A month ago, my husband and I were having dinner at Table 87, our favorite Brooklyn pizza joint. I held my babbling 5-month-old baby girl on my lap, kissing her between sips of wine. I was fresh off a whirlwind business trip that had gone exceedingly well. My husband was excited about a potential job opportunity in San Francisco that would allow us to live closer to family.

As I nibbled my pizza and looked at my family, I thought, “My life is perfect.”

And then, one night, I was lying in bed marveling at the strangeness of my postpartum body — my breasts in particular — when I found a lump. I thought by not breastfeeding my boobs would stay intact, but they still felt like flabby, deflated balloons — and my left balloon had a weird hard bump about the size of my pinky knuckle. I wondered if it was my rib I was feeling, or some other totally normal body part once hidden by ample boob fat. I checked to see if the right side contained a symmetrically similar oddity, but there was nothing.

I made a mental note to tell my OB/GYN the next time I saw her, which would be in about two months. I went back to living my life, but fell asleep each night feeling that little lump, just checking if it was still there, trying to quell the bubbling panic because it was, after all, a lump.

You might be wondering why I was willing to wait so long to get checked out. Well, while I cared about my body, I never routinely subscribed to the whole self-exam thing. When my doctor would palpate my breasts and ask if I self examined, I would giggle and make crude jokes.

Recently, I remember reading a piece about breast cancer in “The Atlantic” and smugly thinking to myself, “Thank goodness I don’t have to worry about this.” Lymphoma was the cancer du jour in my family, and I had like no boobs to begin with.

Breast cancer was definitely not gonna catch this bitch.

I told my husband and some friends about the lump. Their reactions hovered in the “You’re a hypochondriac” and “You’re young” and “You just had a baby” and “You’re fine” and eye-rolling ecosphere. They all paid lip service to getting it checked out, but no one seemed to have any real urgency about it. And while I was weirded out by my little lumpety lump, I figured it was a residual pregnancy thing since so many other bizarre things had happened to my body in its post-baby-making days.

My OB/GYN appointment was supposed to be about the IUD. Hormones aren’t my friends, so the copper IUD seemed like the best birth control option. But I’d been reading about IUDs and had decided the pull and pray best suited my style and would allow me to circumvent all contraceptives and their less-than-ideal side effects.

I could have canceled my appointment since there really was nothing to talk about, but I decided I should probably have this little lump examined. We spent the first half of the appointment talking about my birth control choice and then discussing my adorable baby. And then, just as the doctor was leaving, I remembered the lump.

“I have this other thing. Can you just feel me up and see what it is?”

My doctor did a perfunctory examination. I remember her using words like “hard mass” and “movable” and “small” and saying something like, “It’s definitely nothing to be worried about, but I can write you a referral for an ultrasound.”

I took the referral, and a week later, I was half naked on a table while a technician did an ultrasound. Within minutes she left the room and the radiologist entered, firing questions at me about my history, my age, my lifestyle. He ordered a mammogram, and moments later, I was enduring one of the most painful and demeaning procedures I’d ever experienced.

As the machine clamped down, ferociously pinching my itty-bitty boobs, I started to sob. The technician asked if I had family with me. I said no. Why would I? I thought I was here for an ultrasound that would simply confirm what everyone else had told me — “This was no big deal.”

The radiologist brought me into his office and showed me the image from the mammogram. “You have a nodule with calcifications,” he said. Frustrated, I asked, “Well what the fuck does that mean?” He said it could mean a lot of things, but they would need to do a biopsy to be certain.

First thing Monday, I was back for the biopsy. The radiologist who conducted the biopsy said, “It’s unfortunate you’re so young,” when she walked into the room and started looking at my images. I’m certain she didn’t mean to say that out loud, but it put me on edge. I cried the entire time. Not because of the discomfort or the sharp pricks of the needle, but because I knew something was wrong by the way everyone was acting, and no one was giving me any information.

Upon completion of the biopsy, the doctor looked at me and said, “We will call you tomorrow. I want you to know that whatever we find, it is treatable.” At that point, I lost it. “What the hell is going on here?” She made some incoherent comments in doctor speak and I left the office in a numb stupor.

