How to Get a Parkinson's Diagnosis

Editor's Note

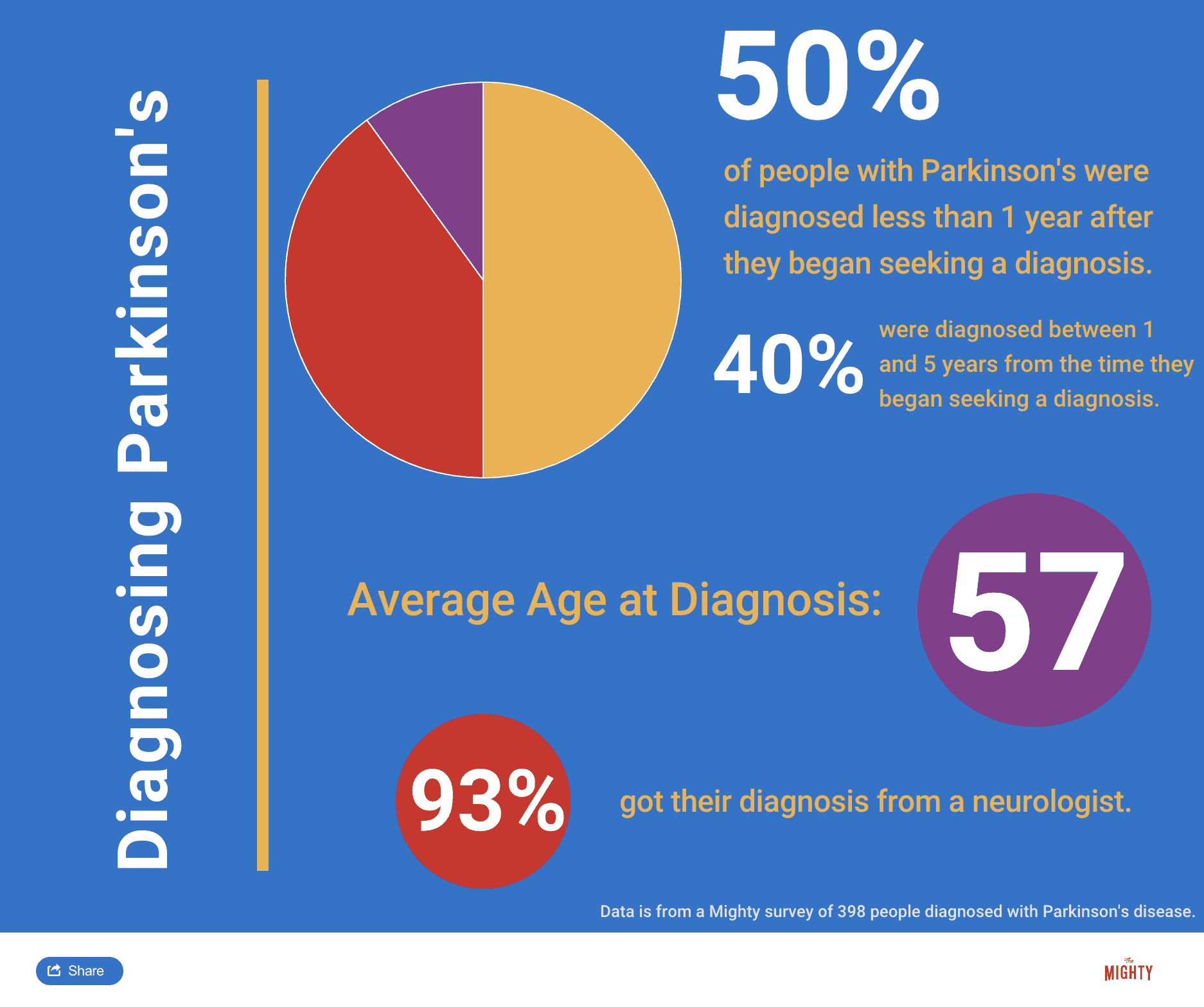

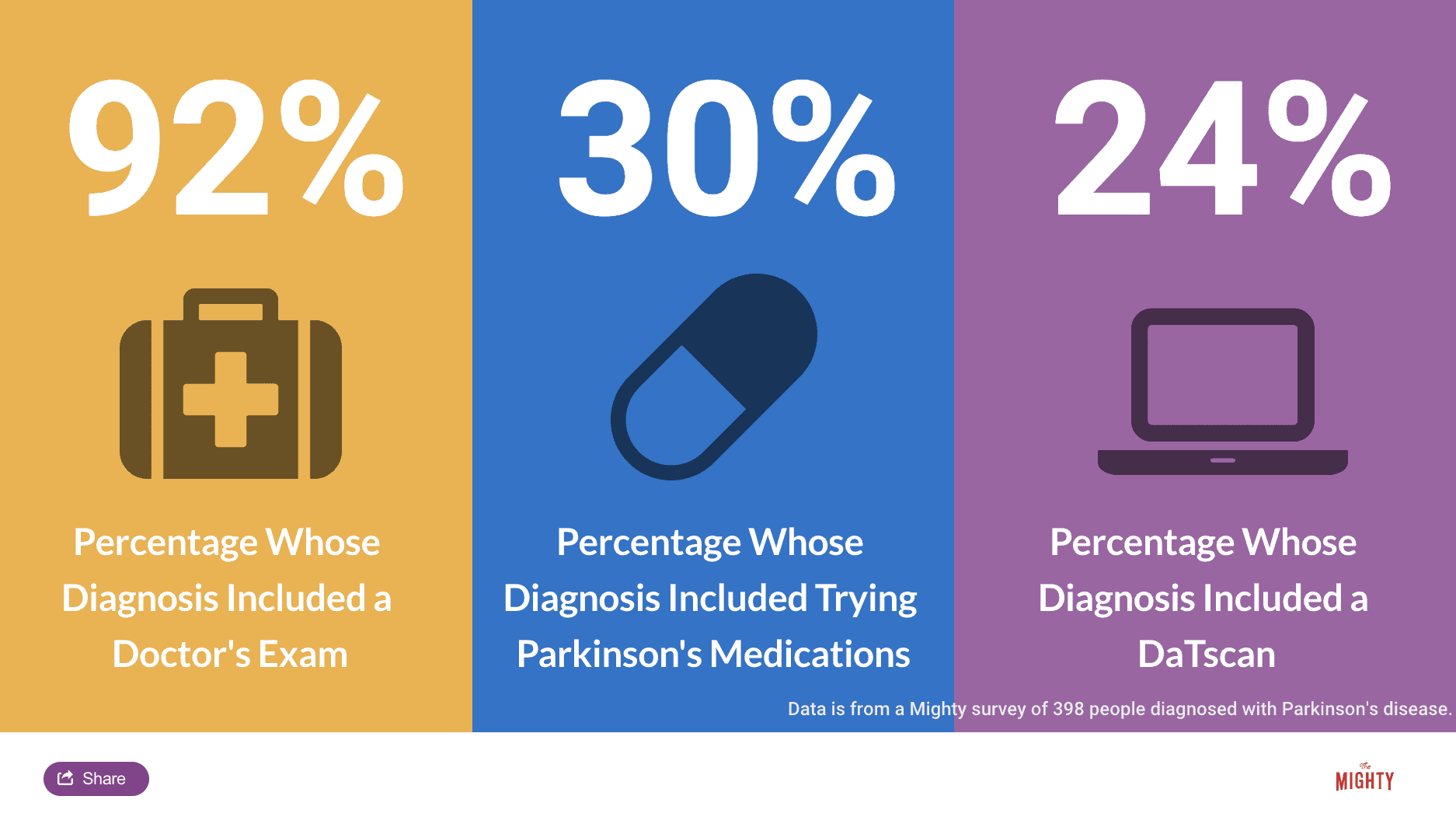

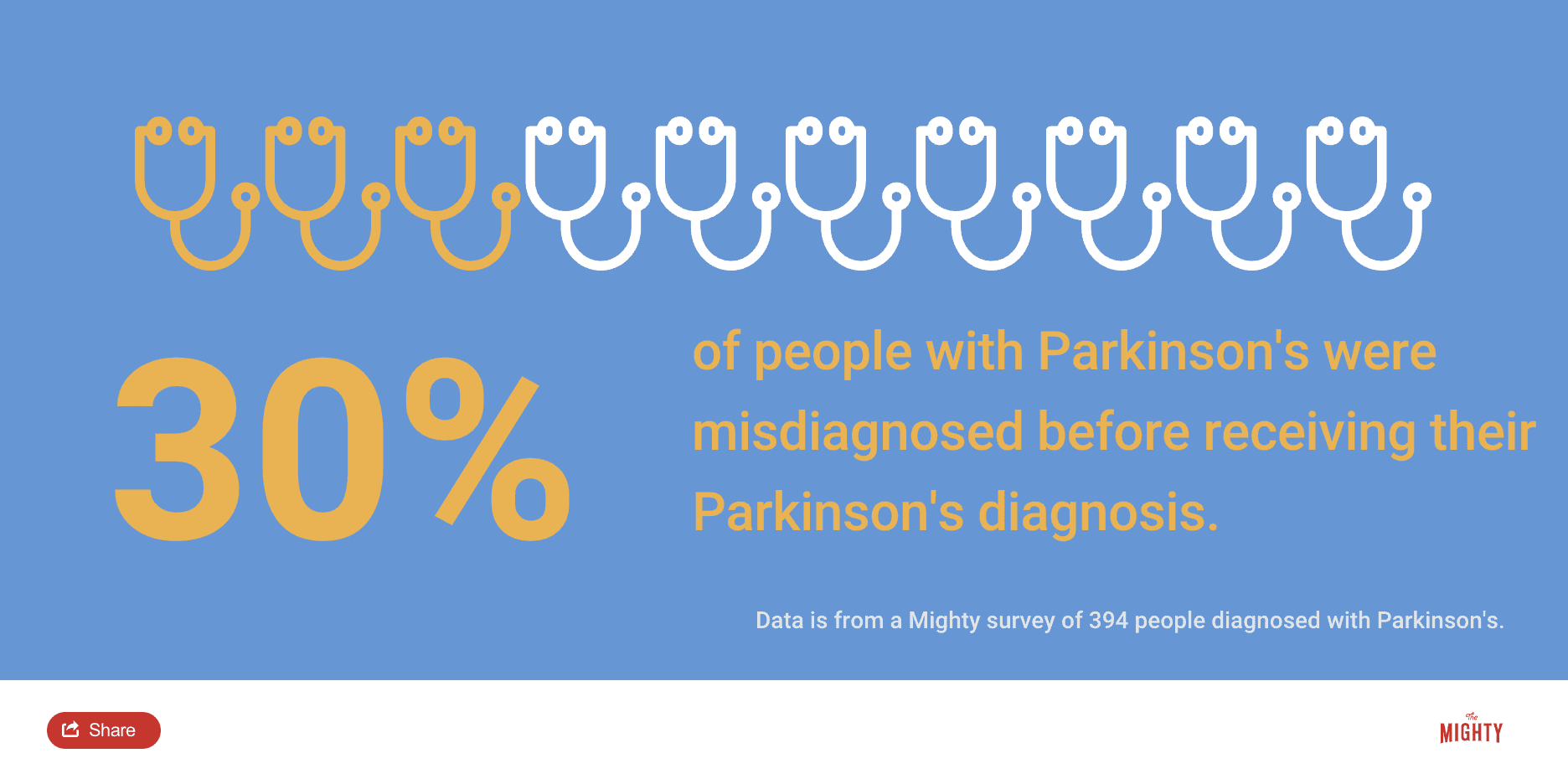

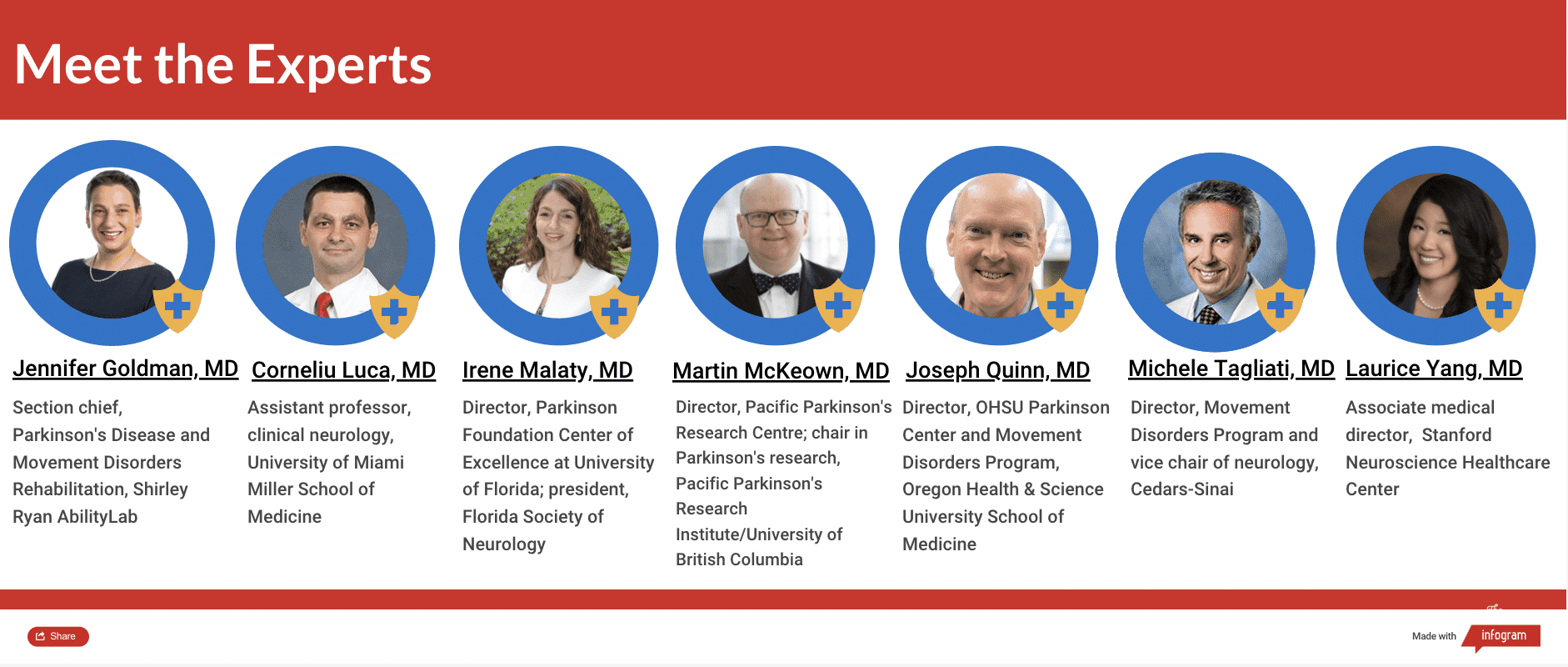

The Mighty’s Condition Guides combine the expertise of both the medical and patient community to help you and your loved ones on your health journeys. For this guide, we interviewed seven medical experts, read numerous studies and surveyed nearly 400 people diagnosed with the condition. The guides are