Standing in a room heavy with suffering is its own kind of awkward. It is not that different from the awkwardness of a low-stakes work presentation. What do I do with my hands? Where do I look? Am I speaking too fast? Too slow?

Sitting in the neuro ICU with my sister, the awkwardness is familiar, only every muscle is tense to keep me composed as Mom cries uncontrollably, wondering how something so cruel and unfair can happen.

My little sister has come back from the brink many times. Though with each near death, it feels like something precious is taken from her as payment to stay. Her memory, her balance, her eyesight, her hearing, her bowels, the ability to enjoy food, her movement, to satiate her thirst, to breathe, to speak… she’s stubborn though. She’s not going anywhere until she damn well pleases.

I keep a mental list of rules on how to appear for all possible interactions:

1. Don’t look too hard at the brutality of the surgical scars, the tubes and needles, the tiny bruised and emaciated body, while sitting at her bedside.

2. Don’t look worried when engaging with her (smile!).

3. Don’t focus on the simultaneously sickly yet sterile smell of the room.

4. Don’t cry when another person is crying so they can be allowed to fully grieve with the assurance it is OK for them to let it all out and be vulnerable in the space.

5. Look thoughtful and unquestioningly stoic when the doctor is giving their assessment (no matter how cold, condescending or insensitive they may be).

6. Be as kind as possible to the nurses and support staff (they do not get nearly enough credit for what they do).

7. When it’s just the two of us, I can quietly sing lullabies, that is until I feel I might lose composure and break my rules.

Pulled back and forth between consciousness, and slowly rusting from the inside out due to a tiny bleed in her brain, my sister is exhausted. Intubated, she can hardly speak, her condition (superficial siderosis as a complication of a brain tumor) also means she can barely hear. Some days are better than others. She is desperately uncomfortable. Unable to eat solid foods, one of the last small comforts she was able to cherish, gone. I sit and watch uselessly as nurses and caregivers throw their hands up in frustration, unable to communicate. Begging us to get her to comply. Her red in the face with anger. At least they try. The doctors don’t understand the point of it.

“I would never want to live like this. Would you?”

“This is not the kind of thing you bounce back from.”

“She’s not there anymore.”

“It’s not like she’s a rocket scientist.”

We nod to let them know we’re taking it all in. She’s often aware. She’s just trapped. Able to muster short answers now and then. They don’t see her eyes light up when we show her pictures of animals. They don’t feel her hand tightly gripping my mom’s as she tells her she loves her. They don’t know what the slight sneer on her face means as we tease her brothers. They weren’t in the room when a massive, fluffy bernedoodle sporting ridiculously long eyelashes jumped up onto her bedside while she was comatose, causing her to open her eyes and reach out to pet him.

My sister was diagnosed with a pilocytic astrocytoma midbrain when she was 10. She collapsed as we walked to the library one summer. The kids all sat hushed, adults rushing around us, catching pieces of broken sentences.

“Probably just an ear infection.”

“The size of a lemon.”

“Cancer?”

“We can’t say that for sure.”

We got to eat McDonalds, a rare treat, but us kids just sat quietly in the dark van listening to crinkling wrappers, struggling to swallow chunks of tasteless cheeseburger while we drove home without our sister.

As I sit, my skin melting into the blue upholstered hospital chair, I recall how depressed I used to get when I lost my voice even for a few days. This would be unbearable! There is a pad and whiteboard on the table. Mom uses an EXPO marker to tell my sister she has to take her medicine, what day it is. Short, essential information.

The next time she refuses to take her medicine and the nurse leaves in frustration, I grab the whiteboard and ask “Why?”

She looks at me surprised to actually be engaged in conversation.

“I don’t trust you!” She struggles to blurt out.

“Why don’t you trust us?”

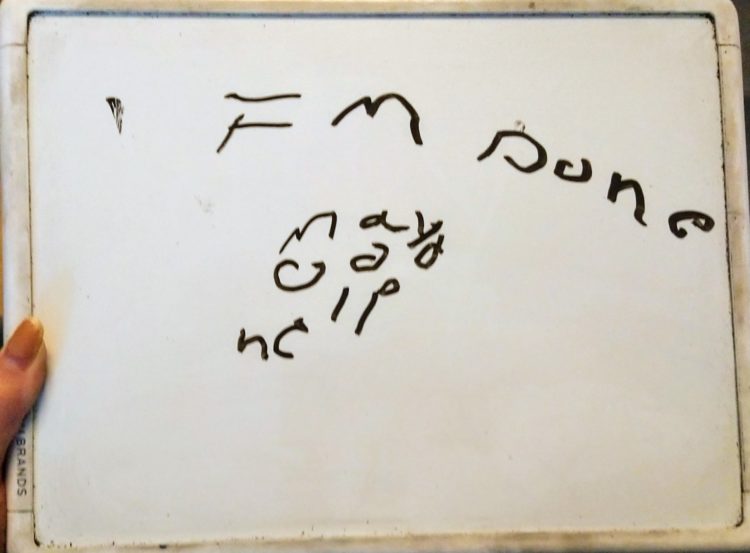

Her energy used on the full sentence, she motions for me to bring her the board. She feebly writes “IM Done” along with three more words I cannot decipher, she closes her eyes, lips clenched.

