The Invisible Illness I Never Expected as I Healed From 27 Surgeries

I’ve always thought myself capable of overcoming anything. I was invincible. I was a dangerous woman, out to change the world.

Overcoming illness meant waiting for a fever to go down. Illness was a stuffy nose — a sick day, an excuse to miss a day of school. At 18 years old, “illness” took on an entirely different meaning. Illness meant waking up from a coma, learning that my stomach exploded, I had no digestive system, and I was to be stabilized with IV nutrition until surgeons could figure out how to put me back together again. Illness meant a life forever out of my control and a body I didn’t recognize.

What happened to me physically had no formal diagnosis. I had ostomy bags and gastrointestinal issues, but I didn’t have Crohn’s disease. Doctors were fighting to keep me alive, but I had no terminal illness. There was so much damage done to my esophagus that it had to be surgically diverted. I didn’t fit into any category. Suddenly, I was just “ill.”

I became a surgical guinea pig, subject to medical procedures, tests and interventions, as devoted medical staff put hours into reconstructing and reconstructing me, determined to give me a digestive system and a functional life. I eagerly awaited the day I’d be functional once again — the day I was finally “fixed.” Once I was all physically put together, I’d be eating, drinking, walking, and feeling just like myself again. Right? I desperately dreamed about the day I’d be discharged from the hospital. I’d be happy, healthy and would finally know who I was again. I’d feel real. I’d feel human. From there, I could do anything.

However, after 27 surgeries and six years unable to eat or drink, I learned that the body doesn’t heal instantly. Stitches had to heal one by one. Neuropathic nerves grew back one millimeter a month. Learning to talk again took weeks. Learning to walk again took months. My skin’s yellowish glow from the IV nutrition I was sustained on took years to fade. Not only was there no “quick fix” to healing, there was no “permanent fix,” either. Wounds reopened. I became accustomed to new “openings” in my body leaking at any given moment. I learned that the body is delicate, precious, but incredibly strong.

My body never went back to normal. With no other alternative, I learned how to accommodate it and embrace it for the amazing things its extraordinary resilience. I was shocked and saddened that I could never get my old, unwounded body back.

But what really startled me was realizing what had happened to my mind. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). I had never heard those letters put together before. I knew what “trauma” was, but I didn’t know it could cause so much internal dis-ease and dis-order — illness that I couldn’t see. But that was the biggest shock to me — waking up in a new body and a new mind, troubled by PTSD.

Not only had I woken up in a new body, I now had a mind troubled with anxious thoughts, associations and memories. Overwhelmed with confusion, I used the best resource I could think of — a search engine. I didn’t realize I was suffering from PTSD until the internet defined it for me. Reading about the symptoms of PTSD, I was able to realize there were reasons why I was experiencing so many strange sensations — sensations that made me feel alienated from the rest of the world.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), these are common symptoms that I experienced as a PTSD survivor:

Intrusive Memories. Gaining back my physical health, I was unprepared for flashbacks, images and memories that I thought I had repressed. I’ll never forget the first time I had a French fry. I had been unable to eat or drink for years, and now that I was surgically reconstructed, the world was my endless buffet. I expected relief, fullness and normalcy. Instead, I was jolted back to life with every emotion I had not wanted to feel for all of these years. I learned that the French fry was my “trigger.” Putting food back into my body felt pleasant — it made me feel. Now that I could “feel,” I was feeling everything — including the pain I had tried to swallow for years of medical uncertainty, surgical interventions, and countless disappointments.

Soon, intrusive memories were unavoidable. I would be sitting in a car, buckled into a seatbelt and all of a sudden I would start to panic. I felt locked in, restricted, confined and unsafe. Suddenly, I was remembering what it felt like to be chained to IV poles, unable to move and constricted to a tiny space. My heart started beating rapidly and I started to panic as my memories intruded on what appeared to be a perfectly calm moment. It wasn’t as if I was recalling a painful time. It was as though the doctors were right there with me, peering over my open wound, dictating my uncertain future, and confining me to a world of medical isolation.

Avoidance. When I started to feel these scary memories at any given time, I felt like I had to avoid any stimulant that might make me feel anything at all. Nothing felt “safe.” I lived my life like I was constantly running or fleeing. I spent years locked in my room, journaling for hours with my blinds shut, careful to shut out any outside stimulation that might make me feel. When I was unable to eat, this was a survival mechanism — if I felt, I might actually feel the deadliest sensation of all — hunger. It was too painful to remember every setback and struggle, too overwhelming to recall everything I had lost with every surgery — my innocence, my old body, my sense of self…

