to you about the potential risks, benefits and side effects, as well as what to expect. Before you start ECT, your doctor should evaluate you and your blood levels to make sure you can safely undergo anesthesia.

Typically you will start with a series of six to 12 ECT sessions that are done two or three times per week. Each ECT session takes about an hour, which includes anesthesia, the ECT treatment itself and a short recovery time. The only part of the process that hurts, according to Weiner, is when they insert the IV line before starting treatment. And, unlike in the old days, you can decide to stop ECT at any time.

“If we’re recommending ECT, the patient’s in control. We’re just making a recommendation,” Weiner emphasized. “Even though it’s a series of treatments, they can stop at any time and we tell them that.”

When you first arrive, a nurse will check your vital signs like your heart rate and blood pressure. After this, your doctor may come and check on you to review one more time whether or not you’ll be getting treatment that day. Then you’ll be hooked up to an IV line. An anesthesiologist will give you fast-acting anesthesia through the IV line that works in about a minute. You’re asleep during the rest of the procedure.

Once the anesthesia kicks in, you’ll be given a muscle relaxant to prevent your body and muscles from moving during the seizure, which makes the procedure safer. It’s also important because when your muscles are convulsing, your system uses up a lot of glucose and oxygen, which doctors want to avoid. During ECT, you will be given oxygen and your heart rate and blood pressure will be monitored to make sure you’re safe.

If it’s your first time getting ECT, the doctor will determine the amount of electricity that’s appropriate. The electricity is applied to your head through electrodes placed on your scalp. Keep in mind the electricity used for ECT isn’t the same as what comes out of a wall socket — it mirrors the level and type of electricity that occurs naturally in your brain.

You may receive electrical currents that are either unilateral (given to only half of the brain) or bilateral (given to the whole brain). Once the doctor applies the electricity, you will have a seizure that lasts a minute or less. Then you’re taken to recovery for around 30 minutes when the anesthesia wears off.

Should You Get ECT?

ECT is a statistically safe treatment. Research shows it’s the lowest risk medical procedure that involves general anesthesia. In a study looking at more than 73,000 ECT treatments given at Veterans Administration hospitals between 1999 and 2010, there were no deaths recorded and few serious adverse events. Despite its reputation, ECT does not damage the brain.

“There is no evidence that ECT damages people’s brain,” Weiner said. “There’ve been plenty of studies on that, particularly recent studies, that have looked at things much, much more carefully and rigorously than the old, old studies, which really were not valid at all.”

For some people, the damage depression can do to your brain might be the bigger cause for concern. “ECT actually may be good for your brain in terms of the nerve cells,” Weiner added. “The depression that’s being treated is bad for your brain. Recent studies have found that these brain abnormalities are reversed when the depression is successfully treated.”

As you and your doctor decide whether ECT might be a useful treatment, you’ll need to weigh the risks and benefits carefully. Sometimes it can even be the choice between two difficult options that both seem less than ideal. Weiner explained how he navigates this balancing act:

Say somebody is high-risk if somebody did the treatment. But if one didn’t do the treatment, the risk of not doing it and having them stay as sick as they were is even higher, then it’s actually safer to do the one with the lower risk. It’s like somebody that has a severe medical illness and the physicians come and say, ‘Well, you need this surgery or you’re going to die or become much more ill and the surgery is risky, but if we don’t do it, the situation’s going to be even worse.’

Risks Associated With ECT

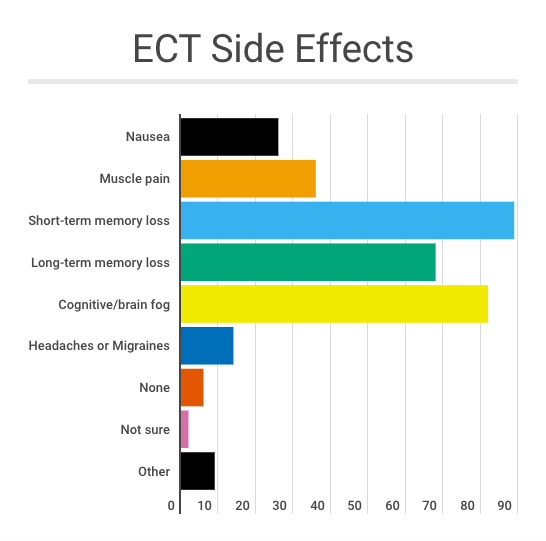

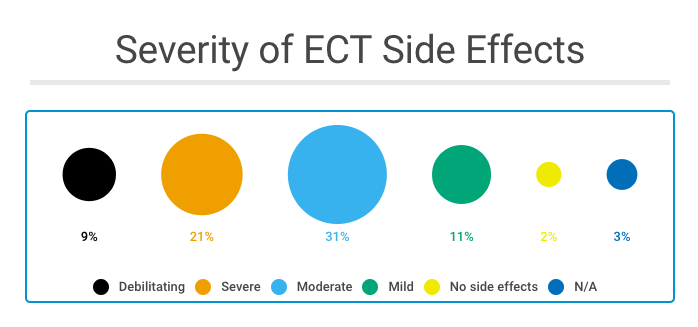

Like other medical treatments, ECT can cause several side effects that range in severity. We surveyed the Mighty community, and of the 110 people who had ECT and answered our survey, the most commonly reported side effects were headaches or migraine, nausea, muscle pain, brain fog and short- or long-term memory loss.

