U.K. Study Suggests Suicide Risk Skyrockets Month After Hospitalization for Self-Harm

Editor's Note

If you experience suicidal thoughts or have lost someone to suicide, the following post could be potentially triggering. You can contact the Crisis Text Line by texting “START” to 741741.

A new study published on Wednesday tracked suicide risk among nearly 50,000 patients hospitalized for self-harm during a 15-year period. Like previous research, this study found a major increase in suicide risk in the month and year following a hospitalization, indicating the need for better mental health support and a hard look at how hospitals treat mental health patients.

What the Study Found

The Lancet published the results of a study conducted in the U.K. by researchers who investigated suicide risk based on different patient characteristics. To do this, researchers looked at data on “non-fatal self-harm,” hospitalization and suicide rates among nearly 50,000 patients from three England hospitals during a 16-year period. They also looked at suicide risk based on gender, age and socioeconomic status among those hospitalized for self-harm.

Of the nearly 50,000 people whose data was included in the study, 703 people died by suicide during the study period. Nearly 36% of those who died by suicide died within a year of discharge from a hospital, including an elevated risk within one month from discharge. The study suggests the suicide rate among those hospitalized for self-harm is nearly 200 times higher than the general population within a month following hospitalization.

Age, gender and number of hospitalizations for self-harm also appeared to correlate with suicide risk. The suicide rate was highest in this study among those who were at least 55 years old, which tracks with the rising suicide rate in the United States. Males were also three times more likely to die by suicide after hospitalization for self-harm compared to females. Previous research suggests males are more likely to engage in more potentially lethal forms of self-harm, which may contribute to higher suicide risk.

“The risk of death by suicide is very high immediately after patients leave the hospital which means that, in addition to aftercare, there should be a safety plan in place for patients,” study author Galit Geulayov, Ph.D., Centre for Suicide Research, Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford, told The Mighty via email, adding:

This safety plan is designed to address immediate suicidal crisis when a patient return to the community. It should be negotiated with the patient need and include discussion about risk of further self-harm, help the patient identify ways to cope with further crisis (e.g. problem solving techniques), help them identify sources of support (e.g. family member, friends) to assist if and when a crisis emerges, and identify relevant services which can help the patient stay safe.

Study Limitations and Considerations

It’s important to note that this study did not differentiate between what some researchers call non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) versus suicidal self-injury (SSI). This can be an important distinction because the intention behind the behavior is very different. With non-suicidal self-harm, the intention is to regulate intense experiences to feel better, not die by suicide. Suicidal self-injury, the intent may often be lethal. Therefore a patient hospitalized for self-harm with the intention to die by suicide may really be making a suicide attempt, which may require a different risk assessment.

“While non-suicidal self-injury is physical and it looks violent and of course that is true, it doesn’t require the same psychological capacity as it requires to conceive of [suicidal behaviors],” Janis Whitlock, Ph.D., MPH, director of the Cornell Research Program on Self-Injurious Behaviors and co-author of the book “Healing Self-Injury,” previously told The Mighty. “That’s a different psychological step.”

