Parents and Loved Ones: What to Know if Someone You Love Self-Harms

Editor's Note

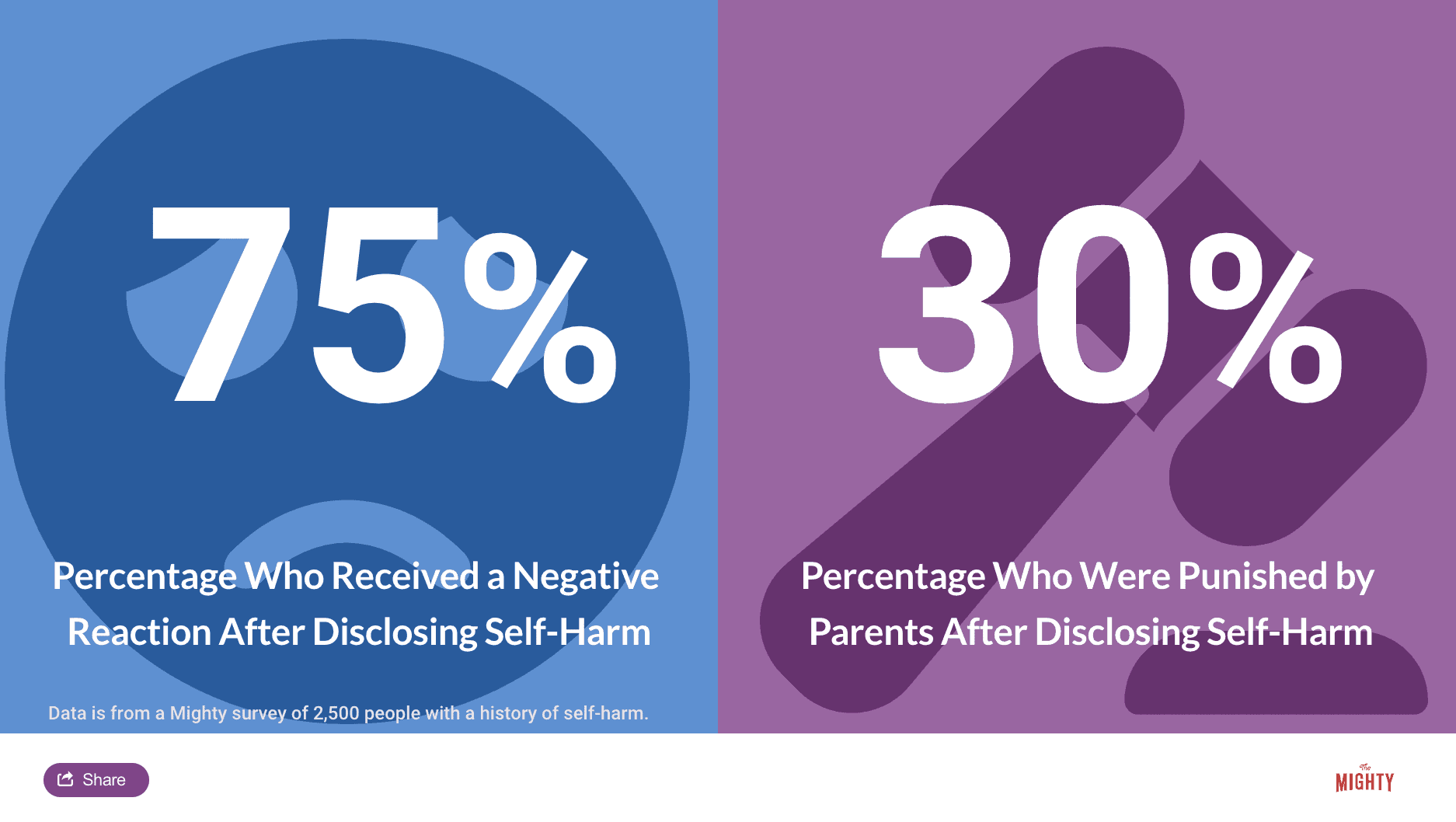

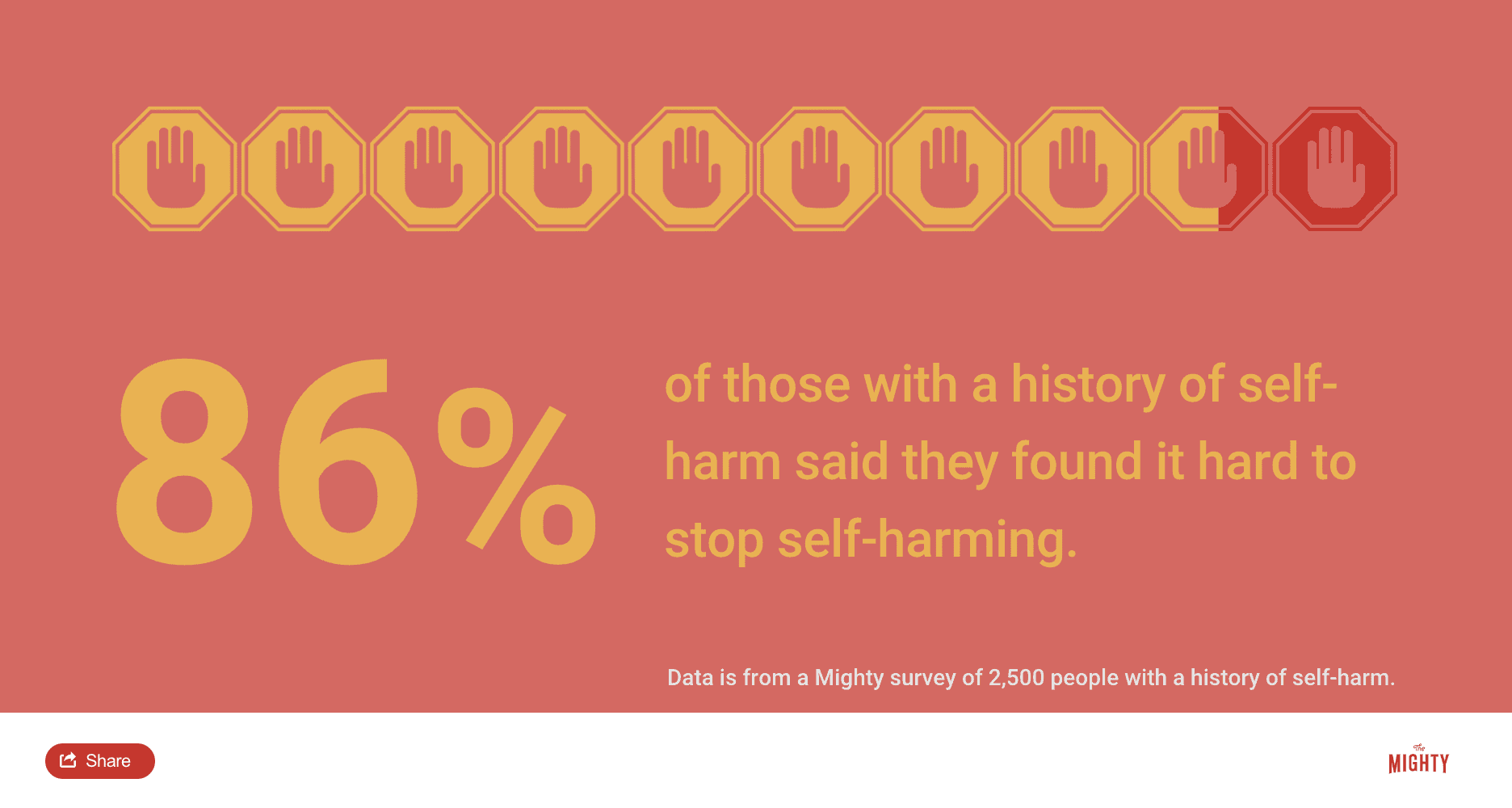

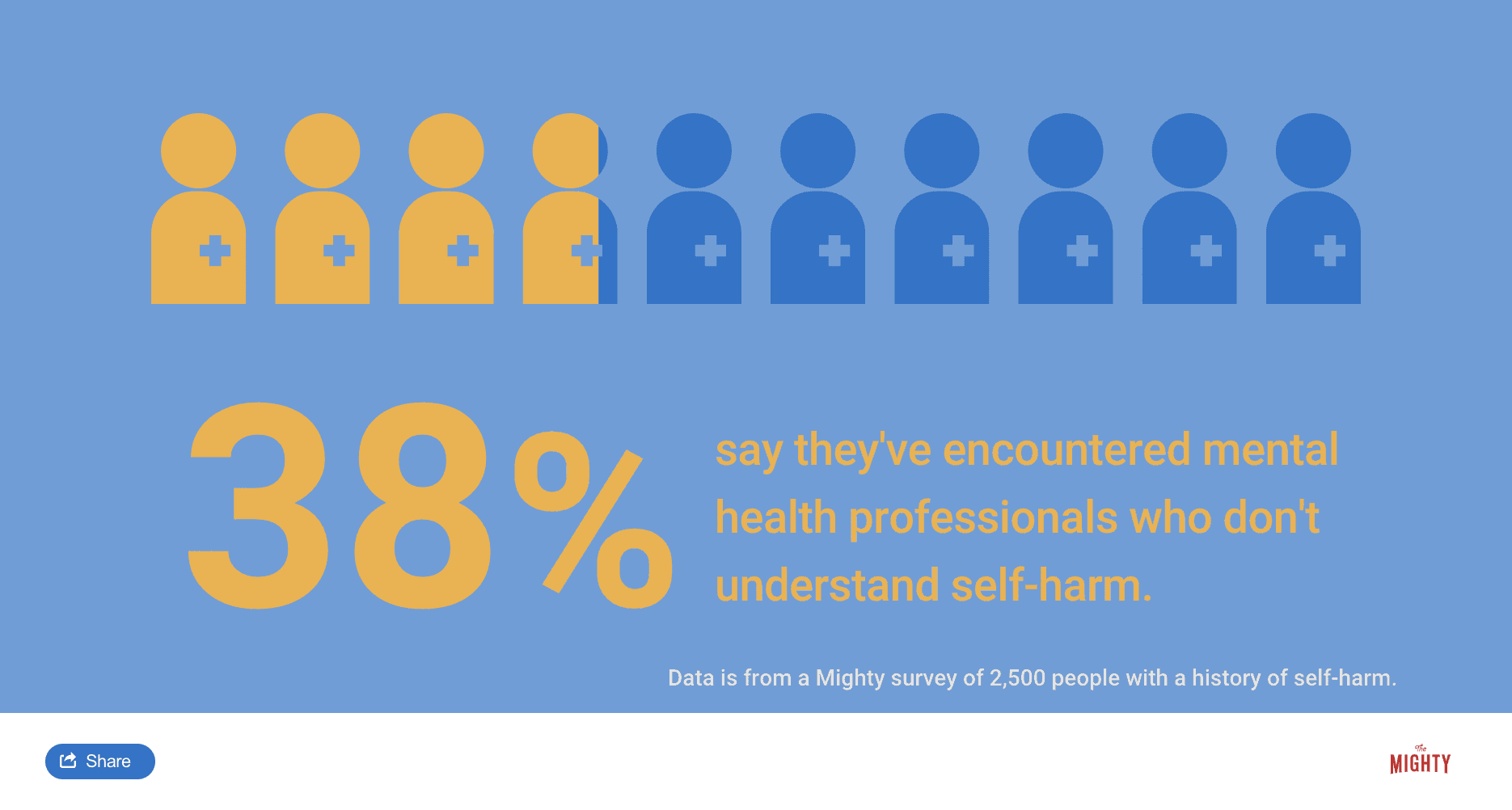

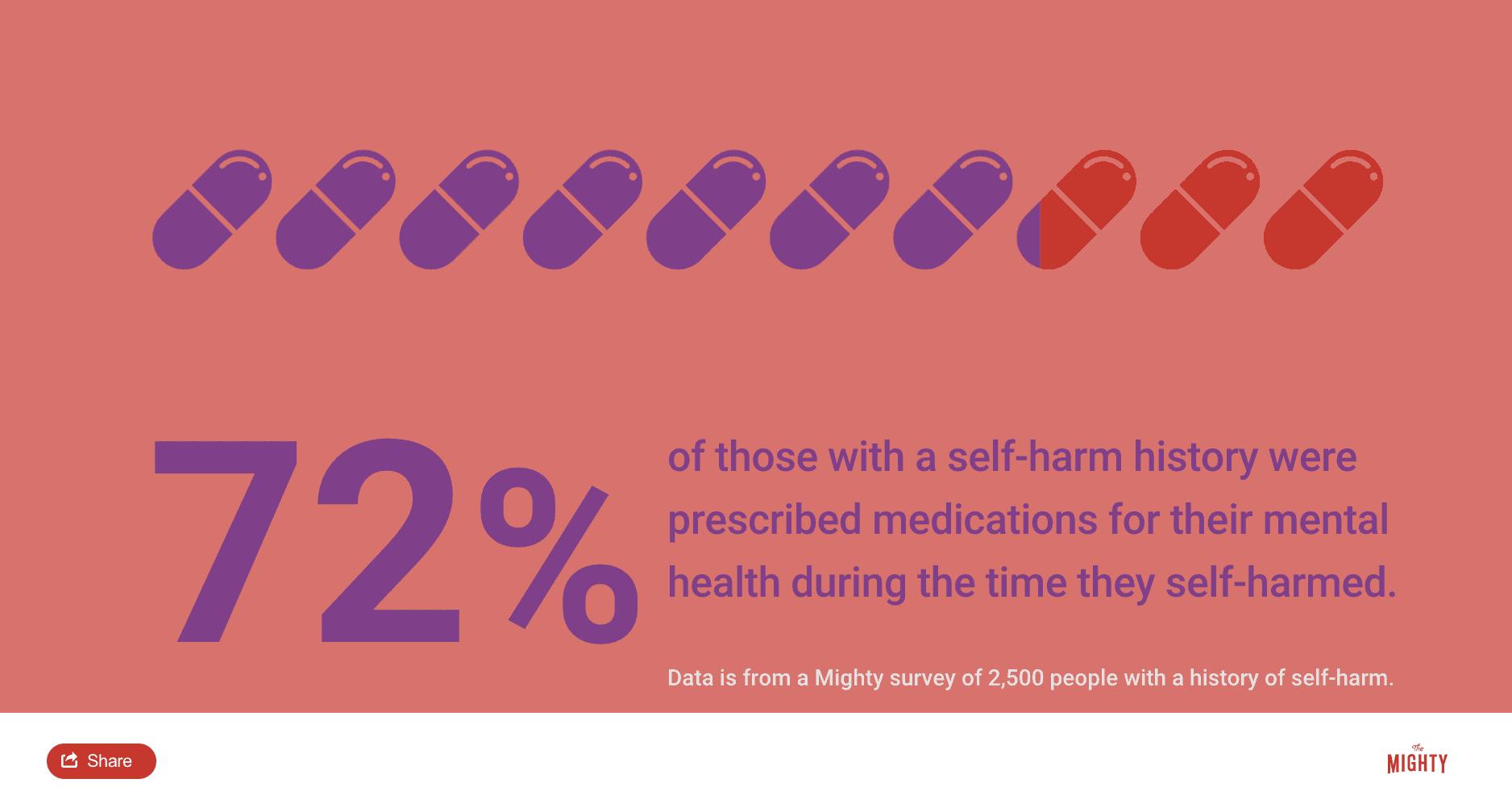

The Mighty’s Condition Guides combine the expertise of both the medical and patient community to help you and your loved ones on your health journeys. For the self-harm recovery guide, we interviewed four mental health experts, read numerous studies and surveyed 2,500 people with a history of self-harm. The guides are living documents and will be updated with new information as it becomes available.

My Child Is Hurting Themselves

It’s difficult to learn someone you love is self-harming. You might feel everything from fear to sadness, anger and helplessness. Know that people self-harm for a reason, usually to manage intense emotions they haven’t learned to manage otherwise. Self-harm needs to be taken seriously, and you can play an important role to help your loved one eventually stop self-harming.

Learn More About Self-Harm Recovery: Overview | For Young People | For Adults | Resources

Medically reviewed by Joanna R. Stern, Psy.D. at the Child Mind Institute

The Facts About Self-Harm | Why Does Self-Harm Make Some People Feel Better? | How to Talk to a Young Person About Self-Harm | How to Get Help for Someone You Love | How to Provide Support At Home | Parent and Caregiver Self-Care | How to Get Help In a Crisis

Parents and Loved Ones: What to Do if Someone You Love Self-Harms

It’s difficult to learn someone you love is self-harming. You might feel everything from fear to sadness, anger, worry and helplessness. Many of these are the same feelings that lead your loved one to self-harm.2 It’s not a manipulative way to get attention or a teenage “fad.” People self-harm for a reason, usually to manage intense emotions they may not know another way to cope with.4 Self-harm needs to be taken seriously, and you can play an important role to help your loved one reduce and eventually stop self-harming.

The Facts About Self-Injury

If you suspect or learn your child or partner is self-harming, it makes sense you would want to talk to them as soon as possible. Before having that conversation, slow down so you can react from a place of support and calm rather than a reactive emotional state that may only intensify the situation. Knowing your facts about self-harm can also make the conversation go a little smoother for both of you.

Self-Harm and Suicide

Your first instinct might lead you to believe self-harm is a suicide attempt. Generally, this isn’t the case — self-harm is an attempt to feel better. It’s a tool to get through a horrible moment when you don’t know what else to do.2 When looked at this way, self-harm comes from an understandable human desire to feel better.9 It’s very different than, “I can’t take this anymore. I don’t want to be alive.”9