Waiting for the biopsy results, I willed myself not to let my head to go to all the worst places. I reminded myself I am young. Breast cancer doesn’t run in my family. I just had a baby. I am a yoga monster. I am strong. I eat well. I take good care of myself. I’m a good person. I drink tons of water. I’ve never done drugs. I lead a mostly boring life.

But none of that mattered because at the end of the day, cancer doesn’t give a fuck. And it got me.

When I got the news I was completely devastated.

And shocked.

And sick to my stomach.

And outraged.

And confused.

And sad. So sad.

“I can’t believe this is happening,” was all I could think. Over and over.

Though I could feel myself slipping into a black hole of depression, I forced myself into warrior mode. I immediately had an ultrasound and mammogram of the right breast. I had an MRI to get better imaging of both breasts and my lymph nodes. I scheduled an appointment with the most badass breast surgeon I could find. I Googled the hell out of my pathology report so I could understand everything there was to know about my cancer. I read about lumpectomies and radiation therapy and hormone therapy and chemotherapy and mastectomies. I prepared lists of questions.

Within one week of my diagnosis, I had assembled my cancer-fighting dream team — all of whom are whip smart, renowned in their fields, beautiful, badass women. I had a breast surgeon, a plastic surgeon, a psychiatrist, a therapist and an oncologist all working together to make sure I was going to fuck cancer hard.

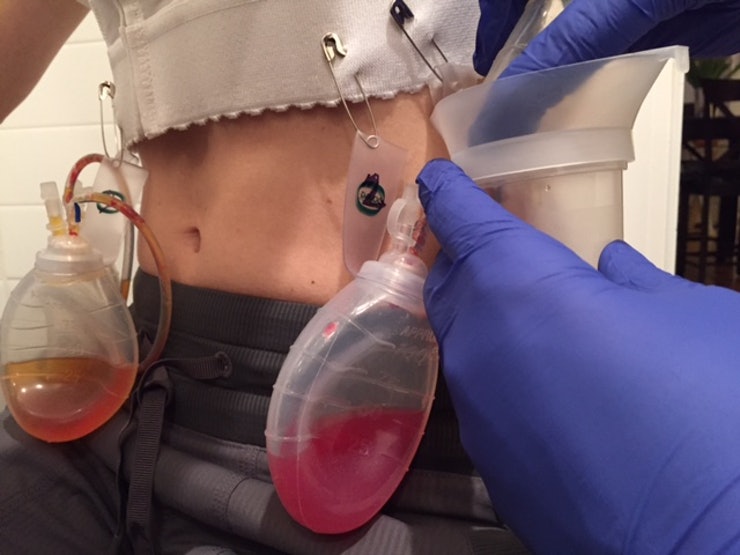

Last week I took the first step towards my recovery — a double mastectomy. During surgery, they biopsied the lymph nodes and they looked good. Everyone high-fived. They don’t even know me, really, and they high-fived.

These are the people taking care of me. I am so blessed.

I will know more about my cancer when I get the pathology report and meet with my oncologist in a few days, but I have some peace right now knowing the lump is out.

And here’s something else that gives me comfort during this otherwise sad, difficult time: I caught this early. I found the lump. I took action in assembling my team and advocating for my needs. I saved my life.

But I have a long way to go. As I write this today, I still do not know what lies ahead in terms of my treatment. I am sad and scared and anxious. And I am grieving. I’m grieving the loss of my breasts and my nipples. I’m grieving the loss of my carefree invincibility.

But I’m also angry as hell.

I’m angry I never knew how serious breast cancer is and someone my age and without any family history could be susceptible.

I’m angry it’s become kitschy to wear pink and talk about saving boobies, but to not really understand this disease and its implications for young women.

I’m angry thinking had I been nonchalant, this would be a completely different story.

And that anger is what fuels me to speak out about this, to ensure as many women as possible learn from my story. Because health means knowing your body so damn well, when something feels just a little bit off, you notice it right away.

It means not ignoring the things that scare you and insisting upon getting ultrasounds, mammograms, MRIs and/or biopsies right away so you can be 100 percent certain it really is “no big deal.”

It might mean doing genetic testing. And it certainly means seeking out the best possible team of professionals who will take the best possible care of you — and settling for nothing less.

Cancer is random and fucked up and awful.

There is so much about this disease one cannot control. But the things we can control, we must own — like a boss.

This post was originally published on Bustle.