OCD: From Memoirs to Big Screen, Misunderstood Mental Illness Finally Gets Its Due

Editor's Note

This story was originally published by MindSite News and is republished with permission.

By Sarah Henry

“I have thought spirals I can’t control,” explains a participant on “You Can’t Ask That,” an Australian TV series exploring what it’s like to live with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). “It’s with you every single moment of every single day – I have OCD in my dreams,” another responds. Says a third: “The voices are never satisfied, no matter how much effort you put in. You can never win.”

OCD is relentless. While the disorder varies from person to person, most of those affected have intrusive negative thoughts (obsessions) and have developed coping mechanisms—repetitive behaviors (compulsions) such as checking locks, tapping fingers, counting, and hand washing to try to keep doom at bay. Many have dual diagnoses: The show’s OCD sufferers discuss dealing with anxiety, depression, panic attacks, compulsive gambling, substance use addiction, Tourette syndrome, and trichotillomania, or hair-pulling disorder. Several on the show say they have contemplated suicide. “I wanted to make it stop permanently,” explained one. “I thought it was the kindest thing I could do for myself and everyone around me.”

Welcome to the debilitating, exhausting world of OCD. On the thought-provoking Australian TV series, people with the disorder answer often outrageous and uncomfortable questions posed by anonymous members of the public as a way to debunk myths and stereotypes. (An American version of the popular program – which, like the original, will feature episodes on other marginalized groups as well – is in the works.)

The series is intended to educate and entertain with compassion, kindness, and wit. An episode in season 6 explored a range of experiences for people living with OCD – from people who hoard or fear contaminating others, to those who admit to crimes they didn’t commit or brood incessantly about everything from having sex to climate change. Sufferers try to soothe their “sick brains” and frightening ruminations through repetitive rituals, even as their logical minds know their thoughts and actions are illogical.

Despite the clichés in popular culture, not everyone with OCD is a neat freak, organizing guru, or excessive hand washer. Thankfully, more nuanced representations of what it really means to live with OCD are popping up on the screen and in books. (More on that later.) Some of the questions posed to the participants on “You Can’t Ask That” reveal the depth of ignorance among the general public, with questions such as: “Are you sure you have OCD? Maybe you’re just anal.” Or: “Don’t you realize what you’re doing is irrational and crazy?” And: “Why don’t you try to fix it with something chill like yoga?”

The participants address these questions with honesty, sincerity, and a sense of humor. They’ve learned to live with and accept the chronic condition and have gotten assistance – both therapeutic and pharmaceutical – to help manage their OCD. “This is the brain I was born with,” says one, who has made his peace with the disorder. “This is what I’ve got.”

OCD as pop culture punchline

In the United States, OCD has long been played for punchlines in pop culture. On television shows in particular, the person with OCD is mocked for their quirks, and is poorly defined and misunderstood. OCD and the people who suffer with it are cast as caricatures: the germaphobe who won’t stop washing their hands or the anti-clutter crusader who craves a well-curated space and is more organized than Marie Kondo. Think Monica on “Friends” or Sheldon on “The Big Bang Theory.”

But Monica’s domestic perfectionism doesn’t cause major distress or brain chatter, so by the benchmarks set by the DSM-5, the American Psychiatric Association manual and a resource mental health professionals use for diagnosis, Monica does not have OCD. Similarly Sheldon is obsessed with order – where he sits, what he eats, knocking in a pattern on friends’ doors – but these behaviors don’t consume him or impair his work and social life.

If anything, these two characters exhibit signs of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD), which is similar to – though not the same – as OCD. OCPD may have cultural or environmental triggers and does not include intrusive thoughts. People with OCPD often have an overwhelming need for rules, regulations, routines, lists, and schedules.

In contrast, actor Lena Dunham, who actually has OCD, gets it right in her portrayal of Hannah on “Girls,” according to both people with OCD and professionals who treat them. Hannah tries to manage her unrelenting anxiety and unwanted thoughts by doing things in increments of eight: opening the door eight times, eating eight chips. In the HBO teen hit “Euphoria”, the lead character counts ceiling tiles as a way to self-calm.

In March 2022, Amy Schumer, the writer/director/star of Hulu’s“Life & Beth,” gave an accurate, respectful portrayal of trichotillomania, which she struggles with in real life. Schumer described it as a shameful secret which once required her to wear a wig to school because she had plucked out so much hair.

I used to think my brain was my enemy, but now I think of it with fond exasperation. It’s unquestionably a pest. It is. I wish it behaved better. But I also never forget that it makes me who I am.”

— Author and artist Sangu Mandanna, discussing her OCD

Still, inaccurate representations are also common. In 2018, Khloe Kardashian launched the “KhlO-C-D” social media campaign: In one video Kardashian takes followers into her meticulously organized pantry, with its neatly labeled containers (shout-out to brands to boot). “You say OCD is a disease, but I say it’s a blessing,” said Kardashian.

