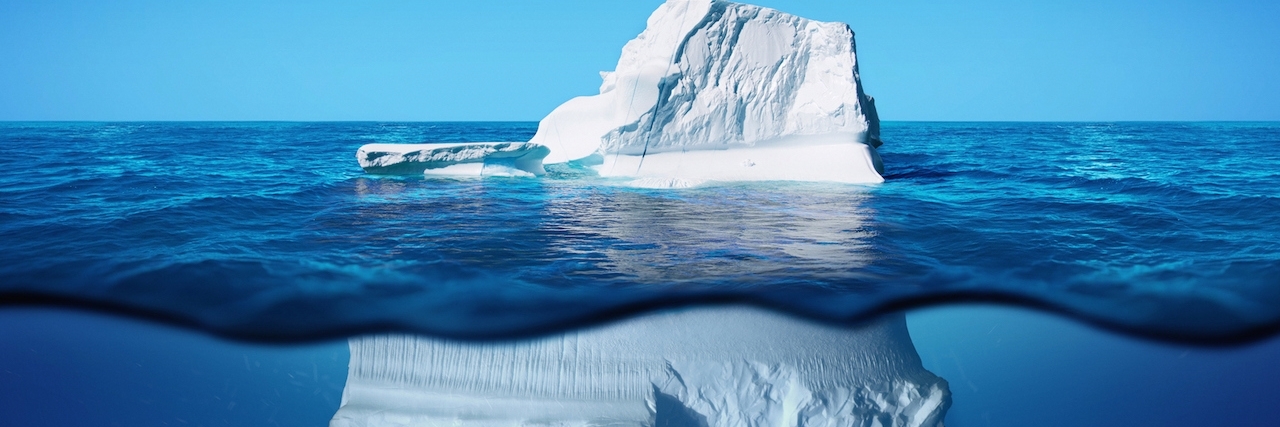

Chronic illness and icebergs: what do these two things have in common for me?

First, my realization that narcolepsy had turned into this cold, lonely and heavy weight attached to me. And second, there’s a whole lot I don’t want others to see in regards to how much I’m struggling with this darn thing.

At my follow-up appointment with a new neurologist in February, I told him that while I had thought a regular routine and schedule would reduce my symptoms, I was moving in the opposite direction the farther I got in my 40-hour-a-week internship. I was looking for help — I told him I want to be working, I want to be doing something I love, and I asked for more behavioral-type coping skills I could do, a change in medication, something. I just wanted to be better, because even at this point, I could see what I was doing would not be sustainable in the long term.

What I got out of his response was that he wanted to help me, but I had to remember that %%usNFh1yFTq%% is a lifelong condition and I essentially may be as good as I can get. Oh, and if I thought seeing a therapist would help, he would give me a referral to a therapist, if I found one for him.

The gravity of “chronic” suddenly hit me, and I left that appointment in a slow fog. Literally, because I was having to avoid any emotion and count my steps to keep myself moving to the car, and dragging this big ‘ol iceberg was not helping.

1, 2, 3, 4. 1, 2, 3, 4.

When my thoughts drifted from counting, I’d feel the familiar buckle and wobble in my knees. I took the elevator instead of the single flight of stairs, and the normally three-minute walk from the checkout desk to my car took closer to 10. When I finally made it into my car, something great happened: I broke down. I melted, cried and cursed and hiccuped and wallowed in my self-pity for a good 20 minutes.

Why was this great? I hadn’t been able to cry for over a month because the emotion that comes along with tears and puffy eyes was apparently too much for my cataplectic body to handle, and whenever I would come close, I’d wilt into “numbness” as I call it (cataplexy). Basically, I’ve got no emotion (or movement) for however long my body decides it needs. Might be 10 minutes, might be two hours.

Either way, I give no sh*ts about anybody or anything during this time, which one might think is good, but you’re just avoiding the problem, and so it keeps building under the surface. Each time I tried to address it, my body was like, “Nope. Can’t handle. Time out.” I’ve been building an iceberg, and maybe I chip off a chunk or sweat a few drops when the sun is particularly strong, but I’m still sitting in the Arctic. Each time I couldn’t deal with what was happening to me, the submerged part got a little bigger and a lot heavier; all these emotions to deal with, and my own condition was suppressing them.

Now, bear with me, because I love metaphors for explaining concepts, and also, I learned a lot about icebergs during this. Takeaway: icebergs are super interesting.

So, when you have turned into an iceberg, how does one expose the 90 percent of you chilling underwater?

The answer is, you don’t. Well, technically you could if you can flip the iceberg over. However, I would not suggest that seeing as 1) it takes a whole lot of work; 2) it can release the same amount of energy as an atomic bomb (what the hell?); and 3) you’re still going to end up with a majority of that thing underwater.

But for a long time, that’s what I’ve been trying to do. Flip the iceberg. I thought if I could just try a little harder, accomplish one more thing, or go just a little longer acting like I wasn’t as tired as I felt, I could flip this and get myself back.

I don’t think it’s going to work like that for me, though. I don’t need to flip the iceberg — I need not to be an iceberg.

You know what an iceberg normally does? It just goes along its merry way, floating through the ocean, soaking up some sun, riding the waves and generally moving toward warmer waters. And as it does, it gets bopped around, loses a piece here or there and melts until it’s a harmless nugget called a growler, and eventually it’ll completely melt. It’s still water, no matter what it looks like, so to me, melting is fine in this situation. (Note: I am not OK with climate change and global warming — giant glaciers melting and falling into the ocean and such, not cool. Tiny hunk of ice just doing its thing, OK.)

What I’m saying is, I’m done fighting and building my big, cold %%SR8Vq5QSeG%% iceberg. Acting like I’m OK and getting better when I’m not (yet) is only more draining for me in the long-term. I’m trying to undo over two years of chronic sleep deprivation, so that requires some patience. But instead of putting up the facade I’ve perfected, I’m finally allowing myself to just be “sick.”

Of course, there are instances when this isn’t feasible, but for the most part, I’m trying to feel what I feel. It’s not going to be easy, because I am normally an active and on-the-go kind of gal, but the truth is, I am a whole lot of tired, a whole lot of time. I’m going to try and think of this time like I’m stopping to smell the roses (or take a nap at the roses, whatever), see what opportunities I can find with my slow journey, and trust that the current is moving me toward warmer waters.

Moral of the story: I’m learning when to fight, and when to float.

Follow this journey on Rec. Sleep. Ride.

The Mighty is asking the following: Coin a term to describe a symptom, characteristic, aspect, etc., of your diagnosis. Then, explain what that experience feels like for you. Check out our Submit a Story page for more about our submission guidelines.