a living document and will be updated with new information as it becomes available.

Other sections of this Condition Guide:

Overview | Symptoms | Treatment | Resources

What you’ll find in this section:

Finding a Doctor | What Parkinson’s Diagnosis Criteria Do Doctors Use? | What to Expect at the Appointment | Conditions That May Be Mistaken for Parkinson’s Disease | Other Challenges of Diagnosing Parkinson’s Disease

This section was medically reviewed by Brent Bluett, M.D.

Understanding Parkinson’s Disease: Getting a Parkinson’s Diagnosis

Once you start noticing some changes in your body that impact your daily life or are just simply bothersome, you should begin the process of figuring out if you have Parkinson’s disease. It may seem like a daunting undertaking, but don’t let fear stop you. Once you are diagnosed, you can start treating your symptoms and learning strategies that will help you feel better.

What is Parkinson’s Disease?

Finding a Doctor

Your general or family doctor may be familiar with Parkinson’s disease and may be able to put the pieces together when they examine you. The more experience a doctor has in Parkinson’s disease, the better.10 However, the best type of doctor to get a diagnosis from is a movement disorder specialist — a neurologist trained in conditions that cause movement problems, like Parkinson’s disease, Tourette syndrome and dystonia, which causes muscle contractions. These doctors know the latest research and treatments and they know which symptoms to look for when making a Parkinson’s diagnosis.

