What No One Tells You About Asking for Help When You're Suicidal

“Do you have a plan to hurt yourself?”

“….yes.”

I said yes to the question that tests a person’s true vulnerability. After months of struggling with manic highs and depressive lows, I just couldn’t handle it any longer. I couldn’t take this life any longer. Death scared me, but living terrified me even more.

I had seen all the ads, all the websites, all the statistics: Help was out there. So in one last ditch effort, I summoned all my courage, and during my next psychiatry appointment, I said yes to the question I always lied about. I convinced myself I had nothing to lose, and if it didn’t work, then I could always go back to my plan of suicide. So, I said yes, I have a plan, and yes, I want help. I thought I did everything right. I asked for help just like everyone said I should. No one told me the real truth about asking for help and what asking for help really meant.

After I asked for help, I was sent to a psych ward for a week. They diagnosed me with bipolar I. They gave me medication with promises that these meds would help the highs not be so high and the lows not be so steep. I was exhausted, but proud. I asked for help. I went to the hospital, got a diagnosis and the meds to match. I was set. Finding hope was next in line.

Eight months later, I was once again facing highs that seemed to reach beyond the sky and lows that left me convinced the light at the end of the tunnel was a train barreling at me. What made matters worse was I was not one inch closer to finding hope. No one told me asking for help wasn’t a one-time request. I had done what I was supposed to, and that was supposed to leave me hopeful.

I had already done the deed and asked for help once. There is no way I could summon the courage to do it all over again. Asking for help failed me once. Now, I was going with my back-up plan, suicide.

I planned it all down to the last detail. A week before my set date, I was once again at my psychiatrist office for my monthly visit. I was once again asked the dreaded question, “Do you have a plan?” I hesitated a second too long. My psychiatrist is a smart woman and gently got me to admit my plan.

I was once again back in the hospital. Yet, this time, when it was about time to discharge me, I was asked if I wanted to go to a residential facility for three months. It hit me at this moment that if I was to break the cycle of potentially being in and out of the hospital every few months, then I would have to once again ask for help.

I took a deep breath, summoned every ounce of courage and vulnerability I had and took the plunge. I signed myself up for three months to Hopewell, a residential facility. Those three months turned into six months, which turned into me regaining control of my life in a way I never thought possible.

No one ever explained to me asking for help was going to be one of the greatest challenges of my mental illness. There was no ad, no flyer, and no bullet point under recovery stating that asking for help was going to be a lifelong battle. However, by having that continuous courage and support from everyone who loved me, asking for help has gotten easier. I learned the most valuable lesson: Asking for help doesn’t make you weak. It helps sculpt you into a survivor.

If you or someone you know needs help, visit our suicide prevention resources page.

If you need support right now, call the Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255. You can reach the Crisis Text Line by texting “START” to 741-741.

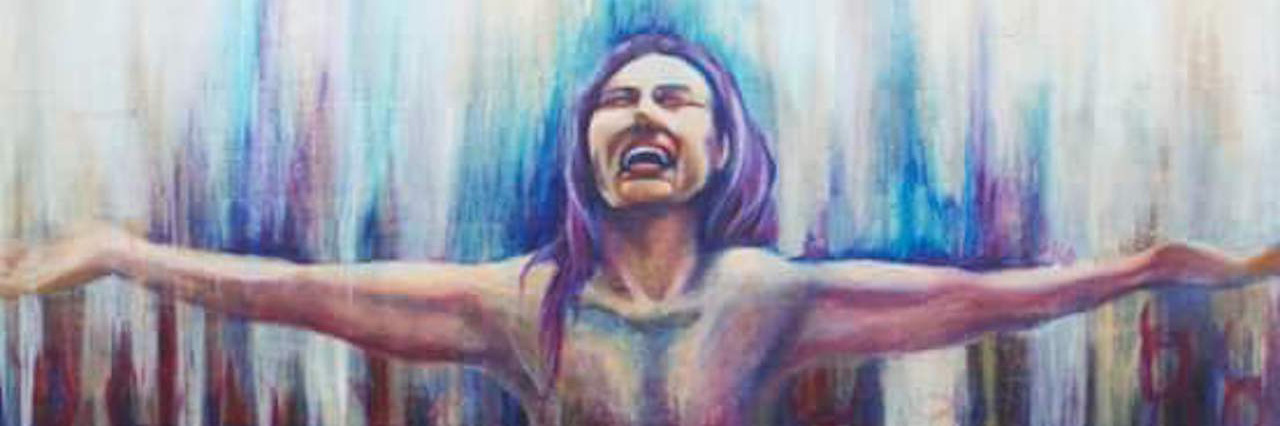

Image: Dana Langenbrunner