The Mighty community rated the severity of their side effects following treatment most often as moderate (31 percent of participants) or severe (21 percent of respondents). Only 9 percent said their side effects were debilitating while 13 percent said the effects of ECT were mild or non-existent.

Memory and ECT

Perhaps the biggest risk factor and most debated side effect of ECT is its impact on memory. ECT can cause anterograde amnesia, difficulty remembering new information, or retrograde amnesia, trouble remembering information from the past. In general, ECT has been found to most affect your recent memories, but everyone’s experience is different, from severe to little memory loss.

“ECT saved me from non-stop feelings of depression and suicidal thoughts,” Mighty community member Ashley Owens said. “I had memory loss of events that happened right around a treatment, such as seeing a movie. Other than that, my memory seems pretty well intact.”

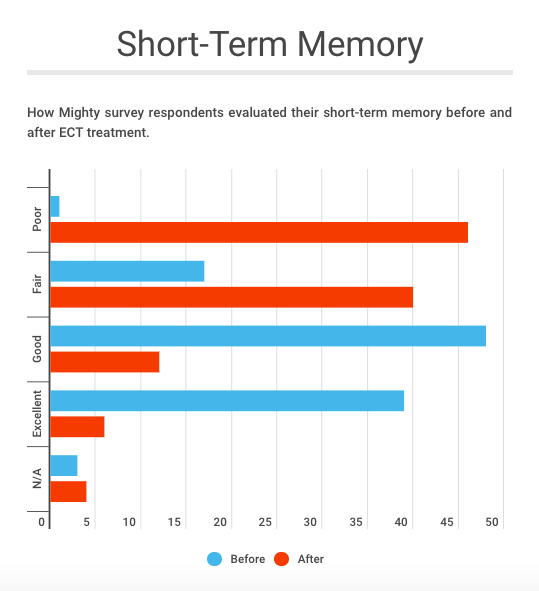

When we surveyed The Mighty community about their experience with long- and short-term memory following ECT, memory loss was a significant concern. While 81 percent of those who responded to the survey said their short-term memory was good or excellent before ECT, only 17 percent rated their memory as good or excellent following ECT.

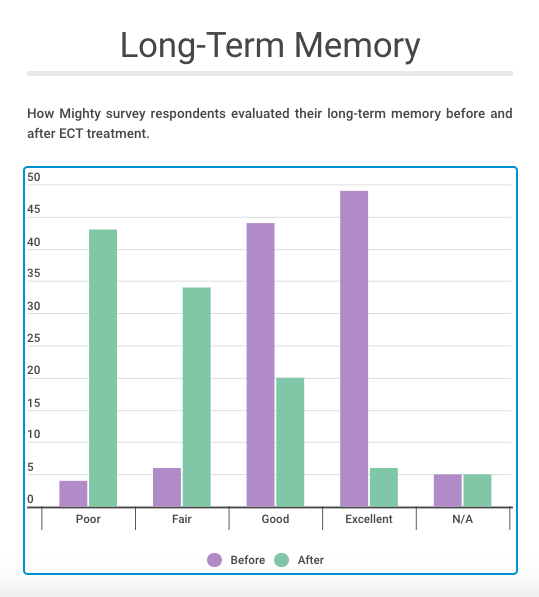

The results were similar when we asked the Mighty community about long-term memory. Only 4 percent of survey respondents rated their long-term memory as poor before ECT. After ECT, 40 percent rated their long-term memory as poor. Only 24 percent said their long-term memory was good or excellent after ECT, compared to 86 percent before ECT.

“I forgot so much … including a lot of my son’s first year, my grandmother’s funeral, etc., and I still have a hard time with short-term memory and there are a lot of long-term memories that I’ll probably never get back,” a Mighty survey respondent wrote. “I also had to quit my job because I had started it just a few months before ECT and when I went back afterward there was so much I couldn’t remember how to do.”

Though memory loss is clearly a concern among patients, psychiatrists seem to give memory loss a lower priority in whether or not a patient should undergo treatment. An article in Psychiatric Times suggests that “the concern about cognitive effects is exaggerated; most ECT patients experience minor cognitive impairment, much of which is temporary.”