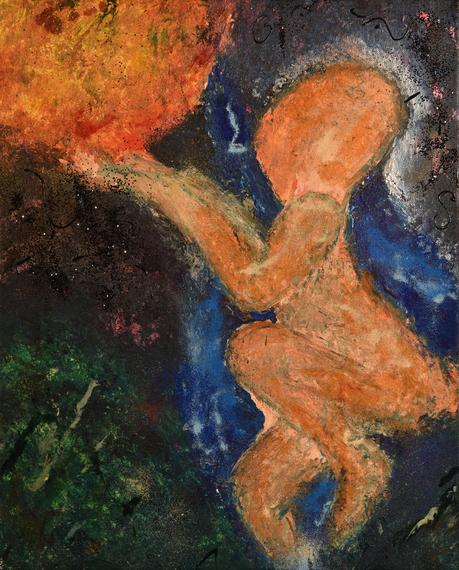

Dissociation. Once I started avoiding my intrusive memories, I got used to the feeling of numbness – so much that I became dissociated. When trauma left me emotionally and physically wounded, I froze to protect myself. I went numb so I didn’t have to feel pain. I went numb so I didn’t have to re-experience what had happened to me and mourn my losses. Becoming numb made my world a blurry haze. The world didn’t feel real anymore (de-realization) as I learned to stay “out of my body.” I would walk around almost like a zombie, compulsively pacing hallways and walking in circles — anything to keep my feet moving rather than my thoughts. Through dissociating, I could avoid really feeling what I need to feel — grief.

Hypervigilance. Staying out of my body and dissociating was how I coped with anxiety. Feeling tormented by my memories, which felt like present realities, I was extremely anxious and irritable. If I couldn’t constantly fidget or find another way to “numb out,” I would start to panic, and would be overwhelmed with even more intrusive memories and raw, forgotten emotions. My anger would end up being misdirected at others, when really I just wanted to shout at my circumstances. My anxiety manifested in all the wrong places — I couldn’t sit still in classes and couldn’t function as a calm, responsible adult. Soon, these symptoms were controlling my life.

This was a list of beliefs I created for myself that helped me stay “numb:”

– If I don’t keep moving, I will feel awful emotions.

– I cannot pause to look at anything. If I do, I’ll remember awful things.

– I must keep doing, and I must always know what I am doing.

– I get a nervous feeling inside if I am in a small space.

– When my body feels pain I am in surgery.

– I cannot stop moving. If I do, I drown.

– If I go outside I will feel too much and it will hurt.

My life changed when my stomach exploded, 10 full years ago. PTSD is something I still struggle with because my traumas happened to me, they have affected me, and they will always be a part of me. But, I’ve learned how to thrive in spite of what has happened to me and for the first time, my life feels bigger than my past. I’ve found healthier ways to deal with memories, flashbacks and emotions.

To live a healthy thriving life, I’ve had to befriend my past, embrace my experience, and express what had happened to me. I needed to tell my story in order to heal. But first, I had to hear my story for myself, rather than avoid it. Once I learned how to hear my own heart-shattering story, and feel the pain, the frustration, the anger, and ultimately, the gratitude, I was able to speak to it. I was able to gently teach myself how to live in the present moment rather than in the world of the trauma. Healing didn’t come all at once. Every day I tried to face a memory a bit more. I called it “dipping my toes” in my trauma. Finally, I could put words to my grief. I was able to write, “I am hurting.”

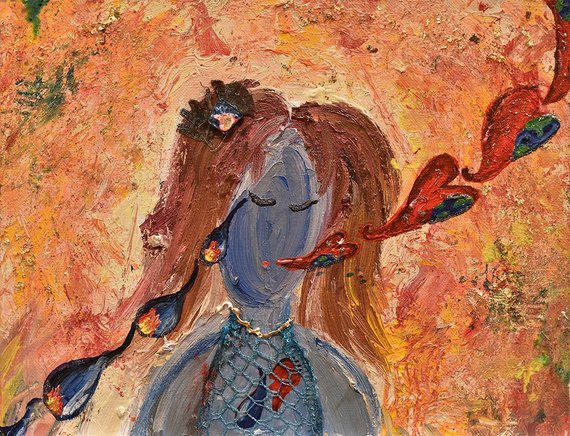

As soon as I was able to write words like “sadness” and “pain,” I allowed myself to explore them. Soon, I couldn’t stop the words that flowed out of me. My memories started to empower me, and I wrote with feverish purpose. I started to journal compulsively for hours as every memory appeared in my mind. Soon, the words couldn’t do justice to my traumatic experience — I needed a bigger container. I turned to art, drawing, scribbling. I filled pages with teardrops, lightening bolts and broken hearts. For me, creativity became a lifeline — a release. It was a way to express things that were too overwhelming for words. Expression was my way of self-soothing.

Once expression helped me face my own story, I was able to share it. And the day I first shared my story with someone else, I realized I wasn’t alone. There were others who had been through trauma and life-shattering events. And there were also people who had been through the twists and turns of everyday life. Being able to share my story emboldened me with a newfound strength and the knowledge that terrible things happen, and if other people can bounce back, then so can I.

I found wonderful resources: the National Alliance of Mental Illness started as a “small group of families” and has blossomed into a supportive, educational organization with local chapters throughout the country; Active Minds educates and empowers college students through nation-wide chapters; and The Jed Foundation offers coping strategies for college students through mental health awareness and suicide prevention programs.

My perspective on illness has changed since my earlier days, and it’s also changed since my last surgical intervention. I’ve learned that illness isn’t always in the physical scars. I’ve learned that some wounds aren’t visible, and some wounds even we don’t know we have, until we choose to take care of them. But I’ve also learned that I’m resilient, strong, broken and put together again, differently, yet even more beautiful — like a mosaic.

PTSD has not broken me. It’s taken me apart, and I’m reassembling myself day by day. In the meantime, I’m learning to love what I can build.

Follow this journey on Amy’s website.