What Recovery and Remission Mean When You Have Borderline Personality Disorder

Recently, a Facebook friend posted in one the many borderline personality disorder groups I belong to that his psychologist told him that he no longer meets criteria for BPD. On a different BPD page someone asked the question if anyone had ever been told they no longer have BPD. I lost count of the number of people who say they had. There were even mentions of being cured like a person is cured from a disease, or receiving an “undiagnosis” (usually by a psychologist, interestingly). And confusingly there seemed to be different definitions of recovery and remission.

My response to all of this was not joy and inspiration, but a kind of defiance and disbelief. Of course I want everyone with BPD to be as free from as many of our brutal symptoms as possible and understand people don’t want to be defined by our still stigmatized disorder. While I have known for years that BPD has high remission rates, honestly I was close to doubting their claims. I posted in the groups that healed or cured would never be true for me. I conceded that there is undoubtedly remission from meeting the nine diagnostic criteria, but as our disorder is arguably part of our personality to some extent, can we ever be entirely rid of it? It may no longer impair functioning in our life, but don’t we still have personality characteristics that could swiftly remit if we’re not mindful, or if tragedy or broken relationships strike us? And isn’t this thinking the ultimate dichotomous bind of BPD black and white or all or nothing thinking? We are forced to see ourselves as sick or recovered and nothing in between?

Am I running from my own recovery?

Now a few weeks later I question if I have fallen victim to a kind of mental illness seduction; believing that old cliche that we are taught to fight, I am my illness. Certainly every time I write this past year I essentially write about my BPD. Could I be running from my own undiagnosis? Do I even meet clinical criteria for BPD anymore? I was misdiagnosed or rather underdiagnosed with solely major depressive disorder for most of my adult life, not arriving at a BPD diagnosis until I was 37. Am I scared someone will suddenly take it away from me like a favorite child, or the child you unconditionally love who nevertheless drives you to distraction?

I needed answers so decided to start with whether I still meet the clinical criteria for BPD, and tried to imagine what recovery or remission or even cure would look like for me, and crucially whether it is possible.

Am I still borderline, according to the DSM 5 and dialectical behavior therapy?

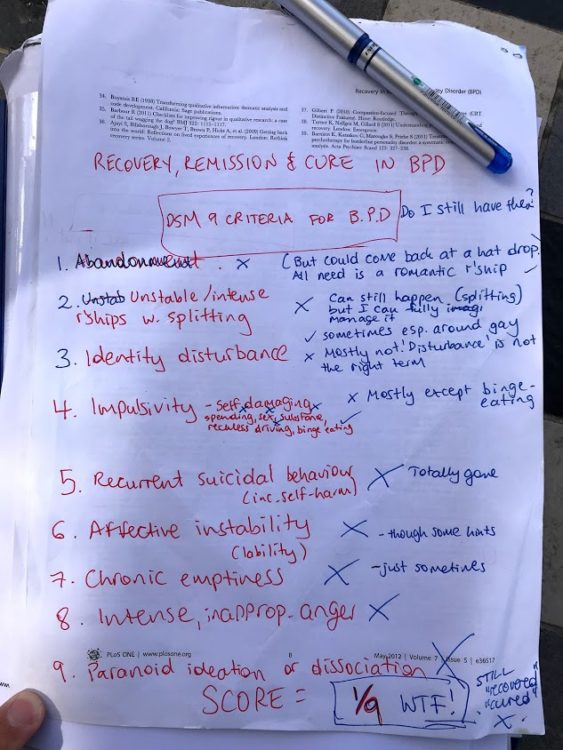

I sat down at a local cafe last Thursday afternoon and I went through the diagnostic criteria one by one, which looked like this:

- Abandonment — No

Could come back at a hat drop. All I need is a romantic relationship or even just dating. - Unstable/intense relationships with splitting — No

Can still happen. Felt jealous when a friend recently had to hang up the phone to meet his girlfriend. Last worst split on a friend was in January. But I can manage. - Identity Disturbance — Yes

Mostly not. Some disturbance but maybe a free-floating feeling around who I am at times. Still, unpleasant enough a feeling to tick yes. - Self-damaging Impulsivity — Yes

Only binge eating and one other compulsive behavior not on this list. - Recurrent suicidal behavior including self-harm — No

No suicidality for over three years now, but last self-harm was before my last hospital stay in October 2019. - Affective Instability — No

Mostly not but there are still some days when my emotions change rapidly. - Chronic Emptiness — Yes

Emptiness yes. Especially intense at night but not chronic. Maybe half a tick. - Intense, inappropriate anger — No

Almost nothing but then I yelled at a family member last week. - Paranoid ideation or dissociation — No

Not for four years now.