If you go to your regular doctor and they’re not sure about diagnosing you, you may be referred to a general neurologist or a movement disorder specialist. Or you can find a specialist on your own — you can research to find one in private practice or at a larger university-affiliated medical center.20 Some tools that can help begin your search include:

- The Parkinson’s Foundation’s resource map, which allows you to search for PD care and community organizations in your area

- The Parkinson’s Foundation Helpline: Call 1-800-4PD-INFO (473-4636) or email helpline@parkinson.org for a referral

- The International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society’s movement disorder specialists directory

No matter who you see, don’t be afraid to seek a second opinion with a movement disorder specialist if you feel like your doctor isn’t taking your symptoms seriously or isn’t knowledgeable about Parkinson’s disease.

What Parkinson’s Diagnosis Criteria Do Doctors Use?

Until the 1980s, there was no formal diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Beginning with James Parkinson’s 1817 article, “An Essay on the Shaking Palsy,” and Margaret Hoehn and Melvin Yahr’s description of the five stages of motor progression in 1967, scientists focused on the unique (and visible) ways Parkinson’s disease affects movement. A few scientists also noted non-motor symptoms like issues with automatic body functions, such as heart rate and blood pressure.

With the discovery in the 1950s of levodopa, a drug that gets turned into dopamine in your brain and thus replaces some of the dopamine that is lost due to PD, and the discovery of how dramatically levodopa improves motor symptoms, the medical community continued to focus more of their efforts on defining and treating Parkinson’s as a motor condition.7

The Diagnostic Criteria Used Today

In 2015, a Movement Disorder Society task force proposed a set of criteria that became known as the Movement Disorder Society – United Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS), which includes non-motor symptoms in its criteria.9

The new criteria requires you to have slowness of movement, plus either a rest tremor or rigidity. It also requires that you do not meet any criteria in a list called “absolute exclusion criteria.” This list of symptoms indicates you most likely do not have PD or that you may have an “atypical parkinsonism” — disorders that resemble Parkinson’s disease but are ultimately different. If you meet any of those requirements, PD is ruled out. For example, one absolute exclusion criteria is if you are taking a drug that is known to cause Parkinson’s-like side effects.

Next, you must meet at least two of the following four criteria:

- Dramatic improvement of motor symptoms when you take the gold-standard Parkinson’s medication called levodopa

- The presence of dyskinesia (involuntary movement) as a result of taking levodopa — dyskinesia is a possible side effect of levodopa among people with PD

- Rest tremor, meaning your tremor occurs when the body part is at rest

- Loss of smell, or if you have a test called MIBG scintigraphy and it indicates that you have autonomic dysfunction, which is when your autonomic nervous system doesn’t work correctly, leading to issues with things like heart rate and blood pressure.

Finally, if you meet criteria in a separate list in the MDS-UPDRS criteria called “red flags,” you must also meet the same number of criteria among the four above. (If you have two red flags, then you must meet two of the criteria above, and so on.) There are 10 red flags in the list and all indicate that you might not have Parkinson’s. For example, if you don’t have any of the common non-motor symptoms despite having PD for five years, then in order for PD to still be considered, you must also have at least one of the four criteria above. If you have five or more red flags, that would point to you likely not having Parkinson’s disease because the signs you don’t have PD outweigh the signs you do.

The MDS-UPDRS also recognizes there is a “prodromal” phase of Parkinson’s, early non-motor symptoms and signs of PD that occur before you start noticing motor symptoms. While non-motor symptoms are not necessarily “formally” part of making a PD diagnosis, they can help confirm if your doctor suspects Parkinson’s.16 In fact, you may not even realize some non-motor symptoms are related to Parkinson’s disease.

What to Expect at the Appointment

To make a Parkinson’s diagnosis, your doctor will look for the three main motor symptoms: bradykinesia (slowness of movement), tremor and rigidity. Remember, not everyone with Parkinson’s disease has a tremor. They will also ask questions and examine you to see if there are possible other explanations for your symptoms besides Parkinson’s.

