So You Think You Can Dance to Process Trauma? Here's Why It Helps.

“If you can’t say it, you sing it, and if you can’t sing it, you dance it.” -Anonymous

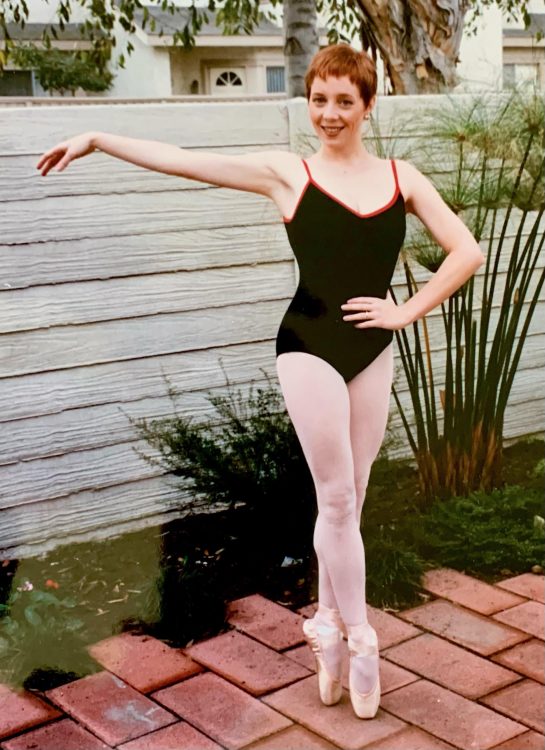

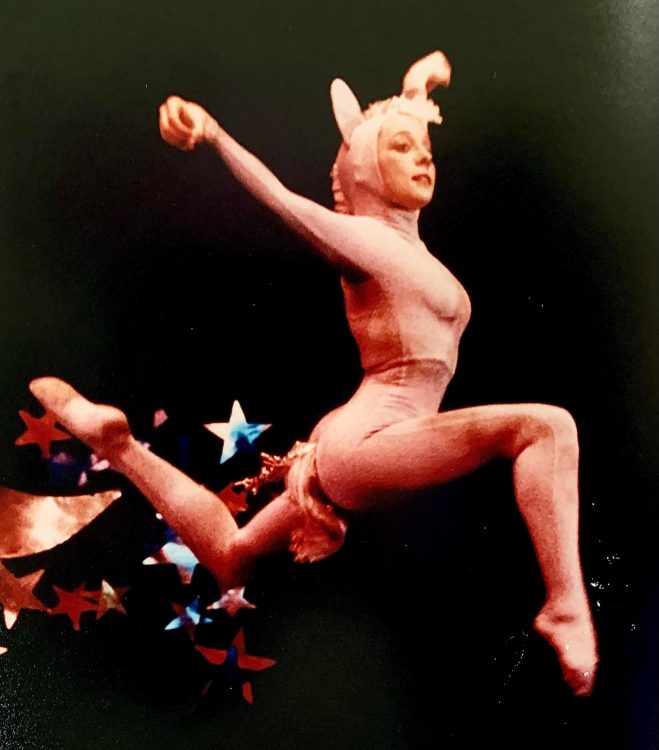

On the season premiere of “So You Think You Can Dance” last week, dancer Maci Montes openly discussed how dance helped her come out of a dark place, and how because of her experience with a suicide attempt, she is now a vocal advocate for mental health. Her words and powerful piece resonated deeply within me. As a ballet dancer turned modern dancer in college, I spent a lot of time trying to reconcile everything I was feeling in relationship to my childhood trauma, eating disorder history, and ongoing issues with depression and anxiety. While I often had no language for how I felt, dance was the one place where I could connect the dots between what was going on in my heart and my head and allow it to flow out of my body.

The connection between mind and body has become widely accepted, and many therapists are incorporating body-focused modalities into their treatment protocols, ranging from somatic experiencing to polyvagal theory to trauma-focused yoga. As Bessel Van Der Kolk, author of “The Body Keeps the Score,” puts it, “I think some of the best therapy one can do is therapy that is very largely non-verbal where the main task of the therapist is to help people to feel what they feel — to notice what they notice, to see how things flow within themselves, and to re-establish their sense of time inside.” It makes sense, therefore that using dance as a tool would be a highly effective form of emotional integration.

According to the American Dance Therapy Association (yes, that’s a thing and I’m feeling like I missed my calling), “Dance/movement therapists focus on helping their clients improve self-esteem and body image, develop effective communication skills and relationships, expand their movement vocabulary, gain insight into patterns of behavior, as well as create new options for coping with problems.”

But how exactly does this work? There are several factors that function together to make dance particularly effective as a therapeutic tool.

1. Bilateral stimulation.

The fundamental tenet of EMDR, bilateral stimulation, enables one to engage both hemispheres of the brain simultaneously, allowing connections to be made that can effectively process memories that may have gotten stuck. While in classic EMDR this bilateral stimulation is achieved through watching someone move their fingers back and forth, many different types of activities can achieve similar results. Body movement where alternating sides of the body are worked in sequence is one of these. Therefore, dance engaging repetition from one side of the body to another can effectuate a similar result.

2. Release of feel-good neurotransmitters and mood regulation.

Exercise and movement in general are known to be great ways of releasing feel-good chemicals like dopamine, which can be a mood elevator. Factor in the element of music in dance and you have a powerful one-two punch of reducing stress hormones like cortisol and engaging parts of the brain associated with emotional regulation. I’d also argue that music has the capacity to transport one to a different time and place. Allowing our bodies to engage in dance in conjunction with this kind of “time travel” can help one solidify a sense of security and reinforce positive feelings associated with that time and place.

3. Vagus nerve stimulation.

The vagus nerve is the longest nerve in the body. It connects the brain to various organs of the body involved in regulating your parasympathetic nervous system. It is well known that trauma can disrupt vagus nerve function, causing dysregulation of everything from digestion to mood. Two of the best ways to stimulate positive vagal functioning are through exercise and deep, slow breathing, both of which are integral aspects to dance. There is also some evidence that stimulating your vocal cords through humming, chanting, and singing can help stimulate the vagus nerve. Since many dance forms involve vocalization, this can be an even more effective way of tapping into the restorative power of the vagus nerve.

While I wasn’t consciously engaged in a disciplined therapeutic dance protocol as a teenager and young adult, I most certainly understood unconsciously and corporally that moving my body to music felt good. My body had brought me so much pain as a child who had been sexually abused and later as a ballerina who had been constantly harassed to try to fit her natural physique into an unnaturally narrow definition of what a dancer should look like, that I struggled to find safety within my own skin. I intuitively discovered that I needed a safe way to reconnect with and inhabit myself from the outside in. Dance, particularly uninhibited and improvisational dance where I allowed my body to flow freely with the music, became therapy for me.

I encourage anyone, with a trauma history or otherwise, to engage in some kind of dance-like movement to music. You don’t have to be a professional or great at it. Nor does it have to involve your entire body. You can sit in a chair or lie on the floor and allow your arms to move and the music to pulse through your body. You just have to allow yourself the space to connect to your body. The key is not to be self-judgmental. This isn’t intended to be performative. Its intent is to be deeply personal and rooted in your sense of who you are both internally and externally.