The Loneliness I Wasn't Prepared for After I Finished My Cancer Treatment

When I was first blindsided by my cancer diagnosis six years ago, I was, as cancer diagnoses go, fortunate. My beloved wife happens to herself be a doctor, and while she is not an oncologist she is of course generally much more knowledgeable about these types of matters than would be a lay person. I am also fortunate to still have both of my parents alive and well – if a bit nutty – to provide additional love and support. And, as hard to believe as this may seem, I am also blessed to have compassionate, loving and, not unimportantly, geographically-close in-laws who are extremely supportive.

As if all of that were not enough – and I say this knowing full well that so many people must face this awful disease with a fraction of the support, if any, that I have had – I also live in the New York City area. Although that is certainly a mixed blessing, it does put within a short train ride many of the world’s foremost experts on the cancer that my body elected, without my consent, to which to subject itself.

Consequently, I was able to be rather specific (read: highly picky) about whom I would entrust with my cancer and the treatment thereof.

Consequently, over these six years, I have been more or less enveloped in people who are quite involved – some might say, overly so – in how I am dealing with all of this cancer business. At no point was this “It Takes A Village” reality more apparent than when I finally had to acquiesce to my oncologist’s requests and undergo several months of chemotherapy. Not only did the rounds of infusions result in more well-wishes, expressions of concern and visits from my parents from the Sunshine State, but I was also very closely monitored and tended to by a phalanx of superb oncology nurses, M.A.s., N.P.s, P.A.s and other persons whose abbreviated titles I have either forgotten or, more likely, never really knew. If there were one negative emotion that I could steadfastly attest to not experiencing during all of this, it was loneliness.

And yet, no sooner had the “I finished chemo bell” stopped ringing than things changed completely. It was not as though I suddenly had been forgotten or that no one cared, but nevertheless a sea-change both within me and among those around me occurred for which I had no preparation nor sense of anticipation.

The most immediately noticeable of all these changes was that I was finished with my regular toxic infusions. Naturally, one would – and should – consider the cessation of the intravenous absorption of regularly-scheduled poisons to be a step in the right direction. And it was. What was a decidedly less positive development, however, was the absence of those wonderful nurses and others who had helped me through all of it. And not just physically – but importantly through the psychological struggles that come with seeing oneself at the mercy of a disease and horrific concoctions used to combat it. These nurses and others were true pros, who made me feel as though what I was enduring would not be for naught and that I would leave their care a stronger person, physically as well as emotionally.

At the same time, while perhaps less obvious if not just as psychologically impactful, was the end of the attention that had been focused on me and what I was experiencing. Although I do love the spotlight, I can genuinely state that being the focal point of attention for this reason was not an uplifting experience. I know there are those who love being sick – a sickness in and of itself – but I do not count this among my many issues. Nevertheless, it is as if one is going from 60 MPH to zero in an instant: One moment everyone is concerned; the next, everyone behaves as if everything is fine. Nothing to see here.

Although I understand why it is common, and perhaps even necessary, for those who love one suffering from cancer to themselves be able to get away from its terribleness, the unfortunate reality is that finishing treatment for cancer is not the end of the story. At best, to paraphrase Winston Churchill, it is perhaps the end of the beginning. So many cancer survivors with whom I have spoken have stressed this point to me – finishing treatment merely marked the start of a new, but not necessarily better, chapter in their ongoing journey with cancer. And that is from people who, unlike me, were “cured” of their cancer. My cancer, as I knew from the day I was first diagnosed, was not of the curable variety. Walking out of the infusion center after that last day of treatment did not allow me to put chemo in the proverbial rearview mirror. No. It’s along for the ride from here on out.

Yet most people do not seem to be able to grasp that cancer never really leaves its reluctant hosts. Cancer survivors or endurers or whatever term one prefers may well look fine. They may even seem fine. But for many of us, we are not really fine. The trauma of staring down a terminal illness and enduring the attempts to forestall its progress have untold ramifications, both physical and emotional. There is for many of us a sense that we are no longer physically whole; that our bodies have been irreversibly compromised and that we are only at a brief way-station before the next – and potentially worse – onslaught occurs.

And this is not just in our heads: We are constantly reminded of this dreaded potential reality by the ever-ongoing need for more scans, more tests, more labs, more appointments, more doctors. And with each of these “more’s” comes renewed anxiety and fear and dread. And, perhaps most difficult of all, more loneliness. For at the end of the day, it is you, the one with cancer, who must have the scan performed or the blood drawn or the lymph nodes examined. It is you, cancer‘s unwilling companion, who must contemplate life and its brevity. And it is you, cancer sufferer, who sits alone in the wee hours of the night worrying over all of these things over which no one has any control.

I am, as I said at the outset, about as lucky as a person with cancer can hope to be. But I know now that despite all of the love and friendship and excellent care that I have been afforded, at the end cancer is a solitary experience. This revelation is sometimes the hardest part of cancer of them all, and the one for which almost none of us are ever prepared.

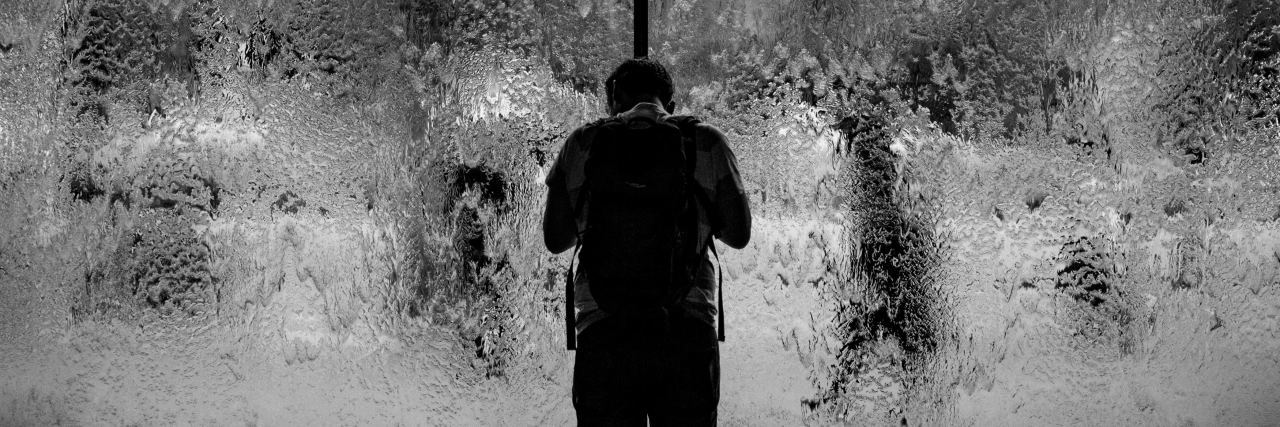

Lead photo courtesy of Unsplash