In many ways, my family is an average American family. I work in healthcare and my husband Jake is a veteran who now works in the oil and gas industry. We have two energetic and beautiful sons, Remington and Braxton, and a beautiful home in Casper, Wyoming where we are surrounded by friends. But if you take a closer inside look, especially at our grocery bill, you see that our family is anything but average.

- One box of low protein pasta- $12.00

- One and a half pounds of low protein burger patty mix- $30.49

- Six low protein hot dog buns- $12.00

- Loaf of low protein bread- $14.49

Our family turned upside down four days after Braxton was born. A nurse called and told us the results of Braxton’s standard newborn genetic screening test — our seemingly healthy baby had phenylketonuria (PKU), a rare inherited metabolic disorder. If levels of phenylalanine in his body are not constantly managed, Braxton could be at risk for behavioral problems, seizures, and severe intellectual disability.

Nothing can prepare you to hear that your newborn will need to live with, and manage, a rare disease that not many people have heard of before. Since that day, our family has done hours of research, spoken with many physicians, and absorbed as much information as possible about PKU to ensure that Braxton has access to the resources and care he needs for the rest of his life. I have personally worked to build broader awareness of the disease and have become an advocate for the Medical Nutrition Equity Act (HR 3783/S 2013), speaking to Wyoming’s legislative representatives about the importance of this bill, which would require public and private health insurance companies to cover the cost of formulas and medical foods that people with phenylketonuria and other metabolic and digestive disorders need.

Phenylketonuria is caused by a genetic defect that impacts the function of an important enzyme in the body that enables the breakdown of phenylalanine (Phe), an amino acid found in many foods including meats, breads, cereals and some vegetables. Phe levels in healthy infants are two milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL) or less. When Braxton’s levels were first tested, they were about 29 mg/dL — that’s more than 10 times normal! Most PKU patients are advised to adhere to a strict, low-protein diet and metabolic formula, which they must maintain for their entire lives. If Braxton does not follow this diet, the consequences for him could be severe.

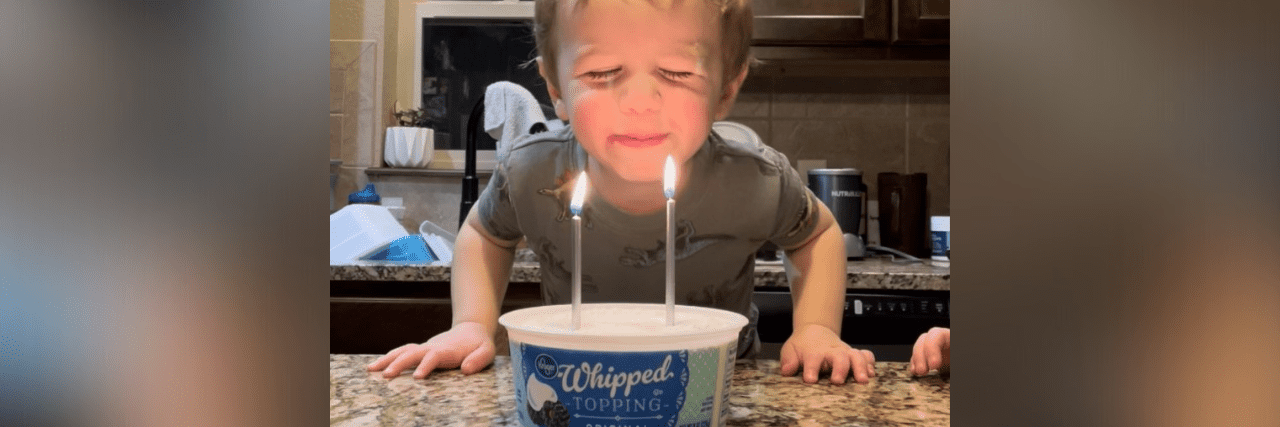

Keeping Braxton on a low-protein diet that is also healthy and nutritious has proven to be an almost impossible challenge from day one. When he was a newborn, we worked with metabolic specialists to determine the right balance of medical formula and breastmilk he needed to develop properly while keeping his Phe levels at a minimum. When he got older and began eating solid foods, it was a nightmare. It seemed like protein was in everything. Kid-friendly staple foods like bread, eggs, cheese, pasta, and chicken nuggets were, and continue to be, off-limits to Braxton. Even foods that the average person might think are low protein such as french fries have to be carefully measured and limited because of the small amounts of protein they contain. The only way Braxton can experience most of the foods an average person eats is if I order him modified versions of pastas, breads, and meat replacements from medical food companies. The cost of these specialty foods is often exponentially higher than their “normal” counterparts. I spend most of my days trying to find ways to make Braxton’s food look and taste like the food the rest of our family eats—I never want him to feel different or left out because of phenylketonuria.

As promising research continues for new and much needed treatment options for phenylketonuria, especially for those for whom current treatment options are inadequate or ineffective, I am dedicated to ensuring that Braxton and others like him have access to the resources they need to stay as healthy as possible. Many families impacted by PKU are struggling financially because health insurance plans often do not cover the cost of medical formulas and low-protein foods. I consider our family lucky because our insurance plan helps us pay for Braxton’s medical formula, which currently costs about $1,000 per month. Many parents find themselves changing jobs or even filing for divorce in order to get better health coverage for their children.

In 2021, I began formally advocating for the passage of the Medical Nutrition Equity Act (HR 3783/S 2013), and in the summer of 2022 I was given the great opportunity to speak with Wyoming Congressional representative Liz Cheney, as well as senators John Barrasso and Cynthia Lummis about this important legislation. My goal was to convince at least one of them to become a co-sponsor of the bill, and I was successful! Days after the meeting, I was told that Senator Barrasso would co-sponsor the bill. I celebrated the victory and am now working to continue to influence positive policy changes at the state and local levels and have more rewarding and informative discussions with government leaders planned.

Even with access to the necessary formulas and foods, phenylketonuria is not solved. Our community is still in desperate need for more treatment options. Maintaining a PKU-friendly diet is not a long-term solution, and the challenges it presents makes compliance difficult. But with hope on the horizon — and being a fierce advocate — I see a bright future for my son and the rest of the PKU community.