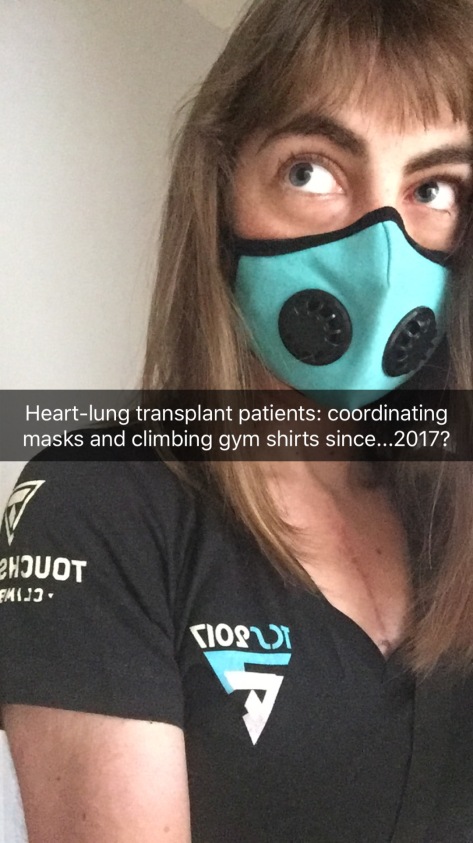

When I started becoming more independent after my transplant, I thought it would be funny to try to go on dates coordinated through Tinder while wearing the filter mask I wear to prevent infection. “You can’t kiss me, and I don’t drink alcohol so I’d rather not meet at a bar, but let’s get some coffee and I’ll only wear a mask for part of the time.” For reasons unrelated to my mask and immunosuppressants, my love life has been fairly bleak lately. I’d like to say I’m single by choice, but I won’t pretend I haven’t gotten hurt. As I am still in a key period of the healing process from surgery, I have focused on avoiding stressful relationships, romantic or otherwise. Following each romantic rejection, I think, “Could be worse – at least it’s not organ rejection!”

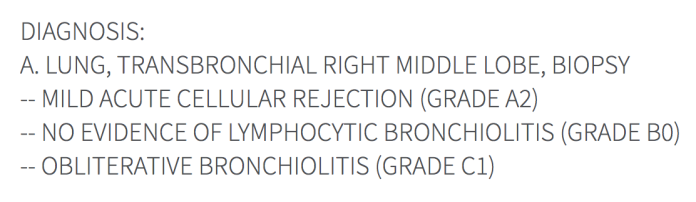

Well, Thursday’s bronchial biopsy came back with a diagnosis of Mild Acute Cellular Rejection (Grade A2). Acute cellular rejection, mediated by T lymphocyte recognition of foreign major histocompatibility complexes, commonly occurs in the first year after a heart-lung transplant. Basically this means my immune system is waking up to the fact that we, uh, switched out my heart and lungs for someone else’s and hoped it wouldn’t notice.  It noticed.

It noticed.

Last May my family and I were told I needed to be listed for a heart-lung transplant. The need for a transplant had been one of our greatest fears for 16 years, but when we finally faced it, we felt a sense of calm. We focused on the actions that needed to be taken, and not on what might go wrong. Well, OK, we are human and definitely wasted our fair share of energy on worrying.

The Pulmonary Fellow I saw on Monday seemed nervous when he told me he wanted to schedule a bronchoscopy because my Pulmonary Function Test (PFT) showed a 7 percent decline in the numbers they use to evaluate my lung function and screen for infection and rejection. He appeared to be asking if I was willing to have the procedure, to which I responded, “Of course!” Bring it on. My team has been conscientious and understanding of how distressing the diagnosis of rejection may be for me. I’m focused on doing whatever needs to be done to get through this. It’s a bump in the road that may slow me down, but challenge breeds creativity, and it was all feeling a little too smooth anyway.

Infection and rejection have been my family’s greatest fears post-transplant. I caught Coronavirus (common cold) at the end of February and treated the infection with rest, fluids, some prophylactic antibiotics and was still able to go hiking! Now we get to see how I conquer the first round of our second fear, rejection. I say first round because, though this is the first time I have been diagnosed with rejection post-transplant, it probably won’t be the last time.

So now I get some huge doses of steroids and we wait and see what happens. I had my first of three outpatient infusions of 500 mg of Solu-Medrol (basically mega-Prednisone) this afternoon and the only change so far is that things are flying out of my hands more frequently – my hands are even shakier today than they were yesterday on 10 mg of Prednisone.

“He who has a why to live, can bear almost any how.” – Friedrich Nietzsche

Last summer, high doses of steroids had me convinced that life was not worth living. But I have lived so fully this past year as a result of the challenges and causes for celebration that my transplant brought. I now have mechanisms in place to remind me that pain is temporary and I can move past suffering. For my infusion today, I proudly wore the T-shirt from yesterday’s Touchstone Climbing Series competition at Mission Cliffs. I speed-walked the 1.6 miles to the gym about an hour after the results of my biopsy came in. My nurse coordinator was probably curious about the noise coming from the DJ and crowds in the background while she told me over the phone to check in at Admitting before going to the Infusion Center, but she didn’t say anything.

I won’t recommend going rock-climbing with a healing sternum, and my last discussion with a doctor ended with him advising I avoid upper-body exercises for the first year after surgery. But indoor rock climbing makes me feel strong and happy. It’s something many of my friends enjoy and I love incorporating socializing with exercise because I’m all about multitasking. The gym is an environment where I can be heard through my mask (loud bars are tough) and instead of giving me dirty looks, other climbers ask me where I got my mask, assuming I am wearing it to avoid the chalk in the air or to train for high-altitude! I take safety seriously: my climbing partners include EMT’s, transplant and ICU nurses. I wear a filter mask the whole time, know my limits and am careful to avoid climbs with portions that would be dangerous to fall from. With my climbing harness double-backed, my belayer’s carabiner locked, Band-Aid’s and Neosporin in my bag, and constant awareness of my own mortality, “climbing on” is a risk worth taking – for me.

Climbing is just one of my “why’s” to live – most of the other “why’s” are proper nouns, not verbs. I’m entering what may be a painful and pessimistic time knowing I will survive it and return to a new normal, living life with the people who make it full.

This post originally appeared on Rose-Colored Mask.

We want to hear your story. Become a Mighty contributor here.