“I remember being so curious about your condition in high school, but too sheepish to ask you. You inspired many investigative diagnostic queries into my mother’s medical texts, and as a result, I learned a whole hell of a lot about many disorders, none of them being the correct one! I wanted to know what you were going through, what it was like to be you. Was it painful? Your ravaged skin seemed like it would be painful even to a tender touch.”

This is an email I recently received from a woman I went to high school with 23 years ago. I had no idea she even knew who I was, as we never spoke to one another. Her words perfectly illustrate why I want to offer advice to parents of children who have visible or invisible issues that make them notably different from their peers.

In 1985, I was diagnosed with scleroderma at age 10. My mother shared minimal information about my disease with me and told me not to tell anyone about it. I love my mom and am eternally grateful to her for raising me. But I do think she made a mistake in her approach to my disease. She had her reasons for her decisions, which she now readily admits were flawed. Like many parents, I think she wanted to deny there was anything wrong with her daughter. If she denied my disease with fierce devotion, maybe it would go away.

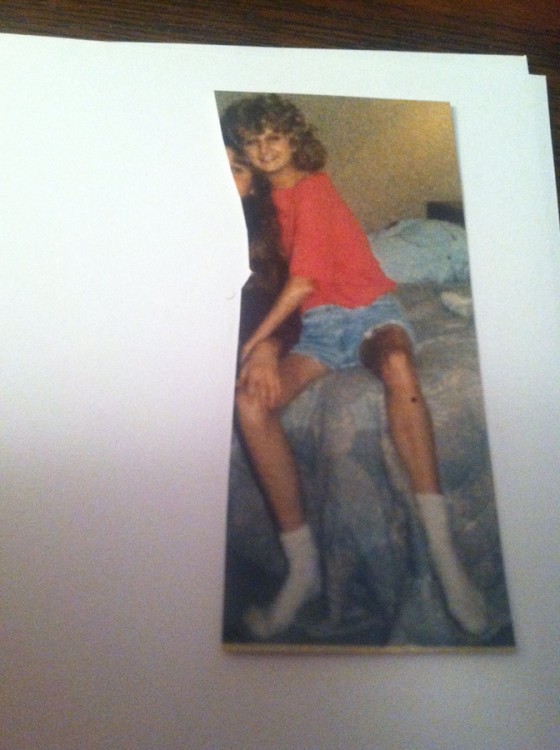

My mom’s plan not to discuss my disease was half-baked at best, as demonstrated by the photos below.

It’s difficult to ignore such a potent physical metamorphosis. My disfigurement aside, there were so many things I couldn’t do that set me apart from my peers. The bottom line is that ignoring something does not make it less real. I was not equipped with the tools to accurately communicate information about my disease. It took me until age 40 to develop a solid and confident response to the whispers that have followed me around for the past three decades.

My advice to parents is to be open about whatever your child’s issues happen to be. Children take cues from their parents. If their parents are hesitant to openly discuss important topics, they will grow fearful of them and the “secret” will fester. Don’t underestimate the toxicity of secrets. Even my best childhood friends knew very little about my disease. Simple questions would trigger fearful tears from me, so they learned quickly not to ask.

Before I became a reading specialist, I was a fourth grade teacher. Each year, I had several students who fell into the “notably different from their peers” category. Some parents forbade the school to talk about their child’s differences with the class. They claimed that they wanted their child to have as normal of an experience as possible. These parents loved their children with fierce intensity and did not want them to be hurt by labeling or negative stereotyping. Of course, I respected their wishes and did not violate their request.

Other parents were open to coming in and sharing information about their child with my class. My students sat on the floor in a circle surrounding the parent speaker and were given the opportunity to ask questions and learn. Sometimes the child wanted to be present for the conversation and even lead the discussion. Other times, the child chose not to remain in the room while the dialogue occurred. Over the years I had parents talk about autism, cerebral palsy, Tourette syndrome, ADHD, peanut allergies, hearing impairments and more. Without exception, these discussions led to deeper understanding and empathy from the students. I only wish I had been brave enough to start off these discussions by first telling my students about my scleroderma and explaining why I looked different. This remains one of my hugest regrets, as I think it would have brought comfort to so many of my former students.

Parenting a child with an invisible or visible condition can present extraordinary challenges. Every circumstance is different and must be carefully considered by those who know and love a child best. Some parents may argue that they don’t want to call further attention to their child or cause them to feel insecure. I’m willing to bet that 99.9 percent of the time, that child already feels quite different. This is strictly based on my own childhood experiences and what I’ve observed in my 19 years of teaching children; I’m no child psychologist.

If I could turn back the clock, I’d want my mom to do this: come into my childhood classrooms each year and talk to my peers about scleroderma. I think it would’ve demystified the rumors that surrounded me and allowed me to be comfortable in my thick skin decades earlier.

My mom is a wonderful lady who has overcome tremendous obstacles in her own life. We’ve all made mistakes, and my purpose in sharing this is not to publicly shame my mother. Instead, I hope to convey the importance of open and honest communication about tough topics and maybe even change some parents’ approach to disclosing information about their kids with visible and invisible conditions.

A longer version of this post originally appeared on Comfortable in My Thick Skin.

Want to help celebrate the human spirit? Like us on Facebook.

And sign up for what we hope will be your favorite thing to read at night.