The answer was a resounding no! I self-scored a very low 2.5/9 (scaled up from the below photo). Not even close to the requisite 5. WTF!

Yet, I didn’t jump for joy. It was confronting. I didn’t feel cured, or recovered or even in remission. To me, there is more to recovery than just a set of criteria. I thought of my year in Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) and wondered; was I now mindful, emotionally regulated, tolerant of my distress and interpersonally effective? I have to say mostly yes. 4/4!

That was the clinical gauge and the therapeutic behavioral gauge, but I wanted my own “lived experience” gauge. Quickly (still at the cafe) I came up with my own recovery measure or goals:

“It used to be to go back to how I was before [I got sick], but now I feel that is not possible or even desired (as I am a new person now). So? — less pain, more calm, more confidence, more hope, being able to see myself and my relationships realistically. More love (though even in the most crushing darkness it’s been there), even a relationship. Something to look forward to, strive towards and get out of bed for. To fulfill my creative and vocational gifts and goals without activating my devastating unrelenting standards. A radical acceptance of myself, my relationships, the world and its profound brokenness and suffering both now and in the past and into the future.”

From that long list I can only see a relationship missing and creative gifts and goals not yet fully being met, though writing for The Mighty is certainly helping, as is a rewarding new online job. In the end this is an opportunity to practice self-compassion over unrelenting standards.

It is clear that I am doing well even during a pandemic, but I still don’t want to call myself recovered, no matter how high I score. It was only 10 months ago I was in hospital where I would have met much of the criteria for BPD and felt so far from my personal goals.

To help me try and resolve these questions, I turned to academic studies and clinical trials. A note that I will now move from a personal to a more academic voice to report this recovery data.

Clinical trials literature around BPD recovery, remission and recurrence:

In the wake of my diagnosis four years ago, I researched as much as I could and along with the adjectives “chronic” and “severe” next to the disorder. I also came across a number of clinical trials about the longitudinal course of my disorder. I remember the hope they gave me even in my desolation, the studies all talked about very high recovery or remission rates long term and its good prognosis among other personality disorders. Discovering this data, along with a few articles from The Mighty, really made me feel like I was going to be OK, if I could just hold on.

With all my current swirling questions around my own borderline remission I decided to return to these studies but in much more depth and breadth. I found one book and eight studies of clinical trials and literature reviews from Australia, the UK, Canada and the United States and found many consistencies in their findings.

Firstly around the definition of BPD recovery, a joint study from Australia and the UK argued that; “The concept of recovery… is not well defined” and upheld the clinical definition of symptom reduction but emphasizes that “consumers advocate for a holistic approach” (Ng et al., 2019).

This holistic approach seems to have slightly different focuses from study to study from “self acceptance, gaining control over emotions, improving relationships, employment” (Katsakou et al, 2012) to “reconciliation of self…fostered through interpersonal relationships and integration within the community” (Ng et al., 2019) and “a good, full-time vocational or educational functioning and at least one stable and supportive relationship with a friend or a partner” (Biskin, 2015).

However, not all study participants even liked the word recovery, as one in a UK study argues; “I think recovery is a very difficult word particularly with mental illnesses … I don’t want to say I’ve recovered because I don’t want to give myself an opportunity to relapse” (participant nine).

Overall, many of the studies stressed that more “consumer” perspectives on recovery were needed in future studies.

The word remission seemed to have a clearer, more consistent definition across the literature usually defined alongside its seeming opposite recurrence. Remission is defined by another study as “no longer meeting the specified criteria for BPD,” while recurrence is “meeting diagnostic criteria following a period of achieving remission.”

In terms of actual remission results Biskin made a literature review, especially of the two most prominent BPD longitudinal studies at the time of publication, and the remission and recurrence data are overwhelmingly, even shocking in their consistency given the stigma that still shrouds our illness. While Biskin acknowledges that “patients with BPD do suffer intensely..their prognosis is often better than expected and the outcomes are further improved with appropriate treatment.” The specific data from the two studies Biskin cites, the McLean Study of Adult Development (MSAD) and the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Studies (CLPS), clearly show that “most patients with BPD improve over time.”

