“You must be so devastated,” someone says to me at my nana’s wake.

I nod and tearfully walk away, following a devastated person’s script.

I am 19 and wearing a black dress that fits me weirdly. I fidget and shift in it while I attempt to avoid anyone and everyone. I haven’t yet hit that point where you appreciate condolences. “I’m sorry” feels empty. “She lived a wonderful life” feels cliche. “I’ll think of her every day” feels like a lie. “She’s in a better place now” feels insulting.

I am tired and uncomfortable and cynical as hell and sad.

But I am not devastated.

And that lack of devastation makes me feel like a monster.

***

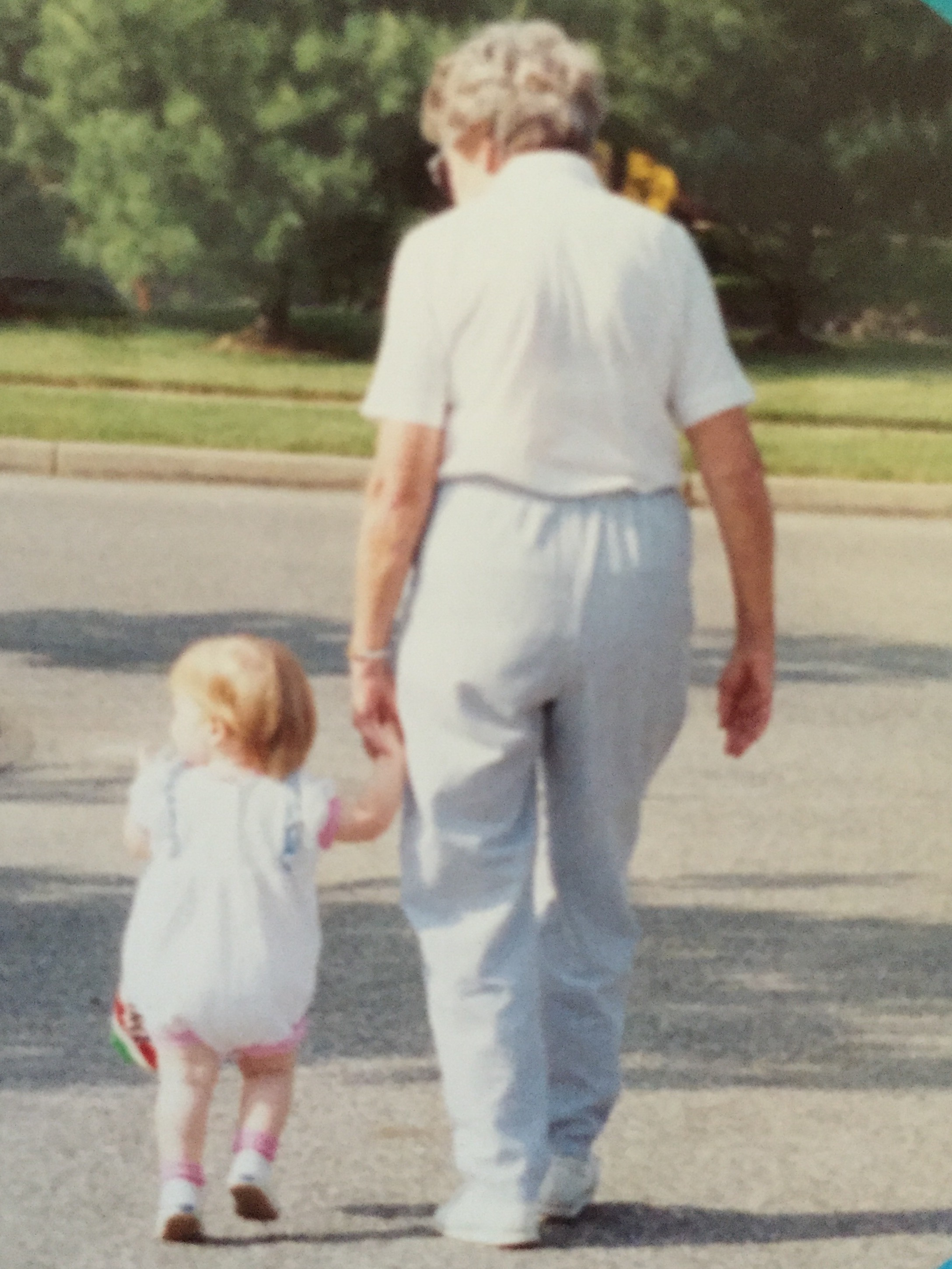

“Kerri, get down from there,” my nana yells, as I defiantly climb the tallest slide in a park in Stuyvesant Town, Manhattan.

I have two problems with this instruction.

1. I am 6 and more than capable of safely using a slide, and “You should know this, Nana, because I am a big kid for crying out loud!”