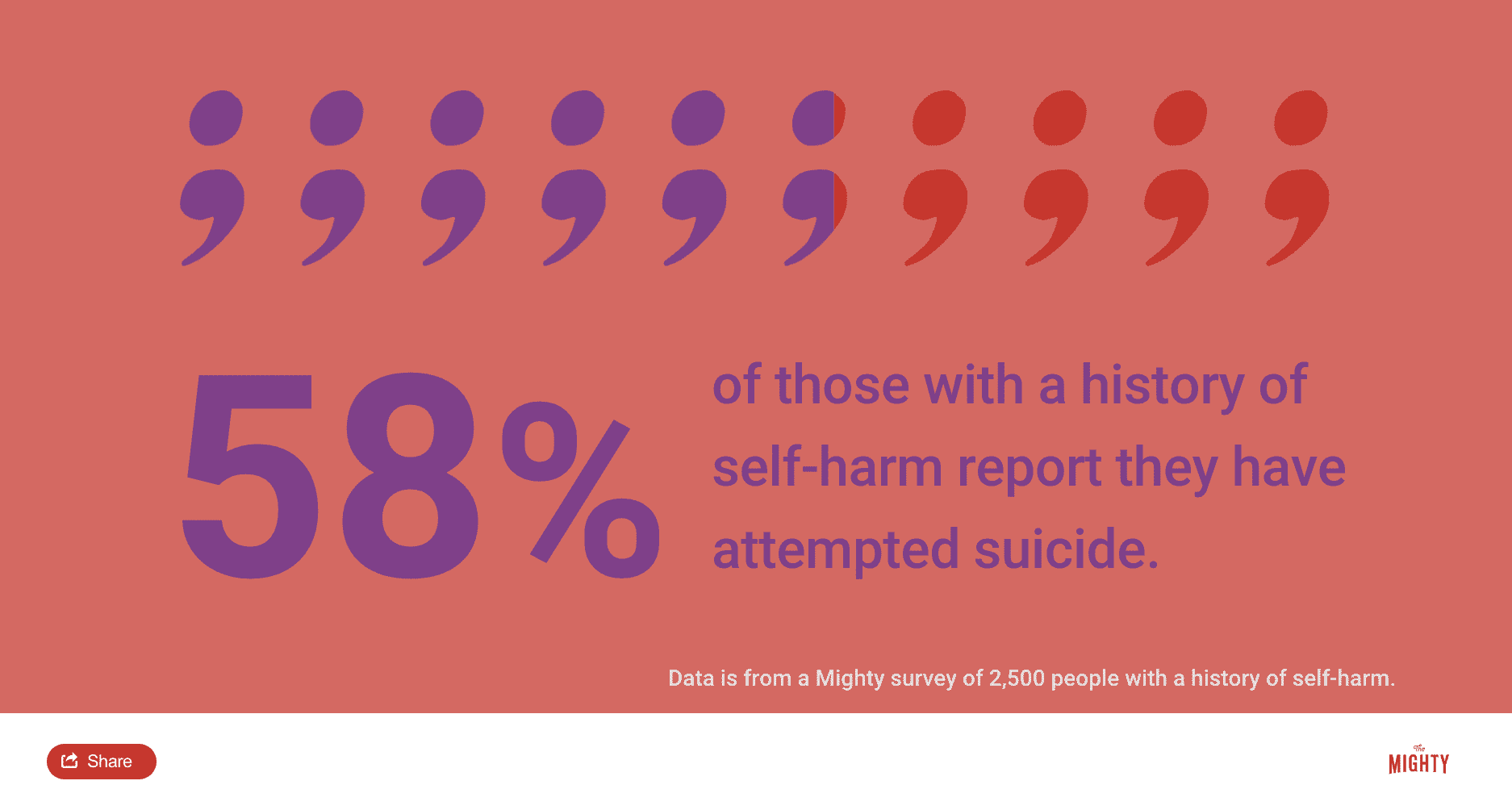

Confusing the two types of self-harm can also perpetuate the myth that self-harm is always a suicide attempt. Non-suicidal self-injury is associated with increased suicide risk — in a Mighty survey of 2,500 people with a history of self-harm, 58% said they attempted suicide at least once — but it is usually not a suicide attempt. People may use non-suicidal self-harm for a variety of reasons, most often to regulate intense emotions or manage difficult situations. To confuse non-suicidal and suicidal self-harm can create additional stigma and lead to improper treatment.

However, Dr. Geulayov said differentiating between non-suicidal and suicidal self-injury is more common in North American research as opposed to in the U.K., where this study was conducted, and other European countries. Geulayov also said this and other research suggests that suicide risk is elevated regardless of the motivation for self-harm and it’s important to improve support across the board.

“Our research suggests that motivation and intention are complex to determine and that individuals who self-harm may do so for many purposes,” Geulayov said. “Also, findings from the present study and from other similar studies show that all patients who present to hospital for self-harm are at a high risk of subsequent suicide and that this risk is much higher than that expected in the general population, suggesting that it may not be in patient benefit to treat specific methods of self-harm as non-suicidal.”

What This Research Means for Suicide Prevention

Wednesday’s study builds on a growing body of knowledge about increased suicide risk after leaving the hospital. While the reasons vary, a Mighty investigation found hospitalization for suicidal ideation often made people feel worse or more hopeless. For example, a Mighty survey of 1,622 suicide attempt survivors found that 42% of those hospitalized after a suicide attempt said they didn’t leave the hospital in a better state than when they went in.

“When people are hopeful, they’re not suicidal, but the system makes you feel really hopeless. The cultural attitudes about suicide make you feel hopeless,” Jess Stohlmann-Rainey previously told The Mighty. “So basically every message you get when you’re in that place is a message about hopelessness instead of something else. There’s a lot of things connected to that.”

Though no single risk factor can predict or prevent suicide, understanding who is more at risk and when can help experts conduct better assessments and provide more effective services to those who need support. According to this study’s authors, this is especially true in hospitals, where some people who self-injure are released without any psychological assessment at all. Increased suicide rates in the month and year following hospitalization for self-harm also underscores the need to take a closer look at how patients are supported during and immediately following discharge.

“We should focus on the services which are offered to patients when the attend clinical service including the in-hospital psychosocial assessment, follow-up care after discharge, and their safety plan upon discharge from hospital,” Geulayov said, adding:

These areas require further research effort and evaluation. The services which are offered to patient who present to hospital for self-harm may vary across the country and we do not have good quality and systematic data through which to identify patients’ care pathways after their discharge. Such data would be valuable for identifying potentially effective interventions. Further research is also required to improve uptake of in-hospital psychosocial assessment in this patient group.

If you need support right now, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or reach the Crisis Text Line by texting “START” to 741741.

Header image via KatarzynaBialasiewicz/Getty Images