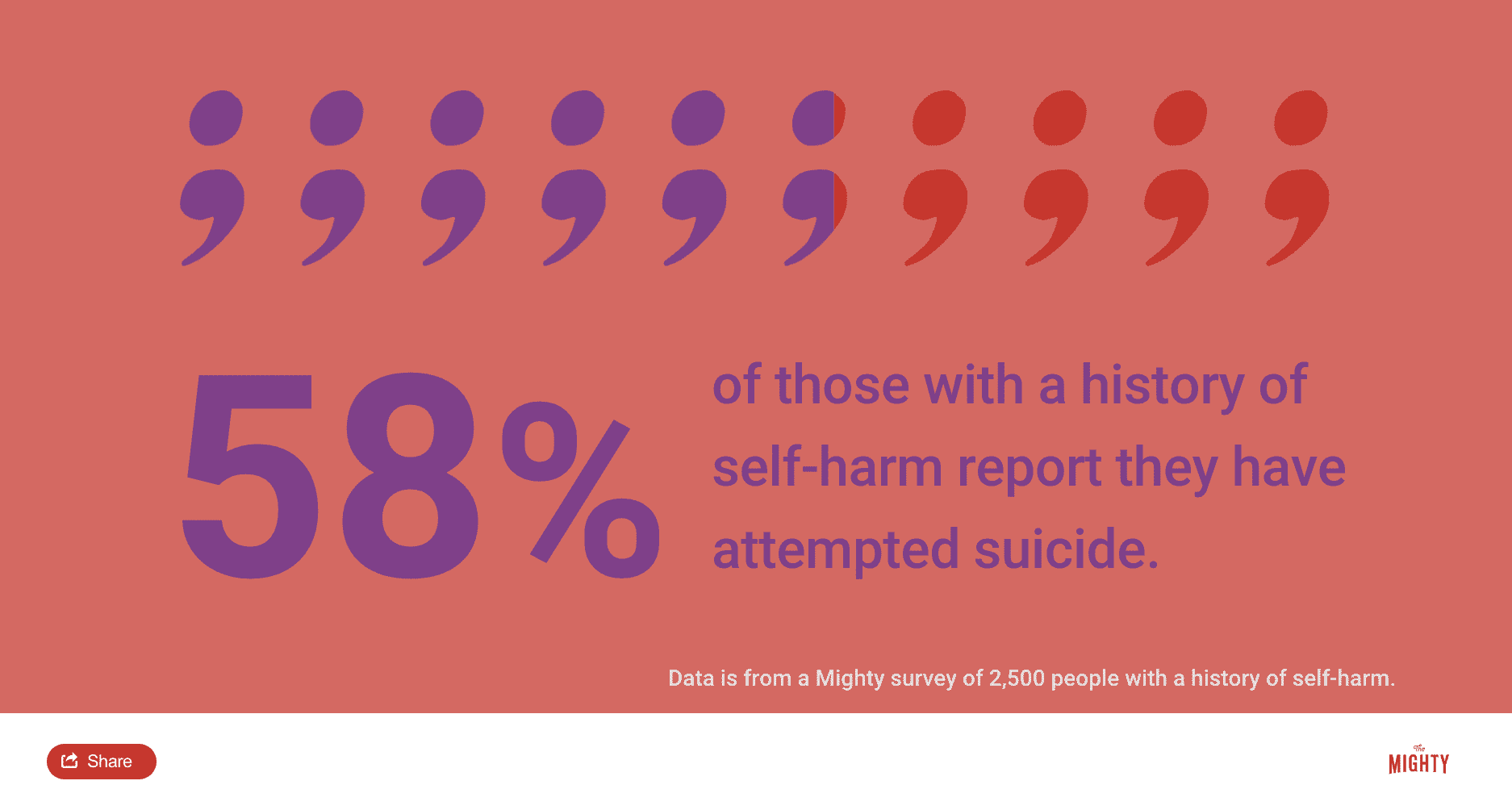

However, you can never assume self-injury isn’t a suicide attempt. You have to ask, especially when you’re first trying to understand what’s happening for your loved one.2 Those who self-harm are more likely to have suicidal thoughts or attempts.2 Research shows that about 35 to 40 percent of those who self-harm have thought about suicide.8 Self-harm should be taken seriously, and you’ll want to watch for any signs your loved one is having thoughts of suicide.

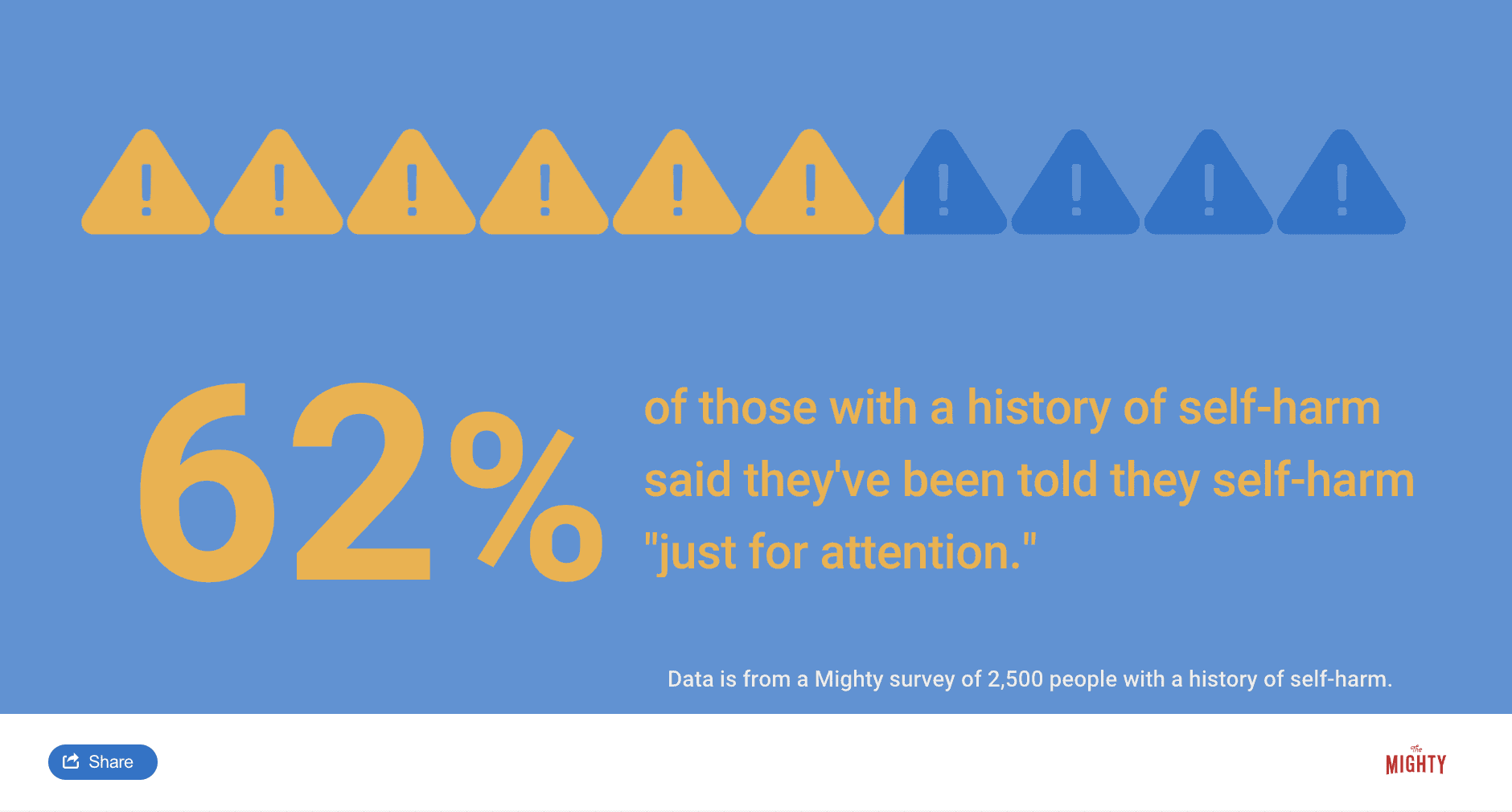

How to Tell If Someone Is Self-Harming for Attention

Saying people self-injure “just” for attention is a myth — it doesn’t hold up nor is it helpful. Self-injury is often a secretive practice, even when it’s used as a way to communicate unmet needs. Research shows that approximately 16 percent of college-aged students who self-harm won’t even tell their therapist.3 For this reason, it’s better to conceptualize self-harm as a “support-seeking” behavior. It’s important to honor that self-harm can communicate a need for support and to work with your loved one to find other ways to express their needs.

When It Feels “Manipulative”

For parents especially, your child’s self-harm may feel manipulative or it can feel like you’re being baited.9 If you find yourself saying, “This feels like a manipulative act,” try asking yourself, “What’s really going on underneath?”.9 In many cases there’s a desire for connection but young people especially may not know how to respond or ask for the connection they need. They might play cat and mouse and can be confused, but if you realize your child is looking for support and just doesn’t know how to ask for it or how to receive it with grace, it might help diffuse some of the irritation you can feel.9

Take Self-Harm Seriously

Perhaps you only see a few minor scratches or know your child’s best friend self-harms so you think they’re probably just copying the behavior and it will go away on its own. Regardless of what it looks like, take self-harm seriously. Even a few scratches or what looks like copycat behavior is an expression that your child or friend is struggling. By addressing self-harm early, it can prevent escalation and you have the opportunity to assist your loved one get their needs met in a healthier way.

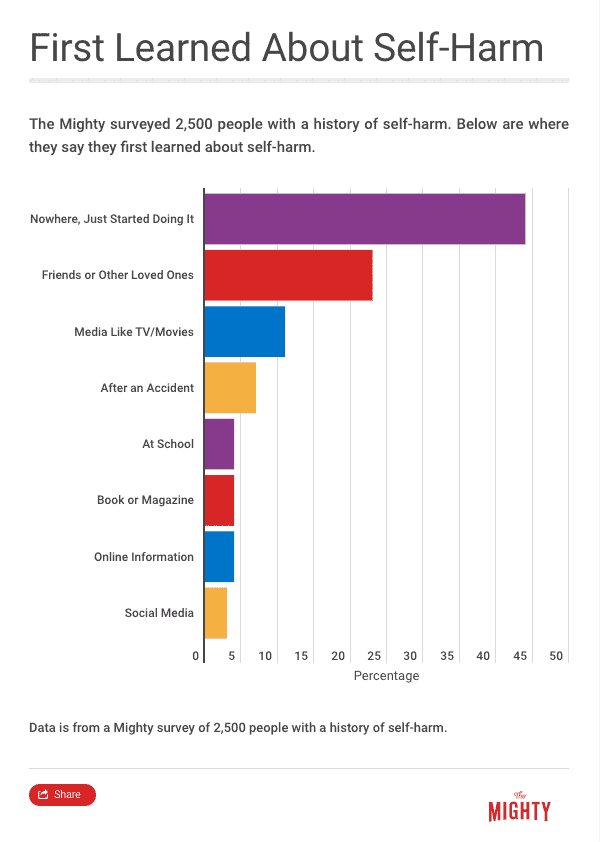

Is Self-Harm Contagious?

Self-harm both is and isn’t contagious. For those with other effective emotional coping skills, even if they decide to try self-harm to see why people do it, they won’t get the benefit and probably won’t try it again.2 Self-harm serves a purpose but not for everyone. For that reason, it’s not contagious on its own, though it can be for those who are vulnerable and learn self-harm could be a solution to their problems.

