Every time my mother arrives at our house, my daughter asks, “Where’s Pop-pop?” She knows the answer but craves the exchange, and its subject. They both do.

“Oh Erin you know. Where is Pop-pop?” my mother replies.

“Pop-pop’s in heaven,” Erin answers.

I don’t know if Erin knows what the answer means. I am not sure I do either, but it’s something she feels she must ask if only to communicate that she’s thinking about him. Erin,18, has an autism spectrum disorder which involves significant cognitive, speech and language impairments. Very often asking a question is her way of making a statement, expressing a desire or sharing an emotion.

Until recently Erin had never seen my mom without my dad, who passed away last summer. No one really ever had. They went together like Ernie and Bert, Anna and Elsa and all the other logical pairs in Erin’s life. For her, and the rest of us, the singularity of my mother’s presence is striking. Something is missing and Erin notes the absence with a question and their well rehearsed script.

Unlike my typically developing children, who feel that mentioning my dad might make my mom sad or remind her that he is no longer here, Erin plows right through. She really knows no other way to be. As the rest of us wade through grief in our own way, I’ve begun to feel that maybe what has been labeled as an “impaired” way of being is less “a deficit” and more a strength, at least when it comes to processing the death of someone you love.

My father was diagnosed with an aggressive form of dementia four years ago. The disease took its toll in progressive stages: hallucinations, irritability, forgetfulness. A lifelong teacher, he often mistook my brothers for bus drivers and delivery men and my sons for former students. While he never forgot the love he felt for my mom, his wife of 51 years, there were moments when my mother, sister and I were interchangeable.

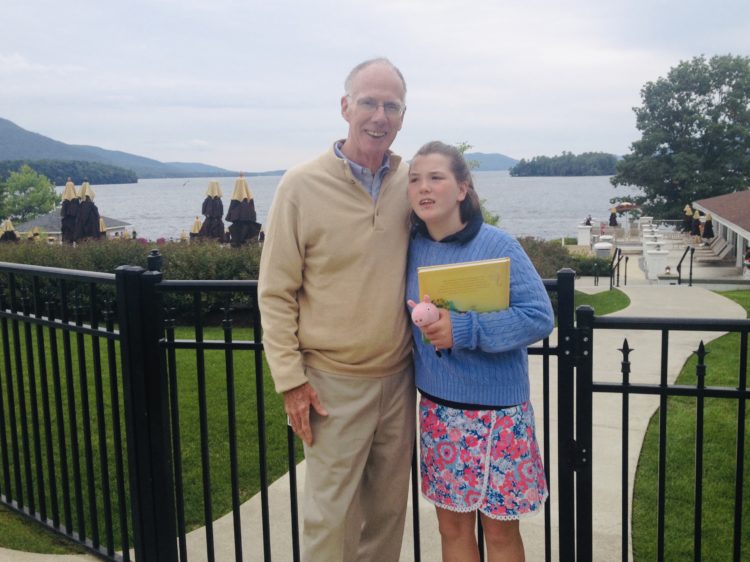

He never forgot Erin, and their relationship never missed a beat. She did not know he was losing hold of his world. She only knew that she loved him and that they loved so many of the same things: car rides, country music, comfort food.

While my dad always embraced Erin’s difference, as his disease progressed, their connection seemed to intensify. Erin communicates physically. She is big on hugs and squeezes. She hugged my dad a lot and he, never a big talker, hugged back hard.

She never grew impatient with his increasingly quirky behaviors. She did not object to his opening and closing the front door a hundred times a day. She saw no issue in his smothering his pancakes in ketchup. She did not mind that he sometimes walked in circles around our driveway and asked repeatedly to go for a drive. She finds great satisfaction in closing open cabinets, drawers and bottle caps, follows no hard and fast rules when it comes to food consumption and understands that sometimes a walk or a drive to no place in particular is just what you need.

Erin visited my dad in hospice care at his home. She crawled up on to the bed beside him and rubbed his arm — two bodies always on the go suddenly joined in an unfamiliar but content stillness. She whispered, “Pop-Pop is sleeping,” and stared as if in a trance.

In the moments Erin has seen me upset about my father’s death, she asks, “Are you sad?” She knows what sadness is; for her I believe it is the absence of his presence and the lack of their so very tangible exchange. She seems to process this by conjuring his memory in the mundane moments she shared with him.

“Pop-pop likes this song.”

“Pop-pop likes sweet potatoes.”

“Pop-pop likes blueberry pie.”

Like many who live with neurological and language disorders, Erin does not use the past tense. I start to correct her, “Yes, he likes — actually, he liked — OK, fine, he likes.”

Erin communicates as she lives only in the present and implores all around her to do the same.

Erin did not attend the funeral, because it would have been hard for her to sit in the wooden pew and listen to unfamiliar faces lecture about life and love. She would have wanted to leave with my mom and go to the book store. She would have wanted my undivided attention. My attention would have been divided that day. I had to be there for my mom and the boys. I had to deliver a eulogy in which I talked about Erin and my dad. How he never considered her to be “impaired” or to have a “disability” in any way. He thought she was bright, brilliant and funny.

“She doesn’t miss a trick,” he’d often say.

I think he’s right.

Photo submitted by contributor.