The articles goes on to explain that memory loss isn’t a safety issue but a tolerability issue, the same way that those with cancer “tolerate” the side effects of chemotherapy. In other words, the side effects of ECT, like chemotherapy, are unpleasant but something that can be tolerated. However, memory is inherently linked to who we are and what makes life meaningful. Memory loss may not be experienced as just intolerable — it can be perceived as an erasure of the very pillars of our identity. One Mighty survey respondent explained how this felt:

It freaked me out that I no longer could remember basic things and made me afraid I could never practice law again. I felt suicidal and didn’t know who I was anymore. The memory problem lasted longer than expected — over 3 months. I felt like I couldn’t trust myself to drive or do any activities of daily life. I had to wear my glasses on a cable around my neck and keep a notebook to tell me what I was doing, planning to do and had done. The worst was losing my identity and becoming so hopeless I was suicidal.

If memory loss is a serious concern for you, talk to your doctor. There are ways to minimize the impact of ECT on your memory. For example, you might spread your treatments out from three a week to two a week. Or, your doctor can change how and where they place the electrical stimulus so it’s moving through different areas of your brain. Check in with your doctor after each treatment, because generally memory loss is cumulative — Weiner said one treatment won’t cause significant memory loss.

Some evidence suggests that memories may not be lost after ECT, they’re just not as easily accessible. Weiner said he’s seen that when people who have experienced memory loss due to ECT are re-taught something they forgot, “they learn it much quicker, indicating that the memory actually is there it just doesn’t connect up with consciousness.” For a small minority of patients, ECT could even help your memory.

“Some patients actually feel that ECT helps their memory,” Weiner said. “One of the things that happens in patients who have severe depression is their mind isn’t functioning. They can’t process information, they can’t remember things and when the depression is relieved, whether it’s by ECT or medications or whatever, they can remember things again.”

Benefits of ECT

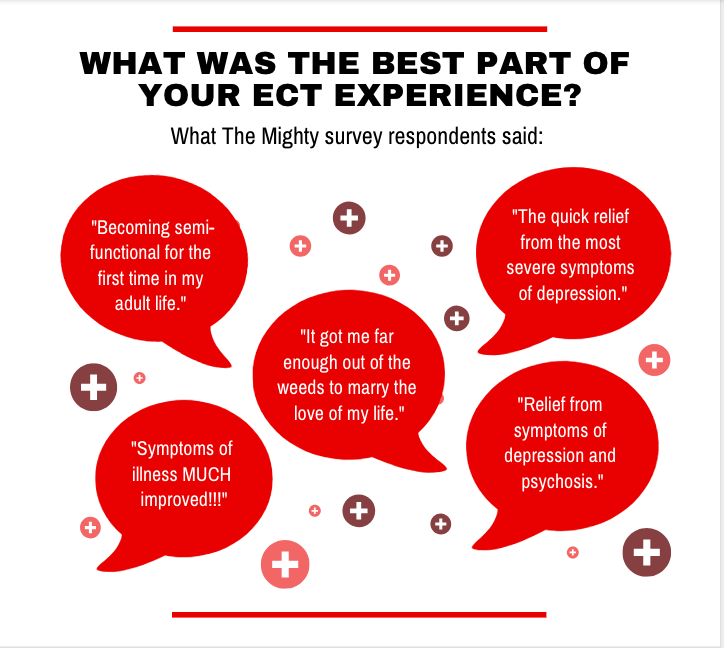

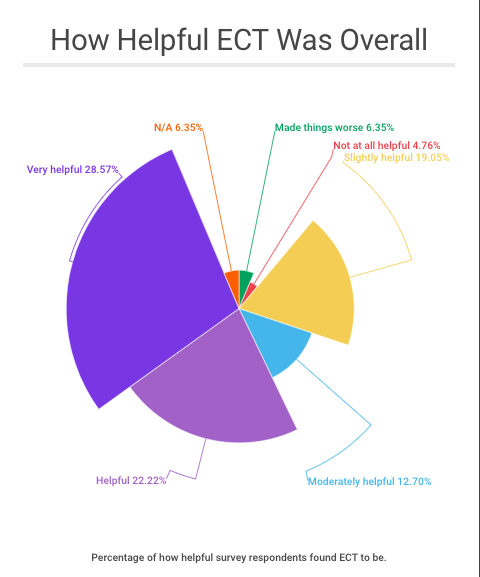

The side effects of ECT may sound scary, but the truth is if you live with treatment-resistant or severe mental illness, ECT can have a major, positive effect.

Of those who had ECT and responded to The Mighty’s survey, 45 percent reported ECT helped them feel better at some point during their treatments compared to 40 percent who did not find ECT made them feel better. Another 15 percent were unsure if ECT helped. Overall, 50 percent of those surveyed said ECT was helpful or very helpful overall, and only 11 percent stated that ECT was either not useful at all or it made things worse.

“I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that ECT saved my life,” Mighty community member Michelle Kolterman wrote. “Multiple suicide attempts and unending hospitalization cycles were the norm. After many treatments and maintenance, ECT I have had some wonderful years. Yes, it is unnerving to have memory gaps but my illness causes those problems too. Not a treatment for everyone but I would undergo it again if the depression flares up.”

Header image via Jolygon/Getty Images.