For those who self-harm to regulate their emotions, seeing graphic images of self-harm or hearing about how other people self-harm can be contagious or trigger an episode of self-injury. When visiting online sites or working in a therapy or support group, it’s important to keep graphic depictions or detailed information about self-harm behaviors to a minimum to avoid contagion.

Warning Signs of Self-Harm

Oftentimes you might suspect something is going on with your loved one, but you don’t know exactly what. Many parents find this is their experience with self-harm. On the outside everything might seem fine — your child still gets good grades, plays on the school soccer team and spends time with friends. Yet something is off. While many who self-injure keep it hidden, you may be able to pick up on some subtle warning signs.10

Here are some signs to watch out for:10

- New wounds that occur frequently or near the same area

- Unexplained scars or other marks

- Use of bandages or band-aids, especially if they’re worn for long periods of time in the same area

- Dressing in long shirts or pants even when it’s warm or hot

- A new affinity for accessories like cuffs or wristbands that hide parts of the body

- Disinterest in activities that would expose the body like swimming

- Collections of self-harm tools (i.e., sharp objects) or wound-care supplies

- Seeming preoccupied or emotionally and physically distant

- Social withdrawal

- Increase in compulsive behaviors, acting out or anger

- Hinting at feelings of shame, worthlessness or self-hate

Why Does Self-Harm Make Some People Feel Better?

A lot of people don’t understand or see the connection between the physical pain of self-injury and how it could make people feel better at all. You might just see “ouch.” Though researchers aren’t 100 percent sure why self-harm works in the brain and body, they do have some pretty good ideas. It’s all about how the brain understands and processes both emotional and physical pain, sometimes at the same time.

Pain Offset

One strong hypothesis about why self-injury regulates emotional pain is called pain offset.15 For a long time, it was believed that all people who self-injure either had a high pain tolerance or just didn’t feel any pain at all. There are times when your loved one might not feel pain during self-injury because they dissociate or disconnect from their body. However, the majority of the time, people do feel pain when they self-injure. It might even be important to feel the physical pain, and that’s where pain offset comes in.7

It starts with pain onset, which is the pain that happens when someone self-injures. Then, once the method of self-injury is removed or reduced from the body, they experience pain offset. People feel a reduction of that initial physical pain in addition to feeling better than before they started self-injuring. Researchers call this pain offset relief. The reason it works this way is because the brain probably processes emotional and physical pain in very similar ways — there’s an overlap between emotional and physical pain.

To get technical, a neural overlap in the anterior cingulate cortex and anterior insula parts of the brain tricks it into thinking a reduction of physical pain is the same as a reduction in emotional pain. As physical and emotional pain overlap in the brain, it can’t really tell if the change is less physical pain or less emotional pain. So when someone experiences less pain in one area, like physical pain offset relief, they also feel emotional relief.7

You may have noticed by now that self-harm doesn’t work for everyone — some people just feel physical pain and it does nothing for their emotions.10 If your loved one self-harms, they’re probably wired to be more perceptive of emotion and pick up emotion very acutely within their environment and within themselves.15 When people don’t initially learn skills for how to deal with intense emotions, self-harm might be very effective.15

Endogenous Opioid System and Endorphins

Beyond the pain offset principle, there are other theories as to why self-harm might make people feel better, particularly the endogenous opioid system.15 The endogenous opioid system regulates pain, reward, stress responses and other parts of the autonomic nervous system, the system in charge of automatic bodily functions like your heartbeat.2 The endogenous opioid system goes about its business using three peptides — β-endorphin, enkephalins and dynorphins — and three receptors — mu, delta and kappa.2

Experts believe self-injury engages the endogenous opioid system (think of it as an “internal pharmacy”). The endogenous opioid system releases “feel good” chemicals like endorphins, which can regulate emotions down from a state of high agitation to a calmer state. Or it moves someone from a state of dissociation to a state of feeling present (or at least more present than they were) pretty quickly.15 Endorphins, a hormone released by your brain and nervous system when you feel pain or stress, produces an analgesic effect or relief from pain, which is likely key in this process.10, 15

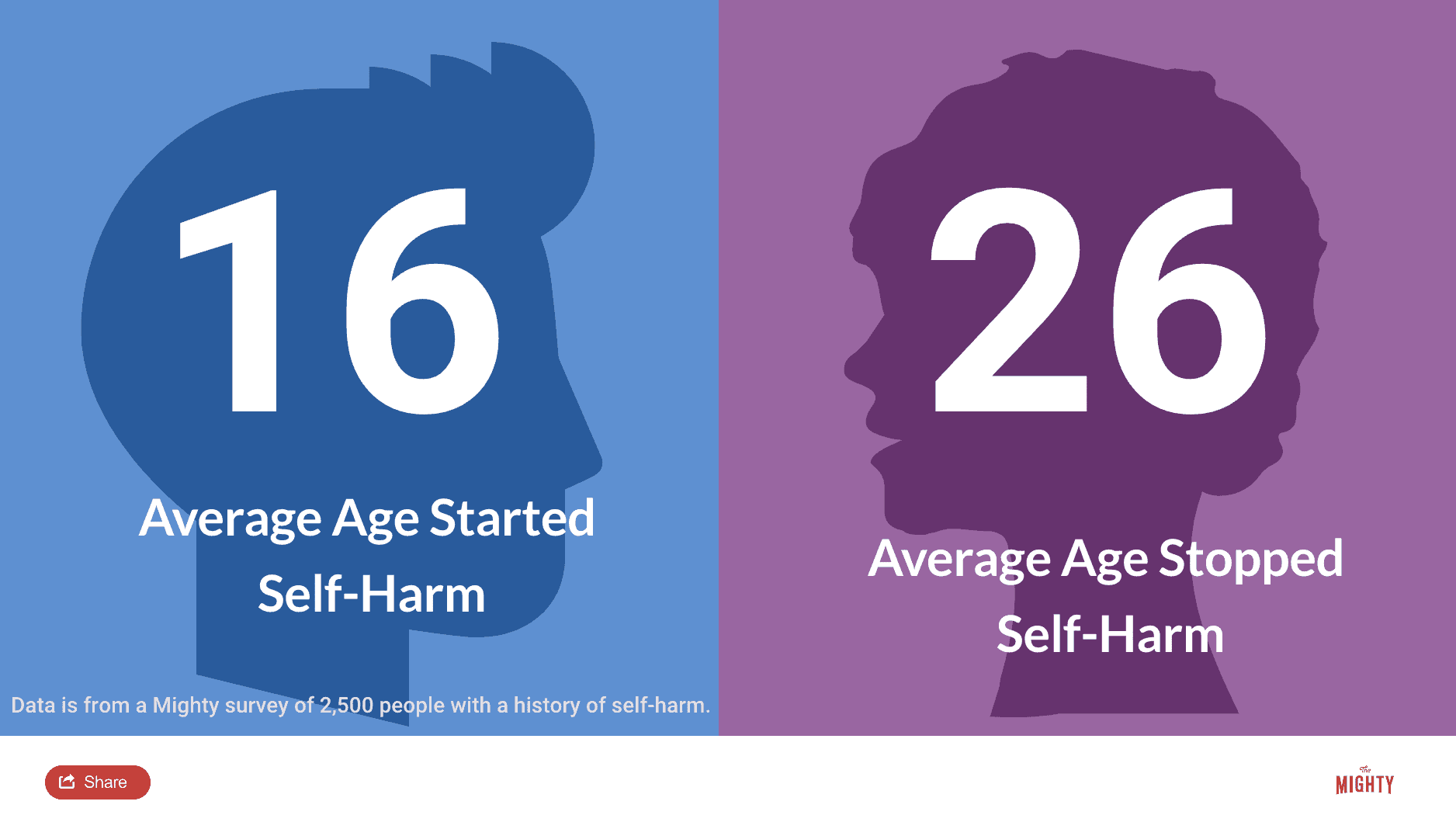

Self-Harm and the Developing Brain

Statistics show that the majority of people who self-harm are young people under the age of 24 and many will stop self-injuring about five years after they start.3 Part of the reason they’re more likely to start self-harming in this age group has to do with brain development. Through adolescence and emerging adulthood, the parts of your brain that help you self-regulate are still developing.11 As you age, these areas of your brain come online more predictably and it gets easier to self-regulate emotions without self-harm, as long as you grow up in a safe environment and learn effective coping skills.

Why It’s Important to Understand Why Self-Harm “Works”

A lot of research on self-harm started by trying to understand the psychology of why your loved one might self-harm. More recently, however, experts have started looking into why self-harm works in the brain and body. Though theories like pain offset and how self-harm might activate the endogenous opioid system don’t necessarily inform what treatment and coping skills might help with reducing and stopping self-harm, they can help take some of the stigma away from self-harm.11 It can help you and others understand there’s a physiological reason why self-harm works for some people.

How to Talk to a Young Person About Self-Harm

Before you approach your loved one to talk about self-injury, take a moment to get centered and calm. It’s normal to experience a range of reactions and you might even blame yourself for your loved one’s self-harm, especially if you are a parent. People who self-injure generally do so because they’re hurting and aren’t sure how to manage their emotions otherwise. Going into the conversation from a reactive place isn’t going to do either of you any favors and may even make the situation worse.

Try to plan your approach. You don’t want to interrogate or blame the person who self-harms. It might feel more comfortable and like you’re more in control of the situation if you jump right into problem-solving mode. However, know that decreasing self-harm isn’t a quick fix — it’s a process. You need to get comfortable with being uncomfortable for a while as you support your loved one through learning new ways to cope, starting with your initial conversation about self-harm.

