I love the work of artist Johan Deckmann. He uses books and their titles to convey universally relatable truths about life. His images are powerful and thought-provoking. They directly inspired me to create my own book series on myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), more commonly known as chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), to help raise awareness.

The “ME Anthology Series” helped me express a lot of the heavy feelings that come with living with this disease —whether it be grief, the trauma of being disbelieved, the experience of not having access to ME-literate doctors, and the fact that no treatments exist for a disease that is so disabling even in it’s mildest forms. It makes me have a lot of fear surrounding my future. With this series, I wanted to communicate a sense of urgency for change that permeates our entire community. We are all so sick, and the status quo is keeping us that way.

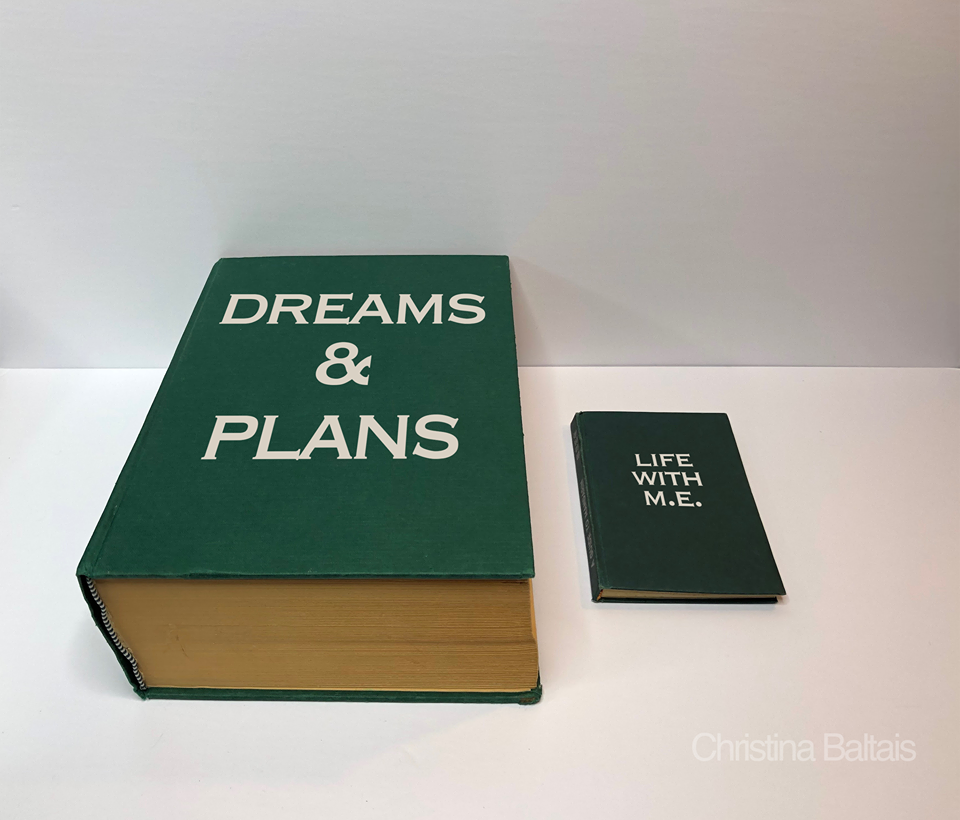

This image conveys the experience of how ME forcibly shrinks the walls of your life down. The dreams and plans you once had become skinny, abridged and adapted versions of what remains. It’s a catastrophic downsizing of sorts, with omnipresent grief. This is by far my greatest struggle with ME, because chapters and chapters have been removed from what I thought my life would be like.

