Editor’s note: If you experience suicidal thoughts or have lost someone to suicide, the following post could be potentially triggering. You can contact the Crisis Text Line by texting “START” to 741-741

“Half of the time we’re gone but we don’t know where, and we don’t know where.” — “The Only Living Boy in New York,” Simon and Garfunkel

Story goes that Andy Edison killed himself early one April morning in ’78, just shy of my father’s 14th birthday.

• What is Bipolar disorder?

Dad wrote that he remembered Edison for his heavy gin breath, unfocused eyes and penchant for leaving the TV on 24/7. He had a house overrun by plants, an unexploded shell left over from his days fighting in World War I and a wife who was dead. So my grandmother pitied him.

Once every few days, Dad or his sister would make the walk, weaving under the trees separating the houses, to drop off some leftovers, books, whatever his mother left on the table for that “poor old man.” On Christmas, they’d sit across the table from their surly neighbor, embodying that acutely awkward feeling you get when you’re confronted with another person’s sustained pain. (You’re sure there’s something you’re supposed to do or say, but you can’t ever seem to tap into the right script or choreography.)

Despite the dazed almost-expressions shared in those visits, he was obviously grateful for it all. Sometimes you just need to know that someone, anyone still cares.

Before Edison went, he gave my grandmother a little over $2,000. It was a check she didn’t want to cash, but three months owed-rent, several part-time jobs cleaning houses and a husband who fancied himself a vagabond intellectual left her little room for pride.

The check cleared just hours before he pulled the trigger. And even though she wasn’t the one to clean the warped halo of blood off the walls, the story left a strange taste in his mouth. Dad called the money “a finders fee,” which is funny until you remember that it isn’t.

Dad wrote that he’d thought about Edison a lot since then, especially after he got arrested and after he was diagnosed, when he picked up the bottle and put it down again every couple of years and when he finally knew what it took for a man to get there.

* * *

The day before the story hit the papers, we made the drive to Riverdale where my older sister was a freshman in college. The September air hadn’t started to take on the bite of fall but, the way I remember it, it should’ve been winter. We picked her up at her dorm, heading toward Broadway without really knowing what we were looking for.

“You might hear some talk in the next few days,” he took a pause and the engine hummed underneath it. “But I’d rather you hear it from me.”

He left his former job earlier that summer and we were just finding out why. He said a lot in that hour, but he never could get to the part I wanted to hear: that this was a big misunderstanding.

“I’ve always been crazy. When I’m good, I’m good, you know? But, when I’m not…” he started. “It’s not that I don’t know right from wrong; it’s that I just don’t care.”

Again, a pause and humming. I thought of the road trips where he’d drive too fast and charm his way out of traffic tickets; the late summer days where he couldn’t bear to watch the leaves change (or get out of bed); how he turned periods of break-neck energy and enthusiasm into walls and pillars overnight; how he picked fights and apologized within minutes but never seemed to care whether he’d hurt someone.

The bipolar disorder made a lot of sense. Although the way he explained it was purposely simplistic and self-deprecating enough to engineer the least panicked reactions from the three of us.

My older sister held her hands in her lap, fist making crescent-shaped marks in her palm as she listened. I flicked my fingers over the child locks on the backseat doors. Up down, up down, up down.

* * *

He used to run track. He still holds records at North Salem High School and a plaque sits at an awkward angle just to the left of the attendance office at the school. I remember he showed me it once. It’s there among a mass of other haphazardly-placed awards from the kids who grew up and had families and the ones who didn’t.

He used to run track. He still holds records at North Salem High School and a plaque sits at an awkward angle just to the left of the attendance office at the school. I remember he showed me it once. It’s there among a mass of other haphazardly-placed awards from the kids who grew up and had families and the ones who didn’t.

Some days I try to picture him running: A face without frown lines, muscles relaxing with legs that seem longer and less pained as his feet hit the pavement. Maybe there was something rhythmic and peaceful about the practice back then. I can’t really see it, to be honest.

Dad was a sprinter. It suits him when I really think about it: that rush of energy and adrenaline. There’s no need for economy in step or effort; use it while it’s here. Recover later, if you can. No shame in burning out, as long as you’re ready by your next race.