Strategies for Talking About Self-harm

One of the best ways to approach a conversation about self-injury is to ask respectfully curious questions.11 These kinds of questions communicate a genuine wish to understand the other’s experience. To start, ask permission to ask a few questions. Preface this with a statement such as, “I care about you and I want to understand more about your experience.” Keep in mind that even a child is the expert in their own experience.4

Express your care and concern while still asking the important questions.11 This might include, “Why does self-injury work for you?” “What are some reasons you might want to stop self-harming?” “What might be helpful for you as you try to stop?” Listen actively during the conversation and avoid responding from a reactive place.12 Validate the feelings your loved one expresses and let them know there’s nothing “wrong” with them.4 If you’re feeling angry or overwhelmed, it’s OK to ask for a little breather before coming back to the conversation.

If feelings come up for you that you can share using “I” statements, that’s a great model of how to express emotions without acting out.11 For example, you might say something like, “I feel sad and worried that you are hurting yourself.” By staying calm and honest, you’re able to model effective communication. You’ll also open a door to further conversation and support down the road.

What to Avoid When Discussing Self-Harm

In an effort to do something and take away your child’s or your partner’s pain, you may want to take a fix-it approach.4 No matter how well-meaning, this will likely only put your loved one on the defensive. That jumping in can come across as, “You’re not listening to me,” instead of, “Sounds like you’re going through a really hard time and I can understand why you’re doing this because of the difficult emotions.”4

You’ll also want to avoid demanding your loved one stops self-injuring immediately or asking them to sign a no-harm contract.2 It’s not that simple and this approach prevents those who self-harm from expressing their needs. It may also make them more secretive about self-injury. As uncomfortable as it is, behavior change is a process, and the best thing you can do for someone who self-harms is validate their feelings and approach any discussion from a place of respect, validation and empathy.

Asking the Right Questions

Young people especially sometimes use “concrete thinking,” where they answer very literally the question you ask.2 So for example, you may ask, “When’s the last time you cut yourself?” They might say two weeks ago, but you discover they self-harmed using a different method last night. They’re not lying to you on purpose — they just have a concrete thought process. Don’t be afraid to ask the direct questions: “When was the last time you hurt yourself on purpose?” “Were you having any thoughts of wanting to die when you hurt yourself?”2

Body Checks

It might be tempting, especially if you’re a parent, to demand to check your child’s body for new signs of self-harm. Don’t do this. It is intrusive, can be perceived as blaming or shameful, and will most likely only make your child more secretive and shut down your relationship.2 Even asking to see someone’s self-harm wounds isn’t recommended because it may trigger additional self-harm.9 However, you also need to balance this respect for privacy with the potential need to assess the wounds if you’re worried the self-harm might be severe enough to require medical attention.

Take Responsibility

For parents especially, it won’t always be easy to remain calm when talking about self-harm. But you are the adult, which means your emotions and reactions are your own responsibility. Be mindful not to accidentally place that responsibility on a child. It’s not a child’s job to reassure you or make you feel better. If you’re struggling, which is normal, reach out to another adult to discuss what you’re going through before approaching your child.

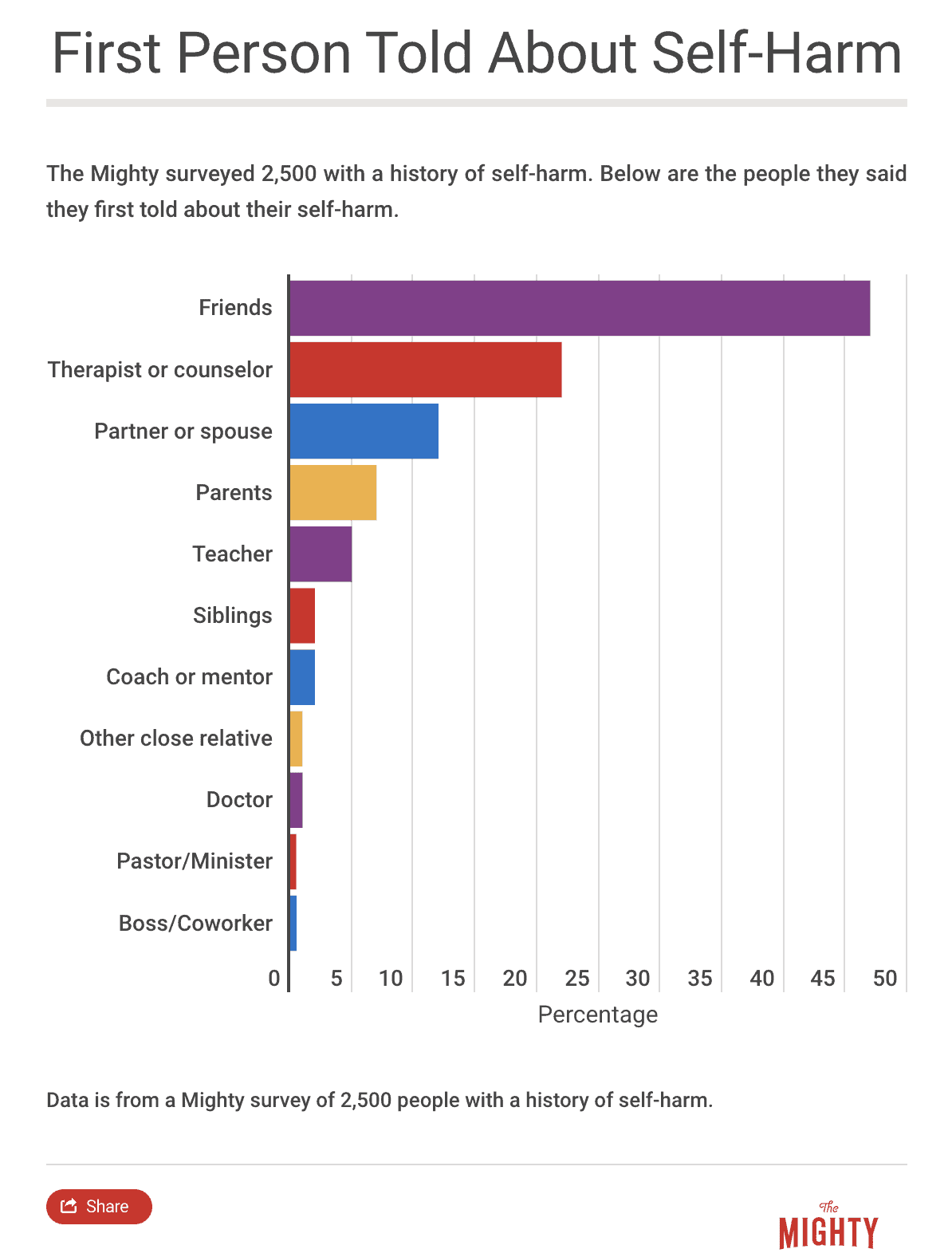

When a child approaches you about their self-harm, that’s a big step on their part. You may actually find you feel relief knowing what’s really happening for your child. A self-harm disclosure can also have a positive impact on the relationship if you’re able to show up as a calm and supportive pillar.

How to Get Help for Someone You Love

Learning new skills to stop self-harming is possible. It’s also a process, and everybody’s journey will look different.4 Those who self-harm also need to learn to tolerate difficult emotions, gain skills and tools to manage their emotions in a more effective and safer way and address any unresolved issues that may trigger their self-harm. None of this will happen overnight, and your loved one is going to need you throughout the process.

Behavior change isn’t linear. Someone may have another episode of self-harm after six months without self-injury. This doesn’t mean all their hard work has failed — your loved one isn’t back at square one.4 After a self-harm episode that occurs after a period of an absence of self-harm, encourage your loved one to reflect on the skills that got them through six months and what triggered the most recent episode. Celebrate the hard work it took your loved one to get to that point and encourage them to keep moving forward armed with new information.

How to Find a Therapist

A therapist is a neutral party who your loved one might have an easier time opening up to about self-harm. Trained mental health professionals are also equipped to teach your loved one alternative coping skills while addressing underlying mental health issues or other self-harm triggers. Make sure a potential therapist is up-to-date on the latest research and won’t fall into old myths that can be harmful.7 Arrange for your child or loved one to talk with the therapist initially to determine if they feel comfortable.

If you want to pay for a child or partner’s treatment through your health insurance, you can look up providers through your insurance company’s directory. The National Alliance on Mental Illness offers a helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264) to assist your search for mental health treatment options in your area. Other websites such as the ones listed below also offer a search function to find local therapists:

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy

One type of therapy that’s known to be highly effective in helping you reduce self-harm is dialectical behavior therapy (DBT).7 One study, for example, found that for every two months of participation in DBT, people were able to reduce their self-harm by 9 percent.9 DBT was originally developed in the 1980s with those who lived with self-harm, suicidal ideation and borderline personality disorder (BPD) in mind. However, DBT has since been shown to be effective for many other mental health conditions, including depression, anxiety, eating disorders and substance use.

DBT teaches skills that are organized into the following four modules:2

- Mindfulness

- Distress tolerance

- Emotional regulation

- Interpersonal effectiveness

If you work with a DBT therapist, they might also work with you and your family on a fifth set of skills called Walking the Middle Path to help you communicate better with your parents so you both understand what’s going on.2 All the DBT skills are designed to help you tolerate big feelings effectively without self-harming, learn how to make decisions that help you balance emotional and rational thinking and help you more effectively interact with others.