CLPS found that one out of four of patients experience remission during a two year period, and after 10 years 85 percent achieve remission for 12 months or longer. MSAD extended this even further to 16 years where 99 percent of patients have at least a two year remission and 78 percent have a remission lasting eight years.

Even more, Biskin cites another study that followed up patients after 27 years finding 92 percent no longer met BPD criteria. As for recurrence the MSAD rates decreased the longer the remission lasted; 36 percent of patients experienced a recurrence if their remission lasted only two years, but this declined to 10 percent if their remission lasted eight years.

Interestingly, the impulsive and acute symptoms (such as self-harm, suicidality, impulsive behaviors) were the fastest to remit but the temperamental and affective ones much slower (such as emptiness, anger, labile emotions).

A 2014 study found 60 percent of borderline patients studied achieved a two year recovery over 16 years of follow-up. Here, it is important to acknowledge that some studies were not as optimistic in recovery outcomes, with the same author arguing in 2018 that, “it is more difficult for borderline patients to achieve recovery [defined as symptomatic remission & good social and full-time vocational functioning] than to achieve symptomatic remission.” While this may be discouraging, it perhaps supports my gut reaction that “recovered” is not a state so easy for us to attain or maintain. Still, the studies give many recovery predictors with some consistencies including prior vocational functioning, engagement in the treatment services, meaningful relationships and activities, among others.

In the end, the lower recovery rates do not detract from the extraordinary remission rates of a disorder that many people and still too many doctors classify as chronic and assign it to the untreatable basket. Clearly, it is treatable.

Where does this leave me? Recovered, remitted yet still identifying?

Overwhelmingly, the BPD prognosis is good. I first read this soon after I was diagnosed and it gave me hope. It still gives me hope now, and I imagine many of my fellow strugglers too. But I will not budge from my diagnosis identification. As I argued in a previous article it fuels my superpower, and yes it can still be a curse, but overall it has helped me understand myself and my past in a way little else had before. It has made me unique, it has made me strong, and it has made me love people and feel things with a fierce and profound intensity. I don’t want to lose the color in my character.

Of course there are other crucial contributors to my identity outside my illness and I felt rebuked by the MSAD’s conclusion that “mood disorders are illnesses that people have and not dimensions of who they are.” Point taken. But don’t take this identity away from me when it was so hard fought.

Rather than stigma, I see great gifts.

Just an hour ago while getting a massage, my masseur explained to me that he broke his body when he was in his 30s working manual jobs and essentially taught himself to relearn the use of his arms and legs by learning all about the human body (and how he became a masseur.) With no knowledge of this article I was writing, or my mental illness story, he said; “I am better, but not healed. I’ve still got problems.”

My sentiment exactly.

Reference List

1. Recovery in Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD): A Qualitative Study of Service Users’ Perspectives (2012) Christina Katsakou, Stamatina Marougka, Kirsten Barnicot, Mark Savill, Hayley White, Kate Lockwood, Stefan Priebe.

2. Recovery from Borderline Personality Disorder: A Systematic Review of the Perspectives of Consumers, Clinicians, Family and Carers (2016) Fiona Y Y Ng , Marianne E Bourke , Brin F S Grenyer.

3 . The lived experience of recovery in borderline personality disorder: a qualitative study (2019) Fiona Y. Y. Ng, Michelle L. Townsend, Caitlin E. Miller, Mahlie Jewell & Brin F. S. Grenyer.

4. The Lifetime Course of Borderline Personality Disorder (2015). Robert S Biskin.

5. The McLean Study of Adult Development overview and implications of the first six years of prospective follow-up (2005).Mary C Zanarini , Frances R Frankenburg, John Hennen, D Bradford Reich, Kenneth R Silk.

6. Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Studies (2005). Andrew E Skodol , John G Gunderson, M Tracie Shea, Thomas H McGlashan, Leslie C Morey, Charles A Sanislow, Donna S Bender, Carlos M Grilo, Mary C Zanarini, Shirley Yen, Maria E Pagano, Robert L Stout.

7. Prediction of time‐to‐attainment of recovery for borderline patients followed prospectively for 16 years (2014) Mary C. Zanarini, Frances R. Frankenburg, D. Bradford Reich, Michelle M. Wedig, Lindsey C. Conkey, Garrett M. Fitzmaurice.

8. A 27-year follow-up of patients with borderline personality disorder (2001). Joel Paris, Hallie Zweig-Frank.

9. In the Fullness of Time: Recovery from Borderline Personality Disorder (2018). Mary Zanarini. Oxford University Press.

Getty image by solarseven