2. My name is Megan, not Kerri. Kerri is my cousin, the oldest daughter of my mom’s big sister. My nana’s first grandchild.

Nana makes this slip up a lot, but I eventually learn to shrug it off. There are worse things, I decide, than being compared to the favorite grandchild.

***

“Do you want to come to visit Nana with me today?” my mom asks.

I know I have only a few seconds to mull this over. My short answer is no. My slightly longer, honest answer is no, it’s much too painful to see her like this. My out loud answer is OK.

Two years ago, a doctor officially diagnosed my nana with Alzheimer’s disease. At this point, she doesn’t respond when she sees me. She used to respond when she saw my Pop Pop, her husband, but he’s recently passed away. She lives in a nursing home on the Upper East Side, and my mom and aunt rotate in visiting her throughout the week. A series of strokes has reduced her to syllables. We’re not sure what she does and doesn’t process because she can’t tell us. We’re not sure which is worse — when she used to clearly say, “I don’t know who you are,” or now, when we’re left to guess if she recognizes us or not. I say “us” lightly because I have largely removed myself from the situation. I visit when my mom asks me to. I am 17, consumed with myself and convinced this woman is not my nana.

This is not the woman who leaves out butterscotch and Tootsie Rolls when I visit.

This is not the woman who plays UNO with me for hours.

This is not the woman who reminds me to be careful on the slide.

This is not the woman who says, “Love ya, love ya, love ya” at the end of every phone call.

Of course, this is that woman — that exact woman — but I am in a place where I cannot see or understand that. I hear muddled English. I see vacant eyes and bed pans and breathing machines. I spend my time wondering how it’s possible to miss someone who is sitting right beside you. I wake up in cold sweats when I have dreams about her. I cry when I can’t remember where I put my keys.

***

I spend the years after my nana’s death feeling immeasurably guilty. I try to focus on my favorite memories of her — her light laugh, her high-pitched voice, her insurmountable love for her husband, her famous noodles, our summers in Lavallette, N.J. — but I am weighed down by a mix of regret and shame.

What kind of person is not devastated at her grandmother’s funeral? is a question I ask myself often. For a long time I am unable to answer it. What kind of grandchild does not wait on her nana hand-and-foot when she is sick? is a question I avoid but cannot make go away.

***

I can’t name a defining moment where I realized I was torturing myself. It’s been a slow lesson, but I think it comes down to this:

That day at her wake, as I squirmed in my new dress, I was afraid to admit I had already grieved the loss of my nana because I thought that made me sound cruel and ungrateful. The truth is, I’d gone through the devastation when she was first diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and as her symptoms worsened. That devastation was strong and unfamiliar, and at times the only way I knew how to deal with it was by avoiding it. Saying that out loud made me feel like a bad person because it meant I was grieving my nana while she was still alive. I was supposed to be this hopeful, patient, thank-God-she’s-still-here grandchild. Not devastated and angry. What if, by admitting I was grieving a living person, I had been belittling my nana’s presence?

***

The five stages of grief are simplistic. Denial. Anger. Bargaining. Depression. Acceptance. Of course, this model is meant to be simplistic, but I think sometimes we run the risk of forgetting that we’re allowed to feel more.

Because we do — we feel so much more than that. We have in-between feelings that don’t have names. They knot and twist and build up inside us, clogging our arteries and pores. They’re foreign and confusing, terrifying and sometimes even beautiful. We cannot identify them with a dictionary or an ultrasound.

Alzheimer’s is an intricate mess of in-between feelings. You’re lost between patience and anger. You’re torn between dedication and what feels like — but isn’t — abandonment. You’re caught between defeat and hope. You begin to mourn the life of someone who is still alive and are immediately met with a heavy guilt. “People are actually dealing with death,” you tell yourself. “You should be grateful she is here.”

But grief is incomparable. I think we have to grieve in our own way, respect the way others grieve and not be locked into a specific way of grieving. We cannot feel guilty for our form of grief. We can learn from how we grieve, but we can’t shame ourselves for doing it the “wrong” or “inappropriate” way.

***

I was not an adventurous child.

When my nana tells me to get down from the slide, I do. I walk over to her on the bench, grumpy and prepared for battle.

“Nana, why don’t you ever let me go down the slide?” I demand. “I’m not going to get hurt.”

“I worry, you know that,” she says. “I just love you too much. I love ya, love ya, love ya.”

It’s a phrase we’ve since adopted as a family. It’s how we say goodbye to each other — on the phone, in person, via text message. It’s muscle memory at this point. I’ve always liked it because it’s become our own special way to say goodbye, I love you, see you later.

I don’t remember the last day I saw my nana alive, but I know this. Before I left I said, “Love ya, love ya, love ya.” And through the years of guilt and regret and disappointment in myself, I’ve realized that is enough.

I said goodbye in my own way, and that is all anyone can do.

Related: When My Pop Pop Taught Me How to Face Alzheimer’s Disease