The doctor will ask you questions and look for Parkinson’s signs like:

- If you have a resting tremor, meaning your tremor appears when your limb like an arm or leg is still

- If your tremor and/or other movement issues occur on one side of your body only

- If your handwriting has become very small

- If you have issues with balance

- If the way you walk has changed; for example, you are taking small steps or having trouble turning

- If you have stiffness, aka rigidity, in your arms or legs; for example, you don’t swing your arm when you walk

- If you have difficulty with fine motor movements like combing your hair or brushing your teeth

- If your voice has become softer or more difficult for others to hear

To assess your non-motor symptoms, your doctor may ask you questions about:

- If you’ve lost your sense of smell

- If you experience constipation

- If you talk or act out dreams while you sleep

After asking you questions about these symptoms and observing your movement, your doctor may be able to diagnose you with Parkinson’s immediately. However, since the diagnosis is clinical, meaning it’s based on signs and symptoms rather than lab tests or imaging, you may exhibit signs that make it more difficult for your physician to make a concrete diagnosis. In this case, there are a few more strategies doctors use to make a Parkinson’s diagnosis.

Watching Your Progression

After examining you, your doctor might suspect you have Parkinson’s, but ask you to follow up over the next several years, so they can observe if or how your symptoms have progressed.8 Since Parkinson’s is a progressive disease, examining you again over time may also give you time to present with hallmark symptoms that weren’t noticeable before.

For example, maybe you went to your doctor because you are having sleep issues like acting out dreams, but your motor symptoms are very mild or almost unnoticeable. Your doctor likely won’t want to diagnose you with Parkinson’s based on your sleep issues alone, so they might ask you to come back in six months to see if your other symptoms have developed. If your symptoms don’t get any worse or if they improve on their own, you may have another medical condition.

DaTscan

There is no singular test to definitively use to determine if you have Parkinson’s disease. However, a test called a DaTscan can help confirm if you have a form of Parkinson’s by showing if you have lost dopamine transporters in your brain, which normally help in the process of how your brain stores and releases dopamine. The European Medicines Agency approved the DaTscan for use in 2000, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved it in 2011.

In a DaTscan, a radioactive drug called ioflupane I123 is injected into your bloodstream through an IV line. Then, three to six hours later, a technician takes photos of your brain using single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging — basically an MRI-like device where you lie down on a table with your head in large imaging equipment. The ioflupane I123 drug lights up the areas in your brain where dopamine transporters collect. A healthy brain image will show a symmetrical, “comma”-type pattern of dopamine transporters, while a brain with Parkinson’s will show a small, abnormally-shaped pattern.15 Similar to other radioactive medical tests, like X-rays, exposure to radiation is a risk of the procedure. Prior to the scan, you should receive a drug that blocks your thyroid from absorbing the radiation.3

There are a few limitations to DaTscans. It can only tell you if you have a form of Parkinsonism, which includes PD and atypical parkinsonism (i.e. progressive supranuclear palsy, Lewy body dementia, corticobasal syndrome, and/or multiple system atrophy). Although each of these conditions have unique symptoms that doctors can tell apart, they are all associated with a loss of dopamine. So the test can only reveal if there is a loss of dopamine, and cannot tell you which of those conditions you have. It also can’t tell you how advanced or severe your disease progression is.18

If your doctor is already fairly certain you have Parkinson’s disease, a DaTscan will simply confirm their suspicion. On the other hand, if your doctor is having trouble determining if you have Parkinson’s disease or a separate condition, like essential tremor, then a DaTscan may be useful.

A DaTscan is not required in order to diagnose Parkinson’s disease, so you should discuss whether or not you should get one with your doctor. DaTscans are covered by Medicare and Medicaid, and may be covered by other insurance plans. Without insurance, DaTscans cost about $2,500.4

Trying Parkinson’s Disease Medications

One of the features of PD is that it will significantly and consistently improve when you begin taking medication that targets your dopamine system.10 Your doctor may ask you to try taking Parkinson’s medication, like carbidopa-levodopa, to help confirm a PD diagnosis. Levodopa is a drug that is converted into dopamine in your brain, replacing some of the dopamine you lose due to the disease. Levodopa is frequently paired with carbidopa, which helps prevent levodopa from breaking down before it reaches your brain. Your doctor will observe if carbidopa-levodopa helps your motor symptoms. Carbidopa-levodopa is typically very effective at treating motor symptoms, so a significant response to the medication used to treat it helps confirm the diagnosis. Parkinson’s medications are generally very safe and the risk of taking them is low, while the benefit is great because it might help if you do have Parkinson’s and improve your mobility.10

Related: What you can do before you see your doctor next.