Kardashian faced a backlash from fans and OCD sufferers for trying to monetize a mental disorder. For people with OCD, it’s not a joke, it’s a source of despair. “I went three months without using my stove, reasoning that, if I never turned it on, then I didn’t have to worry about checking it,” wrote Lisa Whittington-Hill in an eloquent essay on OCD’s toll. “If food needed to be heated, I microwaved it or used boiling water from a kettle, or else I didn’t eat it at all. That lasted until I began to think about checking the microwave and kettle, at which point I switched to sandwiches and cereal. My OCD has cost me so many moments and opportunities.”

For many with the disorder, cleanliness and order isn’t a factor at all. “Anyone who has OCD would agree that they wish it was just a lovely illness that makes their house impeccably dusted,” wrote one columnist who was offended by Kardashian’s campaign. “Instead it leaves sufferers on edge, exhausted, and struggling to do day-to-day tasks as they do whatever compulsions they can to quiet their minds.”

The ABCs of OCD

Participants in “You Can’t Ask That” reveal the intrusive, unwanted, and sometimes violent thoughts and urges that barge into their minds and resist their efforts to make them go away, taking up residence in their brains like an endlessly looping record on repeat, wreaking havoc on their lives. OCD is a constant companion, though it can wax and wane.

Most people have occasional obsessive thoughts or compulsive behaviors but for people with OCD, these symptoms generally last more than an hour each day. Symptoms typically begin anywhere from childhood to young adulthood. About 1 in 100 Americans have OCD, according to the International OCD Foundation – about 2 to 3 million people in the U.S. Some sufferers can go decades before receiving a diagnosis and getting help. The World Health Organization ranks OCD as one of the 10 most handicapping conditions by lost income and decreased quality of life.

Consider humorist and author David Sedaris. In “A Plague of Tics,” from his essay collection, Naked, Sedaris recounts the obsessive-compulsive behavior that dogged his childhood. A voice in Sedaris’s head told him to repeatedly lick light switches, kiss the carpet, tap his forehead with the heel of his shoe, press his nose against windows, and other socially frowned upon repetitive behaviors. Sedaris couldn’t escape the cyclical orders in his mind. “There must have been an off switch somewhere,” he wrote, “but I was damned if I could find it.”

As a young adult, Sedaris began smoking and found his compulsions began to fade. “Maybe it was coincidental, or perhaps the tics retreated in the face of an adversary that, despite its health risks, is much more socially acceptable than crying out in tiny voices,” he wrote in Naked. “Everything’s fine as long as I know there’s a cigarette in my immediate future. The people who ask me not to smoke in their cars have no idea what they’re in for.”

These days, he no longer smokes and is an obsessive walker and roadside litter collector, sometimes spending eight or nine hours a day collecting trash near his home in England, where a garbage truck is named in his honor.

As Sedaris suggests, OCD is not well understood. Researchers suspect unusual activity in portions of the brain that help regulate urges are responsible. These areas may not respond typically to serotonin, a chemical that nerve cells use to communicate with each other and signal to the brain that impulses have been sated. Instead, a part of the brain that is designed to protect by warning of imminent danger is triggered and gets stuck. People with OCD often exhibit a heightened sense of responsibility or obligation around protecting themselves and others.

ERP therapy “was one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do, but not as hard as living for 20 OCD-riddled years without help. It rescued me.”

— OCD Blogger Jackie Lea Sommers

Genetics are thought to play a significant role. If a parent or sibling has OCD, there’s a 25% chance of having the disorder. While it’s considered chronic, treatments can help. Some sufferers report improvements with exposure and response prevention (ERP) therapy or psychiatric drugs, particularly serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SRIs, a class of antidepressants that includes selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs.

ERP guides OCD sufferers to expose themselves to things they fear, and then practice keeping compulsions in check. “It was one of the hardest things I have ever had to do—but not as hard as living for 20 OCD-riddled years without help. I hated to go through ERP, but I love that I have gone through it,” wrote Jackie Lea Sommers, who blogs about living with OCD. “It rescued me…I can only wish I’d experienced it earlier.”

