Sometime before noon on May 15, 2009, my dad left my parents’ house for the last time. At noon my mother called me in a panic to tell me dad was gone.

I told her to call 911, but I knew then we would never see him alive again. For more than 30 years, my dad had struggled with depression. I grew up prohibited from talking about his suicide attempts, his diagnosis or whether or not he was taking his medication.

Dad’s mental health was a forbidden topic.

My dad left. For two days, we called everywhere we could think of. We finally thought to call the morgue.

My dad’s death by suicide is by far the worst thing I have ever lived through. He didn’t just die. He left us. He walked out the door and never came back. I felt betrayed, abandoned. It felt like a choice. Although, rationally, I understood it was not.

Did he go out the front door or the garage door? He had a picture of our family in his wallet when they found him. Did he look at it and have second thoughts? Was he scared?

I will never know the answer to any of these questions. These are the things I have thought about, for a long time obsessed over, during the last seven years. What if my mom hadn’t gone back to sleep after she got up in the morning? What if she’d been awake and thwarted his plans?

It was tempting to blame her. It was tempting to blame the friend who was visiting the month prior, who took my mom to a museum and gave my dad the opportunity to disappear and attempt suicide for the sixth time.

For years, I blamed myself. I should’ve been more vigilant. It was my responsibility to save him, and I failed. I’ve heard versions of this sentiment from people ranging from his dearest friends to colleagues he hadn’t seen in years. Over and over, people expressed the belief that they could have said or done something that would have saved him. My husband doesn’t think if only he had said or done the right thing it would’ve kept his father from dying of pancreatic cancer. His mother doesn’t think she could’ve prevented it.

I submitted my dad’s obituary to the Washington Post on the chance that they might be interested in publishing it. He’d been in the Peace Corps in Afghanistan. He’d worked with the precursor to USAID in Vietnam during the war. He also had an interesting career in the Foreign Service.

The woman who called said I hadn’t specified the cause of death. I said it was suicide, but my mother didn’t want it published. She said they couldn’t print it without the cause. So I said, thanks, but forget it.

With suicide loss there is shame and there is fear. Would others think my dad was weak? Would they judge him? Would they judge us?

I no longer worry about being judged. I know what my father did not, that mental illness and suicide are not weakness. There is no shame in taking medication or in seeking help. Those are not beliefs I was raised with. I was raised in silence and shame. It took me years of work to arrive at this point. I wonder, if mental illness weren’t stigmatized and if it were discussed in the way we talk about high blood pressure or diabetes, then would my father still be alive? This is another question I cannot answer.

It is common, I think, to define a person who dies by suicide by cause of death. I call myself a survivor of suicide loss. It is my invisible badge I wear every day. It’s become less painful over time, but it is always there.

I’ve survived and I’m stronger, kinder and more understanding for it. I talk about mental illness and suicide all the time. I drop them into cocktail conversation and treat them as casually as one might discuss the weather. I do this for my dad, my children, for friends and for myself.

Sometimes people are shocked, but more often than not, someone confides in me. They take psychiatric medication, see a therapist or have faced the loss of a loved one to suicide. These are all common. What we lack are the avenues for talking about them.

I speak because I want to live in a society where mental illness has no stigma and no attached shame. Where people who need mental health help do not hesitate to reach out and ask for it. Where, if we lose someone to suicide, we do not hide and grieve alone, for fear of being judged.

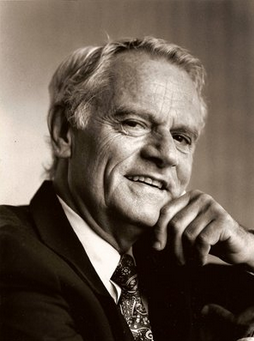

I love my dad, and I still mourn his loss. Now, after seven years, I can conjure up the fun memories and dwell on the good. I can think of him as a whole, wonderful and complicated person. I am able to get past focusing on his depression, on the difficult latter years and on how he died.

He was bright, charismatic and generous. He loved people. He had a Monty Python-esque sense of humor. He embraced the irreverent and thrived on shock value. He was funny, truly funny, and when he laughed, he laughed with his whole body.

While I would undo his death if I could, I am not ashamed to say he died by suicide. Devastated, yes, but not ashamed. I love him, and I am proud of him.

This post originally appeared on This Is My Brave.

If you or someone you know needs help, visit our suicide prevention resources page.

If you need support right now, call the Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or text “START” to 741-741.

We want to hear your story. Become a Mighty contributor here.

Images provided by Lisa Jordan