Conditions That May Be Mistaken for Parkinson’s Disease

There are a few conditions that may be confused with Parkinson’s disease. These conditions can cause similar symptoms, and because there is no definitive test that proves you have Parkinson’s disease or any of these “similar” conditions. As you might imagine, this can make it challenging at times for doctors to figure out which condition you have. A few of the most common conditions that might look like Parkinson’s are:

Essential Tremor

Essential tremor is a neurological condition that typically causes a tremor of both hands, and possibly other body parts, when the limb is at rest and also when the body part is held against gravity (for example, holding your arm out). It is believed to be caused by abnormal functioning of the thalamus, a part of the brain that sends signals related to movement. Many cases are caused by a genetic mutation that is passed down among families.

This tremor differs from the Parkinson’s tremor in a couple key ways: it worsens when you voluntarily move the affected body part and usually occurs on both sides of your body, though one side may be more affected than the other. Parkinson’s tremors happen at rest (when you’re not trying to move the body part) and usually only affect one side of your body unless the disorder has been untreated for a long time.16

An often-cited example of essential tremor is the actress Katharine Hepburn, whose essential tremor affected her head, voice, arms and hands.1 Essential tremor is far more common than Parkinson’s disease, affecting an estimated 7 million Americans.6 The two conditions can be differentiated based on the type of tremor, presence of other Parkinson’s motor symptoms, whether Parkinson’s or essential tremor medications help, and/or a DaTscan.

While essential tremor has historically been believed to cause only tremor and none of the other symptoms that characterize Parkinson’s disease (like slow movements, rigidity, walking changes and balance problems), newer research suggests some people with essential tremor also have motor and non-motor symptoms associated with Parkinson’s.17 More research is needed to determine if essential tremor can evolve into Parkinson’s over a long period of time and if the two conditions are related in some way.

Atypical Parkinsonism

This group of “Parkinsonian” syndromes feature symptoms that look like Parkinson’s disease, especially in the earlier stages of the conditions. However, they each ultimately have their own distinguishing features and causes. Your doctor can tell them apart from Parkinson’s disease based on their lack of response to Parkinson’s medications (specifically carbidopa-levodopa), faster progression, using imaging studies like MRI and PET scans, and unique symptoms that appear over time.

Multiple System Atrophy

Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is a progressive disease that affects the autonomic nervous system — this controls functions like blood pressure, digestion and bladder control — and movement. MSA symptoms include imbalance and falls, tremor, slowness of movement, rigidity, speech issues, trouble with sleep, severe lightheadedness when standing, and bladder control issues. It typically progresses much faster than Parkinson’s disease. MSA often leads to falls and swallowing difficulty.11 Imaging studies can help diagnose multiple system atrophy, in addition to not experiencing long-lasting improvement from the medication carbidopa-levodopa.

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is a degenerative brain disorder that affects balance, walking, coordination, speech and eye movement. Because the symptoms can seem similar to PD, your doctor may think you have PD and instruct you to take PD medications to see if they help. But PSP doesn’t typically respond as well to Parkinson’s medications. PSP can be diagnosed with a neurologic exam and MRI imaging.12 It typically leads to severe disability, and the average time to death is between eight to 10 years from the time symptoms begin.12

Lewy Body Dementia

Lewy body dementia (LBD) is a form of parkinsonism that affects memory, thinking and movement. LBD typically causes fluctuating levels of alertness and visual hallucinations in addition to motor symptoms seen in PD (slowness, stiffness, and tremor). Parkinson’s medications can help motor symptoms but sometimes can worsen visual hallucinations or mental health problems.19 Lewy body dementia can look very similar to Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD). The main way your physician can distinguish the two disorders is using the “one year rule.” In LBD, cognition is typically affected within one year of the onset of motor symptoms, while in PDD cognition usually declines more than one year after the onset of motor symptoms.