You learn valuable skills like:

- Mindfulness, which helps you be in the present moment and focus on one thing at a time

- Radical acceptance, which helps you to tolerate the distress of unpleasant circumstances that you can’t change right away

- How to “ride the wave” of a strong emotion without acting on it

- How to ask for what you want or say no effectively

For young people and families participating in DBT skills groups, you will also learn skills like dialectical thinking, or how to understand and appreciate both perspectives in a given situation. DBT teaches you to approach your thoughts and emotions from a non-judgmental stance, which can be extremely important in learning to reduce self-harm and understanding the non-linear nature of progress.2

A full DBT program includes weekly sessions with an individual therapist, access to a therapist to provide real-time coaching in skills use outside of sessions (usually offered 24/7) and a weekly skills training group with other people experiencing similar things. Some therapists will offer treatment that incorporates aspects of the DBT skills described or even a skills training group you can join without participating in a full DBT program (particularly if you already work with another therapist you feel comfortable with).

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Another therapy that is sometimes used to decrease self-harm is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) because it focuses on changing thoughts, emotions and behaviors. CBT therapists will help your loved one examine what happens for them in the moment when they feel the need to self-harm and brainstorm strategies to cope with self-harm urges in a more effective way.

Other Types of Therapy

There are hundreds of types of therapy, from talk therapy to DBT and CBT. While DBT and CBT are two of the most recommended types of therapy for reducing self-injury, sometimes it’s hard to find a therapist who uses these skills near you. When you’re looking for a therapist, ask what types of therapy they are trained in, because often therapists know several different kinds of skills or ways of working with people, including DBT or CBT skills. If you can’t find a therapist who knows DBT or CBT skills in your area, look for someone who has experience treating self-harm and who makes you feel comfortable enough to open up.

Medication

Your loved one’s therapist might recommend a consultation with a psychiatrist, a medical doctor who specializes in mental health. Especially if your child, partner or friend has an underlying mental health condition, medications can help with reducing the underlying problems in brain chemistry that lead to self-harm. For some people, medications level out their moods — like the lows of depression or extreme highs of mania. This can help stabilize your loved one so they have more energy and mental space to gain ground in their progress toward learning new coping skills.

What to Expect From a Therapist

When your child or even partner is in therapy, you might wonder how much you will know about what goes on in therapy. Will the therapist tell you what your child says during their appointments? Do you have the right to know everything, especially when you’re paying for treatment? What is and isn’t appropriate to ask of a therapist? How will you know how to support your child at home or know if they’re in danger?

Therapists are required by law to disclose if a client is in danger of killing themselves, self-injuring so severely the injuries may be life-threatening or hurting someone else. You can rest assured that your child’s therapist will alert you if there is a serious issue that needs additional attention. However, self-injury might be a little different, and your child’s therapist may opt to maintain your child’s confidentiality, which is generally beneficial.

After a therapist determines your child isn’t making a suicide attempt, each therapist will have a slightly different approach for how they handle self-harm disclosures from young clients. You can ask your child’s therapist their philosophy up front. Know that many therapists with a lot of experience working with people who self-harm will not disclose your child’s self-injury to you, or anything your child says in sessions. If a child knows you are told everything they say in therapy, they won’t feel safe opening up, which can limit their progress. 2

However, therapists also know that parents are an important part of supporting their child’s recovery process. Therefore, a therapist will likely encourage your child to tell you directly about the self-harm when they are ready.2 This approach is more empowering for your child and it ensures they feel safe and supported in both therapy and at home. Know that when a therapist won’t tell you what’s going on in therapy, it’s for your child’s benefit. You can also be confident that if your child’s life is in danger, you will be informed right away.

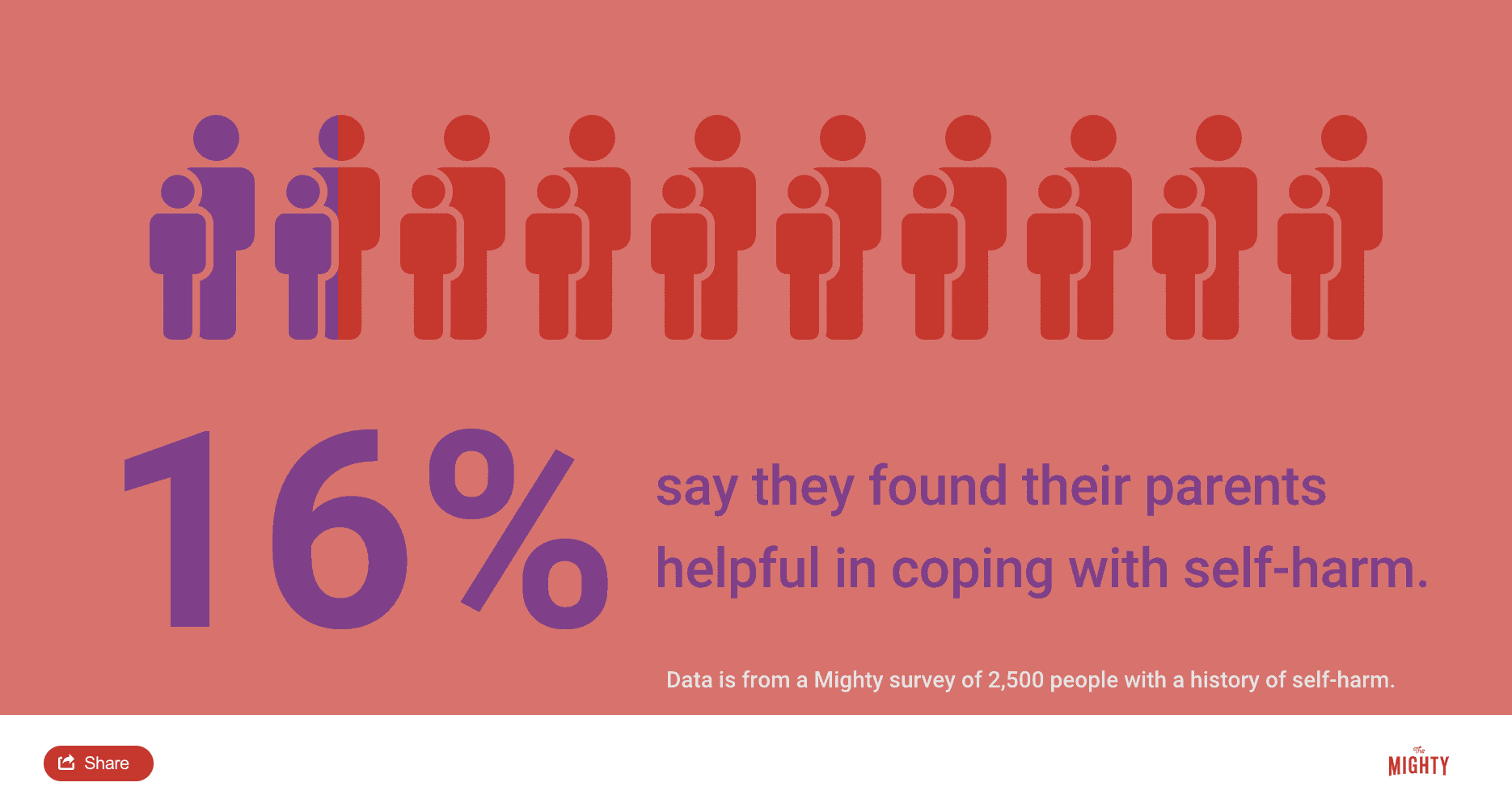

How to Provide Support at Home

Research shows that parents, in particular, are crucial to a young person’s motivation and ability to reduce self-harm.9 You can support them by modeling healthy emotion regulation skills and communication, encouraging their strengths and interests, and supporting their use of alternative coping skills. The support of a nonjudgmental, caring other can be invaluable to decreasing self-harm, so even if it feels like you’re not doing enough, small, consistent efforts add up over time.

Model Healthy Emotion Regulation

One of the biggest drivers of self-injury is not knowing what to do with overwhelming emotions. Sometimes those who self-harm don’t even know what they are feeling. To model healthy emotion regulation, get in the habit of expressing and labeling your feelings out loud. If you feel sad or start crying and your child sees this or asks why, don’t try to stuff it down. Use words to express what you’re feeling and show how you can move through sadness by talking about it and crying.

When you notice your loved one struggling with their emotions, try mirroring what you pick up and narrate for them. For example, if your child is frustrated and angry, help them put the anger into words. The more someone who self-harms can identify their emotions, the less mysterious and overwhelming they can become. In time, the emotional intensity will start to lose its power. You can also work with your loved one’s therapist to identify more specific techniques for emotional regulation and mirroring at home.

Creating a Safe Environment

Sit down together with your loved one and make a plan for safety. Contrary to what you might think, removing your loved one’s self-harm tools without their input may lead to distrust as opposed to open communication.6 Helping your child or loved one create a safe environment and a safety plan together can help reduce the risk of your loved one acting on an impulsive and getting seriously hurt. You’ll want to do this collaboratively as much as possible to balance both safety at home and empowering your loved one in their recovery. Work with your child (and their therapist) to come up with a plan to make the environment safer, such as removing harmful items from the home, to reduce risk.

Increase Protective Factors

You can also support your loved one in reducing self-harm by helping them build their protective factors. Protective factors are qualities, activities, resources and areas of success that reduce the impact of negative events. These can be internal factors such as strong academic achievement or creative talent or external factors like a strong relationship with extended family or engagement in an affirming after-school activity.

You can work with your loved one and their therapist to identify and build on their strengths and interests to open up other outlets for support during emotional difficulties. This could mean formalizing a hobby like playing soccer by joining a local community team. Your loved one may express interest in art classes, which can be a great alternative way to express emotions. It’s important to simultaneously decrease difficulties while facilitating hope by building on successes.

