Navigating your way through the ups and downs of parenthood is tricky at times, and it can be complicated when you have a child with a disability. However, no matter the condition or how much or how little the child is affected, we all want the best for them. They mean the same to us regardless of their needs, and they have the same wants, needs, and emotions.

Many times it is hard for parents of children with disabilities to see things from their children’s point of view. That is where I come in.

I was born with spina bifida myelomeningocele and have a lifetime of experience to share — tips, tricks, and shortcuts I have learned along the way that have made my life easier. I know the emotions of being that little kid wearing the braces, as well as those of the teenager who tries so desperately to find his or her place. That makes me, as well as anyone else who has lived with spina bifida, an expert on how to live with this condition.

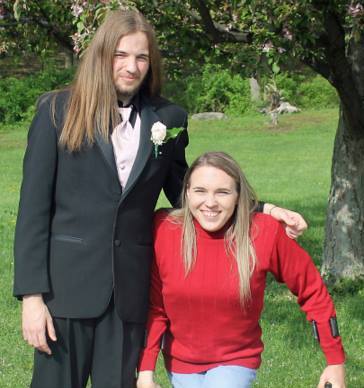

I am also a mother. My husband and I have a 15-year-old son with spina bifida occulta. It is a less severe form of spina bifida, but it presents its own challenges.

When my son was born and I first learned he had spina bifida, I figured, having lived with it myself, I would be prepared for anything. “This shouldn’t be a problem,” I thought. What I didn’t know was that being the patient can be so much different — and easier — than it is to be the parent.

Today, after being on both sides of the fence, I know what I feel as a parent and what I know from growing up don’t always fit together. I have often found myself in a tug of war between my head and my heart.

Since I have started communicating with the parents of children with disabilities, I have always emphasized just how important it is for them to let their kids take chances and maintain a willingness to try new things. I have always felt that isolating a child from all life has to offer does a huge disservice to them. Everyone has the right to live their lives without fear, especially fears imposed by others.

I have spina bifida, so I know what it is to have people tell me I cannot do something. Yes, they had good intentions and no one wanted me to get hurt, but it didn’t feel that way to me. It felt as though someone else was trying to set my limits for me, and I didn’t feel that was fair. I understand not everything is safe. I understand there is a chance I might get hurt. I understand that people worry about me. I also understand that I can’t live my life to make everyone else happy. I understand that taking a risk is a choice; it is a choice I consciously make. I understand that, if I get hurt, it is my fault and no one else. I understand you only live once, so you had better get everything out of it you possibly can.

I also know how it feels to be the person doing the worrying. My son may have a less severe form of spina bifida, but he is still missing one vertebra and has holes in the majority of the others. He has some underdeveloped muscles in his legs and has had to have his neck fused at C1-C2.

I completely understand the need to protect your child from any harm. I understand the worry and anxiety parents feel about not wanting them to have to go through “any more medical crap” than they have already had to go through. I get all that.

This past weekend, I had to practice what I have been preaching. I always have, but this time was the hardest so far.

My husband likes to hunt. He goes on an annual bear hunting trip into the mountains, and this year, he felt our son was old enough to go along. When my husband told me he was taking our son, horrible ideas started going through my mind. Images of all the things that could happen rushed in, and I had this sick feeling in my stomach.

I did not want my son to go. I was worried for him and, as we all know, 15-year-old boys do not always have the best focus. I worried he would wander off or not know what to do if they did see a bear. My husband is more than capable of taking care of both himself and my son in those situations, and I knew he would keep my son safe, so I put that out of my mind.

I also worried about my son physically because of the weakness and bone issues spina bifida presents. As ashamed of myself as I am to admit this, I knew I could scare him. I knew what buttons to push; I knew that keeping him safe at home would help me sleep better. What was worse is I could absolutely justify it to myself, my son, and anyone else by saying, “I just don’t want him to get hurt” or “You know it is going to be too much for him.”

The common word in all that thinking is “I.” It would make me feel better, but at the same time, it would make my son hesitate and limit him — and that is something I can never justify.

I had to have a conversation with myself. I had to remind myself that what I feel is natural, but that I know better. I know life is full of risk. I know my son may get hurt and may not be able to keep up, but he won’t know until he tries. To my husband’s credit, I don’t think he was concerned at all. He knew he might have to go a little slower from time to time or wait on our son, but it didn’t bother him at all.

The weekend approached and I still did not want our son to go, but I had to suck it up and do what I knew was best for him. I also knew I would much rather lose some sleep than make my child doubt himself. He was in good hands, so I kept it all to myself and told him to have a good time and listen to his dad.

I wondered the whole time how he was doing. They were literally climbing up the side of a mountain, moving the entire time from sunup to sundown. I wondered how much pain my son would be in from carrying his gun and whatever else he may have to carry with him. How were his legs going to hold up under that much activity?

But the first night when I spoke with my son, he went on and on about how much fun he was having. At that moment, I knew I was right, and I was really glad I had kept my mouth shut about not wanting him to go. He didn’t complain about anything physical. By the third day, he said it felt like something was ripping the muscles out of his legs and they really hurt. Of course, my first instinct was to tell him to take it easy. I caught myself before I said it. I asked him if it was worth it, and he didn’t hesitate to say, “Yes!” I told him I was glad he was having fun, and we left it at that. I know he was in pain, but that is probably the best workout his muscles have ever gotten. The soreness would go away in a few days, and the workout would do his muscles much more good than it would harm.

My son continued through the five-day trip and was able to keep up. He had a great time with his brother, uncle, and dad. Memories were made that he will carry with him throughout his life. Most importantly, he won’t be afraid to do something like that again. He doesn’t know I ever doubted his ability, so he didn’t know to doubt it himself and proved me wrong. All the limits I set for him in my own mind I chose not to pass along to him.

I firmly believe that, as parents, we hold more power than the disability does in the lives of our children. Most of the time, our children will believe us when we tell them they cannot do something or that they cannot have something they want. Sometimes we will be right; but most of the time, if they are given the freedom, I believe our children will prove us wrong.

As someone who has grown up with a disability, I know what it feels like to have well-meaning people try to hold you back. I know that is completely unfair and can destroy someone’s will to go out into the world and try to make a good life because of the fear it is unattainable.

I know, as a parent, how strong the need to protect is. I have been there in the waiting room during my son’s surgeries. I have been at his bedside and seen how vulnerable he has been. I know the need to do everything possible to keep him from ever having to experience anything like that again.

I am in a unique position: I have been on both sides of the fence. I can tell you that being the patient and being the parent are two completely different experiences. They do not have anything in common, and I have learned that the parents, in my opinion, have the worst end of the deal. Our kids don’t know fear unless we teach it to them. It is only fair to let them explore life on their terms, without hesitation, and without fear. As parents, I don’t think it is possible for us not to feel some fear for them; but no one knows what they can accomplish, so just let them try. You will be surprised.

It is my hope that other parents can take an example from some of the things I have learned so that they can continue to learn and develop a better understanding of their own children with disabilities. I can personally say I understand my parents in a way I never could before.

A version of this story originally appeared on the Huffington Post.