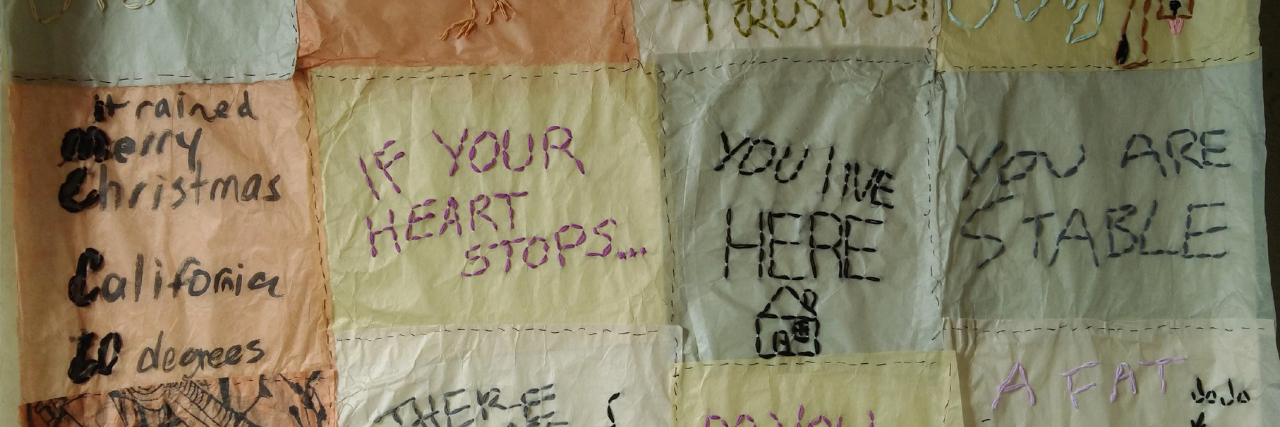

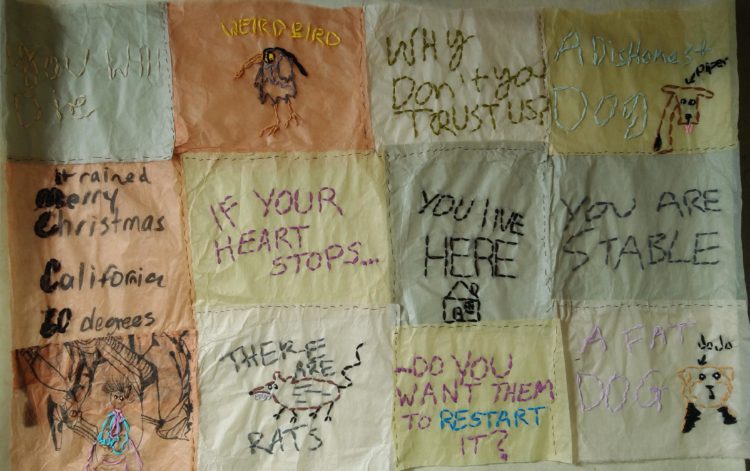

From then on we replaced the awkward silence with whiteboard conversations. Sometimes one-sided, oftentimes just pictures of cartoon dogs, things I had seen that day. A picture really was worth a thousand words when it became the most efficient way to tell her she had a new nephew. Two familiar caricatures holding a generic baby. We even play successful games of hangman.

Weeks later, I scramble for my pen and sketch pad in the ER. Trying to think of the most efficient way to ask a dark question.

“If your heart stops… do you want them to restart it?”

A weak nod, “Yes.”

I return to my art studio across the country and pull piles of loose conversations smuggled from my visits with her. I need to make them into something permanent and substantial. I need a task to obfuscate my helplessness. How do you grieve for the living?

I painstakingly pull a needle and thread through delicate tissue paper embroidering our conversations into soft, blushing transparent red paper. As I finish struggling with “IM Done,” I trace the other three words and finally decipher:

may

god

help.

Original photo by author