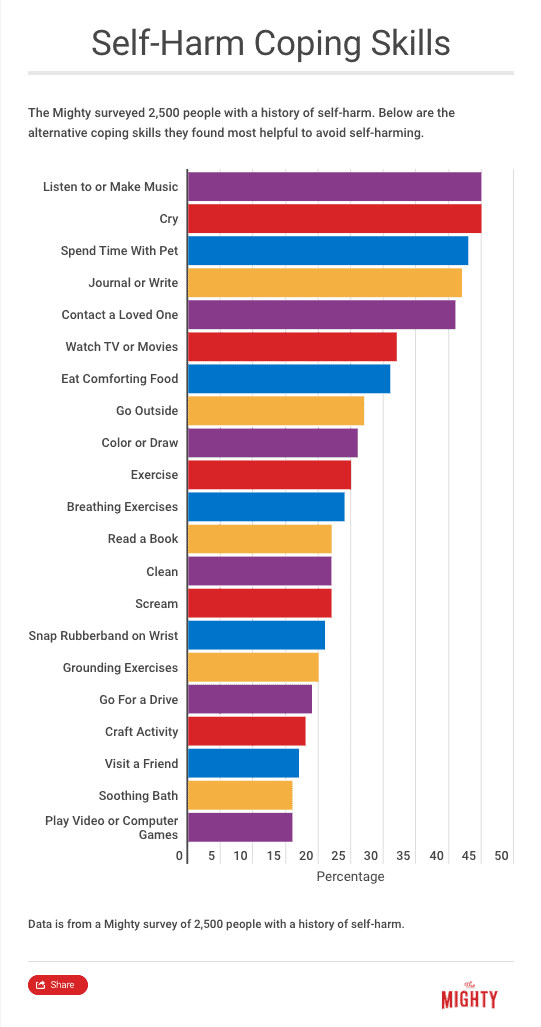

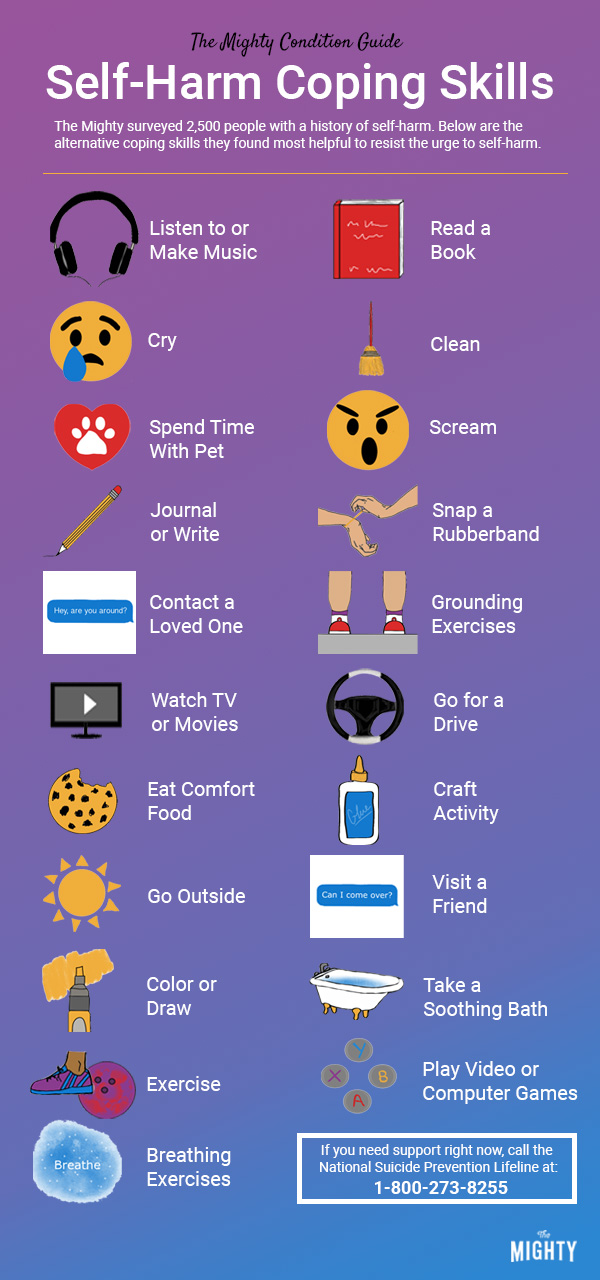

Self-Harm Coping Skills

For anyone who self-harms, they will likely need to develop alternative coping skills. These other activities reduce emotional reactivity and help your loved one temporarily tolerate intense emotion without self-injuring. You can help your child or partner find what coping skills they like and even try them together. For example, your partner may want to take a calm bath when feeling sad instead of self-injuring, but when they’re agitated, they might find it more useful to go for a run or head to the gym with you. Help them develop a list of go-to activities that might be helpful.

Know that using alternative coping skills at first will be difficult. Self-injury delivers emotional relief fast. Alternative coping skills will require tolerating difficult emotions for seconds or minutes longer than your loved one is used to. It might seem like a short amount of time to you, but the intense emotions can feel completely intolerable to your loved one. Encourage them to keep trying coping skills, especially in the beginning.

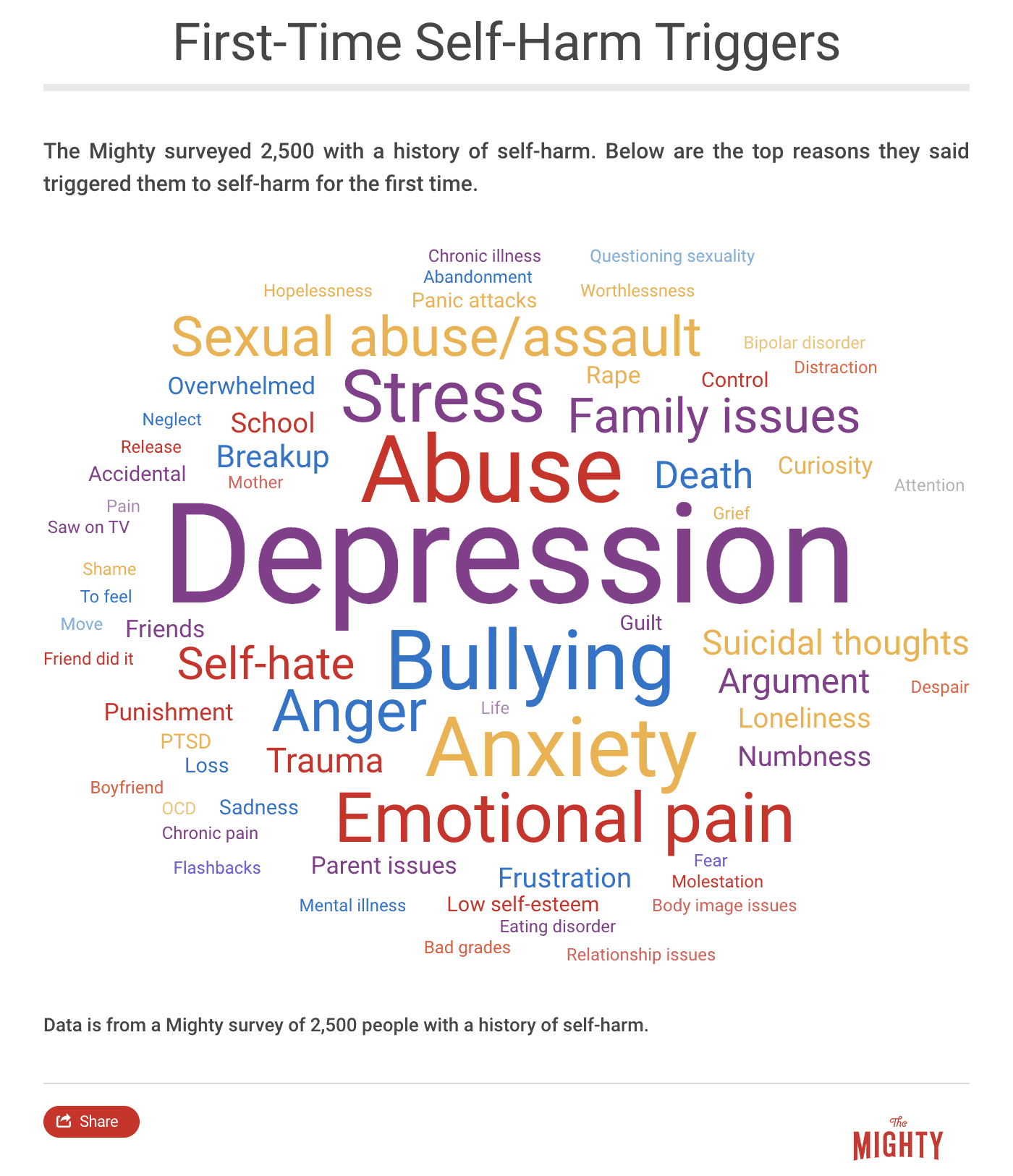

Here are the coping skills that helped 2,500 people with a history of self-harm most:

You can also find other ideas here:

- Distraction Techniques and Alternative Coping Strategies (Cornell Research Program on Self-Injury and Recovery)

- A Guide to Coping with Urges (Self-Injury Outreach & Support)

- A Guide to Coping Day-to-Day (Self-Injury Outreach & Support)

- 146 Things to Do Besides Self Harm (Adolescent Self Injury Foundation)

Using a Code Word

If your child self-harms, they may find it difficult to let you know, even if they want to reach out to you for help. It may be useful to have a code word when they feel the urge to self-harm.2 You can work with your child to pick a word — something you will both remember that won’t be confusing. When your child says this word, it’s a cue for you to stop what you’re doing and offer your child support. Work out with your child ahead of time what kind of support they would like, and honor it.

They may only want a hug with no questions asked. Maybe they want to talk with you about something they’re interested in to distract from how they’re feeling. Perhaps the code word just means you sit together on the couch and watch TV. By showing up for your child in a way that feels comfortable, you build yourself into their coping strategy and show that you can be trusted and supportive.