That always made sense: On good days, there were good races and he hurt like hell after. But, he’d always prefer to ice a win.

* * *

A few months after the arrest, Dad started to work odd jobs at construction sites in the city. He was trying to bring some money in by relying on favors from the old friends who’d still pick up the phone.

He always caught the last train home, getting off at Valhalla or White Plains, somewhere with cheaper parking.

He’d spend his nights tapping away at empty word docs with that posture that’s so intimately familiar to me now, writing up the chapters and stories of his life — I know these were words that he absolutely never meant for me to find. I love them anyway.

He was trying reclaim that bit of himself: He wanted to remember what it was like to be the young boy who walked New York City streets with father on their way to work, to be the heartsick teenager who was one half of “the longest running mutual crush, lubricated by coffee.” He was looking for what it felt like before he “embraced the crazy.”

He still doesn’t know I read those words or that I squirreled them away, keeping them close for all these years to reread on nights when the house gets too quiet. It’s like some private reminder that there’s something — other than our eyes and our tempers — that the two of us still share.

“I’m too mean to die,” he wrote, quoting a line his grandfather liked to use, “at least when I’m manic. I hope I’m too sad to die when I’m not.”

The worst nights, he wrote, he’d watch streetlights make shadows over the train tracks, the weight of everything tugging at his bones. He wondered what that final step would feel like (I’m thinking that maybe it weighed as much as that 8-inch by two-inch shell.) But, make no mistake, I hated this part of the story.

“You know, Valhalla is the only place in the state where the dead outnumber the living.” I heard that at my great grandpa’s funeral. I guess it stuck.

A few months later, after he finally stopped taking the goddamn train every day, he’d managed to find another way to slowly, slowly rebuild. Every day since I’ve been thankful for that.

I don’t know if my dad is ever going to pick up his story again, if he’ll ever try to look at it with new eyes. I haven’t managed to fully make sense of the last six years myself.

But I’ve gotten good at telling the story in a way that makes everyone seem a bit nobler, a bit smarter and a bit nicer than we really were. I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to unpack the ways our family has been touched, broken and rebuilt, but I’ve gotten used to explaining the parts of our lives that are still inching back on track.

“I got a win today,” he still says when finally, finally something goes right. Coming in after a long day, breath heavy with his beloved bulldog at his heels. “We got a win.”

There’s a part of the story that I don’t get to tell all that often, about what comes after the fall, after the pain, when the world finally starts to look normal again.

It’s not quite a happy ending or some kind of temporary calm. It’s the part of the story I’m not all that good at telling just yet, but it’s the promise that the next page is coming.

This post originally appeared on Medium.

If you or someone you know needs help, visit our suicide prevention resources page.

If you need support right now, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or text “START” to 741-741.

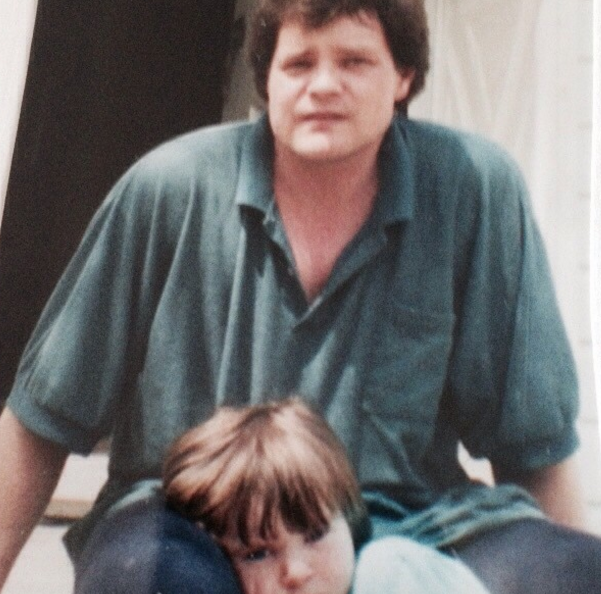

Images courtesy of Katherine Speller