I have incurable cancer. However, I prefer to think of it as a chronic illness, as does my oncologist. I can’t thank her enough for setting my head straight on this right out of the gate. A cancer diagnosis is never pretty, regardless of the stage or type. It’s still cancer, and it’s scary as hell.

My initial diagnosis was stage 4 metastatic prostate cancer. That meant treatment would be systemic, so I wouldn’t have to go through prostate surgery. If there was any good news, that was it. Yeah, chemo was the good news. I can find a silver lining in anything.

Unlike most cancer patients, I never had the “you have cancer” moment. I simply wasn’t feeling well, had some lab work done, and a few days later learned my PSA was incredibly elevated (5,306). At that point, advanced prostate cancer was more or less a given, and a prostate biopsy would soon confirm it. Fourteen out of 14 cores were a Gleason 9 or 10, giving me an overall Gleason score of 9 (5+4). Having an advanced prostate cancer diagnosis meant we’d have to go straight into treatment before I really had a chance to absorb the diagnosis.

My oncologist and I mutually agreed not to talk prognosis. My case was not terminal (as in “you’ve got three months to live”), so we wanted to focus solely on treatment from day one. As I would soon discover, it’s imperative to save all your energy — physical and mental — for the treatment to come. The toxicity of chemotherapy can vary, but experiencing some side effects is pretty much guaranteed. My cancer was advanced and aggressive, so chemo was the best shot at getting it under control.

A driving force behind prognosis is statistics. Survival statistics deal with aggregate numbers and group trends, not individuals. Every person and every cancer is different. I was a living, breathing human being, not a point on a trendline, and I wanted to keep it that way. Nor did I want to go down the path to self-fulfilling prophecy. All I needed to know about five-year survival rates was that there was a curve and then a really long tail. Call me an optimist, but an outlier on the end of that tail was the only place I wanted to be.

A quick warning, because I learned this the hard way: If you ever decide to search the internet for your type and stage of cancer, you will invariably get the spoiler of all spoilers whether you want it or not. It’s out there and almost impossible not to see, so consider yourself warned. However, I found gaining knowledge of my disease very empowering, as it gave me the ability to ask my doctors questions, which in turn gave me some sense of control over my treatment.

Another important thing I learned, and trust me on this: your oncologist will become the single most important person in your life. If your oncologist is not, then you’ve got the wrong oncologist. I can’t stress this enough. Same goes for your entire medical team, and I do hope you’re lucky enough to have one. From the very start, it’s been a group effort involving me, my GP and his nurse, my urologist, my oncologist and her nurse, and an onco-psychologist. You may see these people more than you see your family, but unlike your family, you do have some say in choosing your medical team. Choose wisely, you won’t regret it.

One thing I won’t do is use words like fighter, or warrior, or survivor. It’s perfectly fine if it helps you by identifying with any of those terms. If that’s the case, then I absolutely encourage you to do so. But for me, I prefer simply to say that I’m “living with cancer,” because that’s exactly what I’m doing. I’ll be living with cancer for the rest of my life, and that’s just the reality of the matter. The inescapable fact is that one day, I will die with cancer, or die from it.

One word I won’t hesitate using is “hope.” To quote New York Times bestselling author Karen White from her novel “The Time Between:”

Sometimes hope is all we have, and to lose that is to lose all.

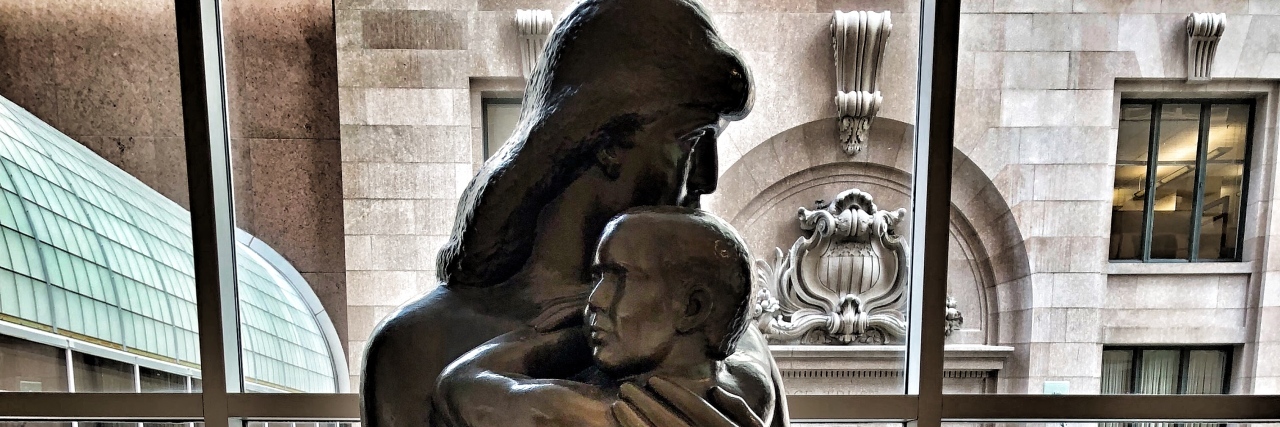

Photo via contributor.