Self-Harm and the Internet

If you are reading about self-harm online, or are monitoring what your child reads, be aware of a few pitfalls. First, self-harm information that offers how-to instructions or shows or describes graphic images of self-harm may be triggering.4 Beware of the messages a website sends as well. Sites that hint at self-injury as a lifelong problem without solutions to decrease it are false and can be demoralizing. In addition, look out for cyber bullies who may find those who self-harm to be vulnerable targets.

On the other hand, the internet can be a great resource. It is often easier to connect with others who share similar experiences online versus in person. Many who struggle socially in-person also find comfort in online interactions. While in-person support is important, having a healthy social network on the internet is certainly better than no support.4 Find safe and productive sites to learn more about self-harm and for your loved one to chat with others in a safe space in the Resources section of this guide.

Parent and Caregiver Self-Care

For parents, partners and other caregivers of those working to decrease their self-harm behaviors, your own self-care is crucial. As the saying goes, you can only pour from a glass that’s already full. Take time to build in the support you need, too. Parents and caregivers will go through their own process while supporting someone who self-harms, which could include self-blame, a wide range of emotions and wanting to control the behavior.9 Give yourself space and perhaps engage your own therapist to work through these feelings and reactions.

Just like your loved one needs new and effective coping skills, the same practices can support your own well-being too. Make time to go out with friends and get out of the house. Maintain your physical health by eating regularly, staying on a predictable sleep schedule and get some exercise. Participate in nurturing activities like getting a massage or taking a time-out for a relaxing bubble bath.

Related: Here are some self-care ideas others in The Mighty community found helpful.

- “10 Strategies That Can Make Life as a Caregiver Easier“

- “8 Self-Care Tips for Parents Who Have No Time for Self-Care“

- “8 Self-Care Strategies for Caregivers“

- “21 Cheap, Healthy Ways to Practice Self-Care“

What to Do in a Crisis

In case of a medical or mental health crisis, it’s helpful to plan ahead so you’re not scrambling to get your loved one help in an emergency. Your child or partner might be scared of getting crisis support, for example, because emergency room doctors and some professionals don’t understand self-harm and may overreact or demean your loved one.3 Whether it’s wound care or extra mental health support, have a concrete, written-out plan in place.

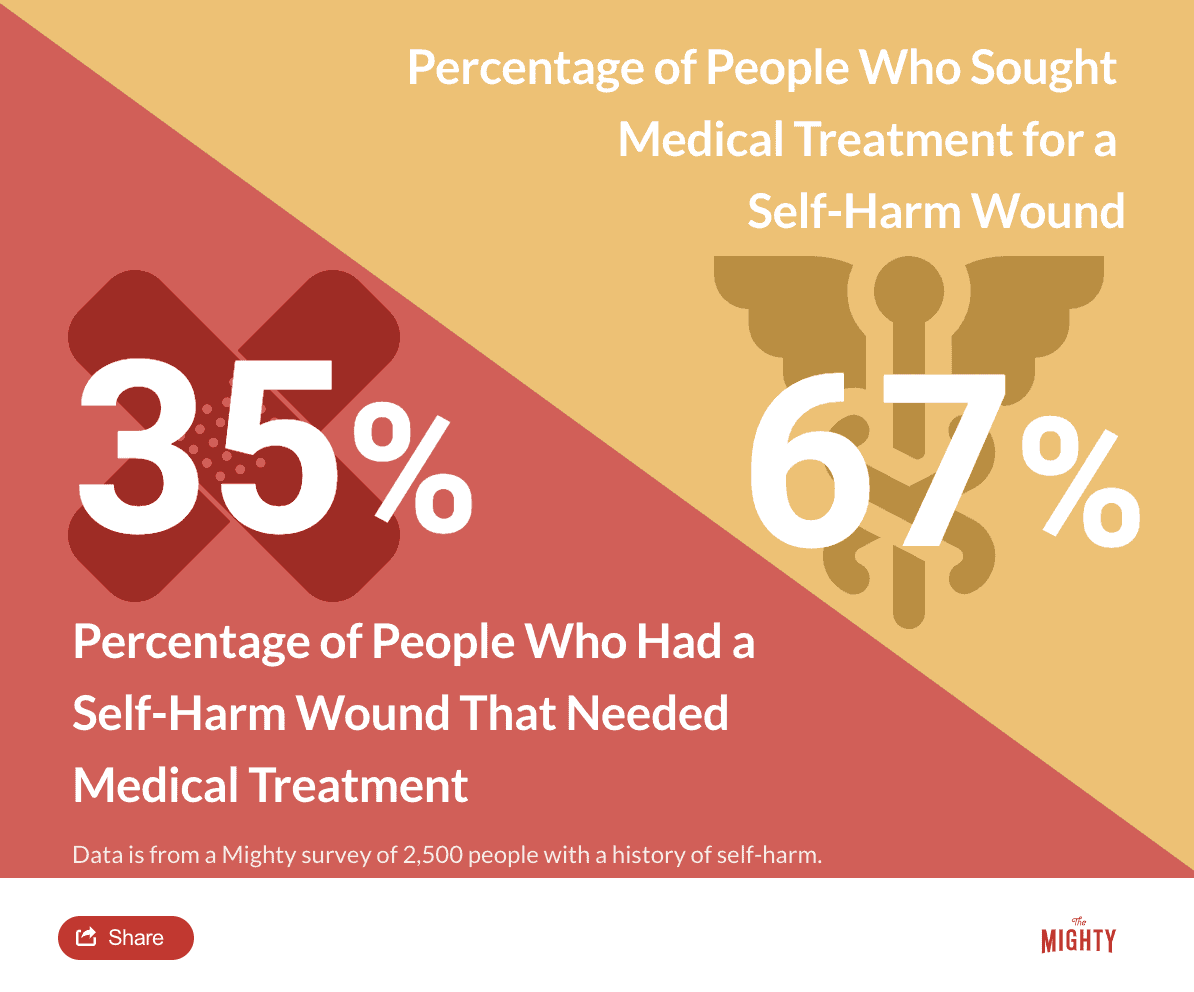

Medical Care

Proper wound care following self-harm reduces the risk of infections, other complications and even scarring. The best way to determine the best course of action is to call a medical doctor. Be sure to encourage proper basic wound care. You might even want to become certified in first-aid to stay up-to-date on the best wound care practices and to have a better sense of when a wound needs attention from a doctor.

Even if your loved one’s self-harm never rises to the level of a medical emergency, have the name of a reliable doctor on hand and become familiar with the emergency rooms in your area. It may be a good idea to interview potential doctors ahead of time to learn how familiar they are with self-harm and how they would talk to someone who self-harmed. A medical doctor who is well-versed in mental health will likely provide better care for your loved one and make them more likely to seek medical treatment.

Mental Health Crisis

Self-harm generally isn’t an attempt at suicide. However, those who self-harm have a higher risk of suicidal thoughts or may be at risk of life-threatening self-injury. If your loved one expresses wanting to die or thinks the world would be better off without them or they start giving away important possessions and saying goodbye to family, seek emergency mental health care. Stay with them. You can call your loved one’s therapist, the police or 911.

You can also encourage your loved one to use the crisis resources below:

- Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 24/7 at 1-800-273-8255

- Reach the Crisis Text Line 24/7 by texting “START” to 741-741

- Call The Trevor Project, an LGBT crisis intervention and suicide prevention hotline, 24/7 at 1-866-488-7386

- For those who are hard of hearing, chat with a Lifeline counselor 24/7 by clicking the Chat button on this page, or you can contact the Lifeline via TTY by dialing 800-799-4889

- To speak to a crisis counselor in Spanish, call 1-888-628-9454

- Head here for a list of crisis centers around the world

- For additional resources, see the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and SAVE (Suicide Awareness Voices of Education)

- For additional messages of hope, click here

Learn More About Self-Harm Recovery: Overview | For Young People | For Adults | Resources

Sources

- Behavioral Tech. (n.d.). What is Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT)? Retrieved from https://behavioraltech.org/resources/faqs/dialectical-behavior-therapy-dbt/

- Goodman, J. (2018). Self-injury [Telephone interview].

- Lader, W. (2018). Self-injury [Telephone interview].

- Lewis, S. (2018). Self-injury [Telephone interview].

- Priebe, S., Bhatti, N., Barnicot, K., Bremner, S., Gaglia, A., Katsakou, C., . . . Zinkler, M. (2012). Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Dialectical Behaviour Therapy for Self-Harming Patients with Personality Disorder: A Pragmatic Randomised Controlled Trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics,81, 356-365. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000338897

- Self-Injury and Recovery Research and Resources. (n.d.). Resources. Retrieved from http://www.selfinjury.bctr.cornell.edu/resources.html

- Sweet, M., & Whitlock, J. (2010). Therapy: What to expect. Retrieved from http://www.selfinjury.bctr.cornell.edu/perch/resources/therapy-what-to-expect-pm-2.pdf

- Whitlock, J., Minton, R., & Babington, P. (n.d.). The relationship between non-suicidal self-injury and suicide. Retrieved from http://www.selfinjury.bctr.cornell.edu/perch/resources/nssi-and-suicide-1.pdf

- Whitlock, J. (2018). Self-injury [Telephone interview].

- Whitlock, J. (2009). The Cutting Edge: Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in Adolescence. ACT for Youth Center of Excellence Research Facts and Findings,1-9. Retrieved from http://www.selfinjury.bctr.cornell.edu/publications/2009_1.pdf

- Whitlock, J., & Purington, M. (2013). Respectful curiosity. Retrieved from http://www.selfinjury.bctr.cornell.edu/documents/pm_respectful_curiosity.pdf

- Whitlock, J., & Purington, M. (2013). Positive Communication Strategies. Retrieved from http://www.selfinjury.bctr.cornell.edu/documents/pm_positive_comm.pdf