YA fiction explores what it means to live with OCD

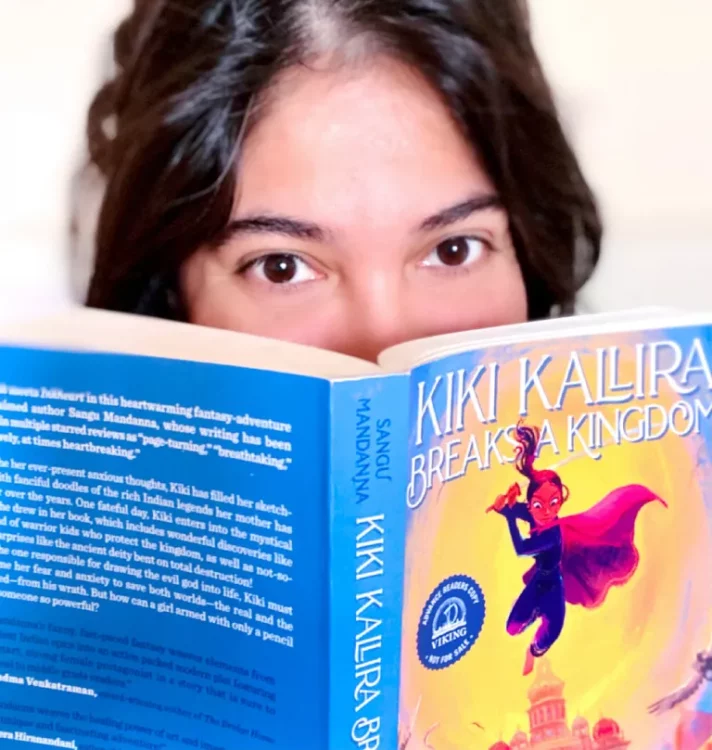

Sangu Mandanna peers over the cover of her sci-fi fantasy novel about a girl with OCD. (Image courtesy of the author.)

A growing list of novels aimed at young adults explores what it means to live with OCD, including Kiki Kallira Breaks a Kingdom, The Weight of Our Sky, Waiting for Fitz, and The Unlikely Hero of Room 138. In another YA novel — Kissing Doorknobs by Terry Spencer Hesser — protagonist Tara lives in fear that unless she performs time-sapping rituals every day, the people she loves will die. “I didn’t really understand OCD, but I thought I did,” wrote one reader on Amazon. “I asked my granddaughter how much she identified with the subject of the book. Her answer was 90%! This book has helped me to understand, to provide support, and to eliminate impatience.” And in a review of a dozen YA books featuring characters with OCD, writer CJ Connor wrote: “I felt so much less alone and ashamed of my condition after encountering a narrator who understood what I was going through.”

Contamination is a common theme. Lucy, the lead character in The Miscalculations of Lightning Girl by Stacy McNulty, is a middle school student whose OCD manifests in a need to repeatedly toggle between sitting and standing to prevent the digits of pi from taking over her brain like some kind of mathematical infection. She also fears germs, prompting a fellow student to call her the “cleaning lady,” because Lucy cleans everything she touches with sanitizing wipes.

Perhaps the best-known YA novel about OCD is Turtles All the Way Down, by John Green, a bestselling author who also has the disorder. His lead character, Aza, ruminates on breeding harmful microbes and contracting a bacterial infection. She constantly reopens a self-inflicted cut on her finger to drain and clean it, getting fleeting relief from the stress of imagining the bacteria seeping into her body. Aza is stuck in a thought spiral that never ends; it just keeps tightening, infinitely.

Green’s own OCD has sometimes been crippling. On NPR, he described his thought spirals – largely focused on contamination – as an invasive weed that hijacks his consciousness for days, weeks, or months. Though he worried that writing about it might trigger an attack of the disorder, he was determined to write what he knows and share it in an honest and authentic way.

“I want to talk about it, and not feel any embarrassment or shame,” he told the New York Times, “because I think it’s important for people to hear from adults who have good fulfilling lives and manage chronic mental illness as part of those good fulfilling lives.” He says on a video: “There is hope even if your brain tells you there isn’t.”

Green was about 6 when he became aware of his obsessive thought patterns. He was afraid his food was contaminated, and would only eat certain foods at particular times of day. As an adult, he has mostly kept his anxiety in check, with a mix of medication and cognitive behavioral therapy. From time to time, though, uncontrollable thoughts still overwhelm him. Writing provides some relief, though at his sickest he’s unable to think coherently enough to write. “I don’t feel like my mental illness has any superpower side effects,” says Green, who resists urges to stigmatize or romanticize OCD.

Turtles All The Way Down is set to be adapted as an HBO movie, with Isabela Merced playing Aza.

Sangu Mandanna (Image courtesy of the author.)

Across the Atlantic, British author Sangu Mandanna describes her mind as “a menace,” in a post for School Library Journal. Like her character in Kiki Kallira Breaks a Kingdom, she is neurodivergent and has OCD, anxiety, and depression. She was about 11 – the same age as her lead character – when her own OCD began. “The thing I remember most about it was how guilty and ashamed I felt,” Mandanna wrote. “I didn’t know what it was, or why my brain was doing these things, so I was so sure for a very long time that there was something wrong with me.”

She has come a long way since then. “I know now, of course, that there’s nothing wrong with me,” she wrote. “I have a mental illness. My OCD, depression and anxiety may never go away, but they can be treated, and I no longer feel any sense of shame or guilt about them… I used to think my brain was my enemy, but now I think of it with fond exasperation. It’s unquestionably a pest. It is. I wish it behaved better. But I also never forget that it makes me who I am.”

If you or someone you know is having suicidal thoughts, call 911. Or call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741. En Español: 1-888-628-9454; Deaf and Hard of Hearing: 1-800-799-4889.

If you or someone you know experiences hair-pulling disorder, the TLC Foundation for Body-Focused Repetitive Behaviors offers support and resources.

Lead photo via ABC TV & iview/ YouTube