Corticobasal Degeneration

Corticobasal degeneration causes degeneration of tissue in different areas of the brain, typically causing drastic changes to one side of the body. This includes severe rigidity, coordination difficulties, uncontrollable muscle contractions, slow movement, and speech issues. If you have corticobasal degeneration, the symptoms progress more rapidly than PD, with the average time from diagnosis to death of eight to 10 years. Since it might seem like Parkinson’s at first, your doctor may initially prescribe Parkinson’s medication to treat the symptoms; however, Parkinson’s medications do not provide lasting benefits. The diagnosis is clinical, meaning it focuses on signs and symptoms rather than tests, and is best made by an experienced movement disorder specialist. Brain imaging can help improve the accuracy of an early diagnosis.2

Related: Find out the lesser-known symptom of parkinsonism that Linda Ronstadt copes with.

Other Challenges of Diagnosing Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease progresses slowly, often with non-motor symptoms appearing months or years before motor symptoms. This can make it challenging for doctors to diagnose you in the early stages, especially since the diagnostic criteria is based mostly on motor symptoms. You may have to wait until your symptoms progress for you and your doctor to confirm your diagnosis.14

Age and gender can be another issue. Since Parkinson’s is associated more with older men, doctors may not think their younger or female patients have Parkinson’s.5 On the other hand, since the disease is associated with aging, your symptoms may be blamed on “getting older.”

Remember that movement disorder specialists are extremely knowledgeable about Parkinson’s disease and can help put the pieces together where other more generalized doctors may not. Never hesitate to fight for the care you deserve.

Related: Here’s what’s important to remember if you were just diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.

Learn more about Parkinson’s: Overview | Symptoms | Treatment | Resources

Sources

- Colino, S. (2015, November 11). The Truth About Essential Tremor: It’s Not Just a Case of Nerves. U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved from https://health.usnews.com/health-news/patient-advice/articles/2015/11/11/the-truth-about-essential-tremor-its-not-just-a-case-of-nerves

- Corticobasal Degeneration. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/corticobasal-degeneration/

- DaTscan. (n.d.). Retrieved August 8, 2019, from https://www.gehealthcare.com/products/nuclear-imaging-agents/datscan

- DaTscan Prices, Coupons & Patient Assistance Programs. (n.d.). Retrieved July 30, 2019, from https://www.drugs.com/price-guide/datscan

- De Leon, M. (2019, April 24). [E-mail interview].

- Essential Tremor. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/essential-tremor/

- Goetz, C. G. (2011). The History of Parkinsons Disease: Early Clinical Descriptions and Neurological Therapies. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, 1(1). doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a008862.

- Luca, C. (2019, April 24). [Telephone interview].

- Marsili, L., Rizzo, G., & Colosimo, C. (2018). Diagnostic Criteria for Parkinson’s Disease: From James Parkinson to the Concept of Prodromal Disease. Frontiers in Neurology,9. doi:10.3389/fneur.2018.00156

- McKeown, M. (2019, May 6). [Telephone interview].

- Multiple System Atrophy Fact Sheet. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/patient-caregiver-education/fact-sheets/multiple-system-atrophy

- Progressive Supranuclear Palsy Fact Sheet. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/Patient-Caregiver-Education/Fact-Sheets/Progressive-Supranuclear-Palsy-Fact-Sheet

- Progressive Supranuclear Palsy: PSP. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.psp.org/iwanttolearn/progressive-supranuclear-palsy/

- Robb, K. (2019, May 5) [E-mail interview].

- Seifert, K. D., & Weiner, J. I. (2013). The impact of DaTscan on the diagnosis and management of movement disorders: A retrospective study. American Journal of Neurodegenerative Disease, 2(1), 29-34.

- Tagliati, M. (2019, April 25). [Telephone interview].

- Tarakad, A., & Jankovic, J. (2018). Essential Tremor and Parkinson’s Disease: Exploring the Relationship. Tremor and Other Hyperkinetic Movements,8. doi:10.7916/D8MD0GVR

- Visualizing Dopaminergic Transporter Status With DaTscan Adds Objective Evidence to Patient Assessment. (n.d.). Retrieved June 6, 2019, from http://us.datscan.com/professional/why-datscan/

- What Is Lewy Body Dementia? (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-lewy-body-dementia

- Yang, L. (2019, May 3). [Telephone interview].