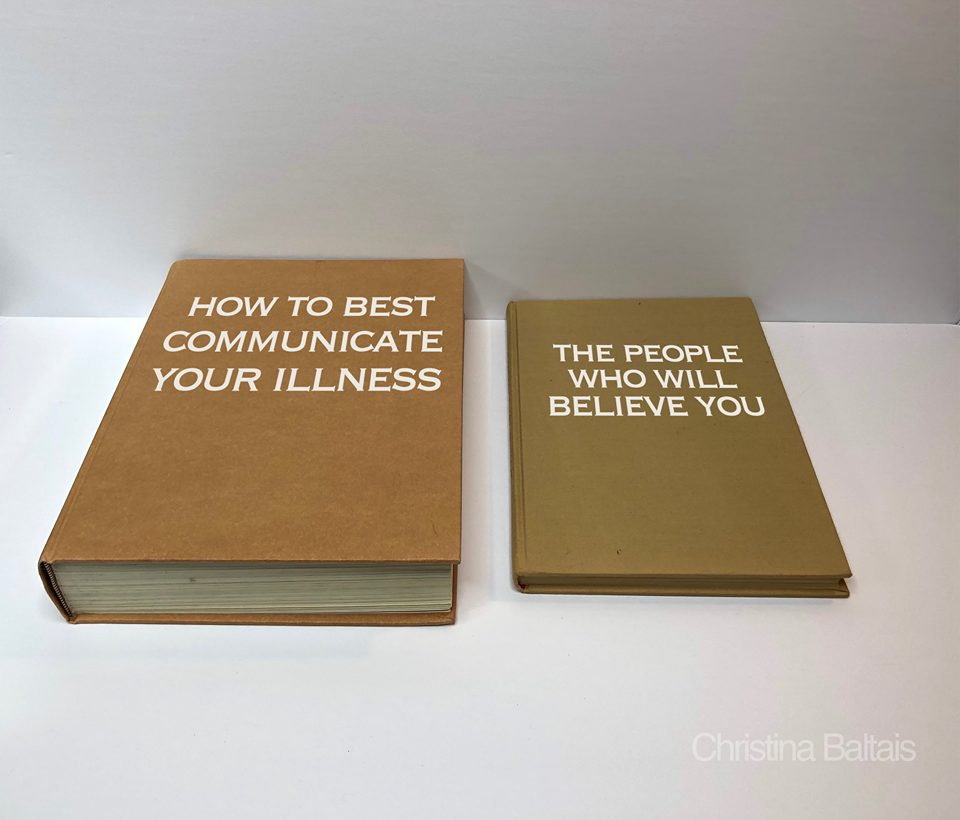

This image represents the likelihood of being disbelieved. This disconnect can happen even when you’re direct, articulate and honest about what you’re experiencing. There will always be others who judge, invalidate and undermine the reality of your symptoms. This is especially true for those living with invisible illnesses like ME. The emotional toll of not being believed causes deep pain and is extremely traumatic. When disbelief comes from a physician or specialist, it can impede access to health care services and be a detriment to one’s own health. If it happens with friends or family, it can erode relationships. Over time, this creates further isolation and an atmosphere of shame and stigma for the person living with ME. Unfortunately, this is a common experience in the community. It’s also one that has impeded research progress over the decades. To this day, our community is still opposing psychological theories despite the growing body of scientific literature demonstrating physiological abnormalities.

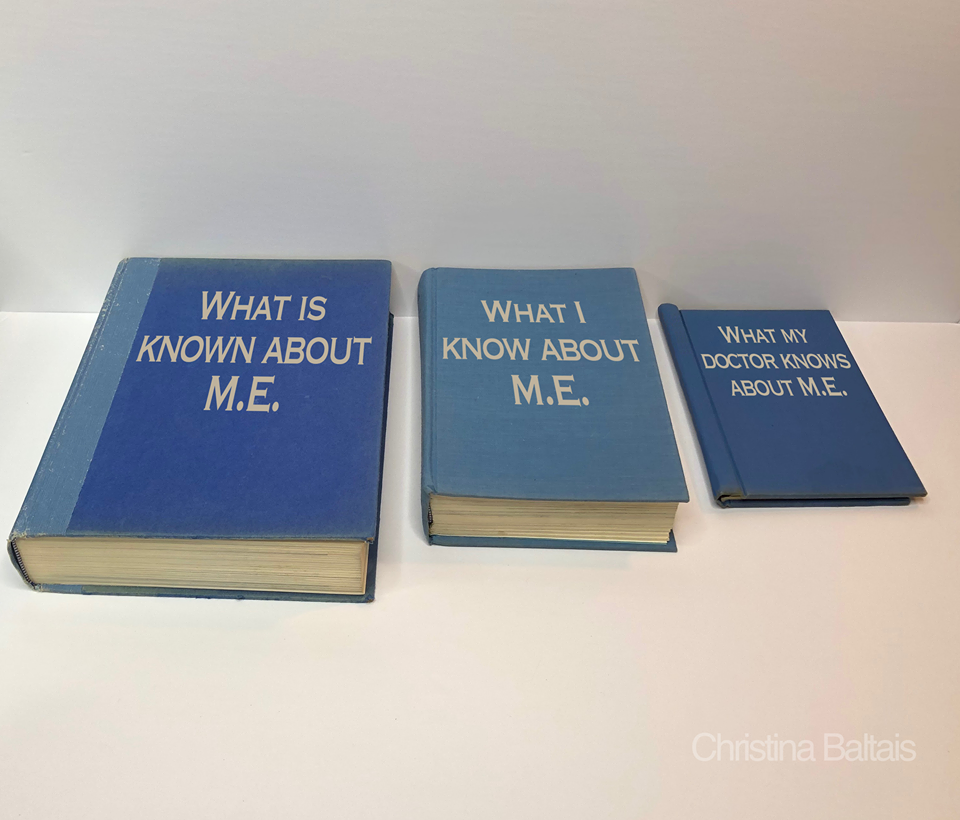

This image highlights the absence of ME in medical school curriculums. It seems the majority of physicians have their first encounter with ME from their exam rooms, instead of classrooms. This creates a knowledge gap, which directly increases the length of time it takes for patients to get a proper diagnosis. This delays critical education to be passed along to the patient, such as pacing (the best strategy known to improve quality of life in people living with ME). This photo also represents how many patients go into appointments, armed with articles and research in hand, in hopes their doctors will learn, understand and help them. When the quality of your life is at stake, becoming an expert on ME is the only rational response. Stuart Murdoch (lead singer of Belle and Sebastian, and ME advocate) summed it up best with this tweet: “My ME/CFS is 30 years old. Happy birthday, ailment! For 30 years I have been trying varied and expensive remedies. The doctors have said ‘well, you know more about this thing than we do’ and ‘I’m not sure I can get behind what you’re trying… but I don’t have any other ideas.’”

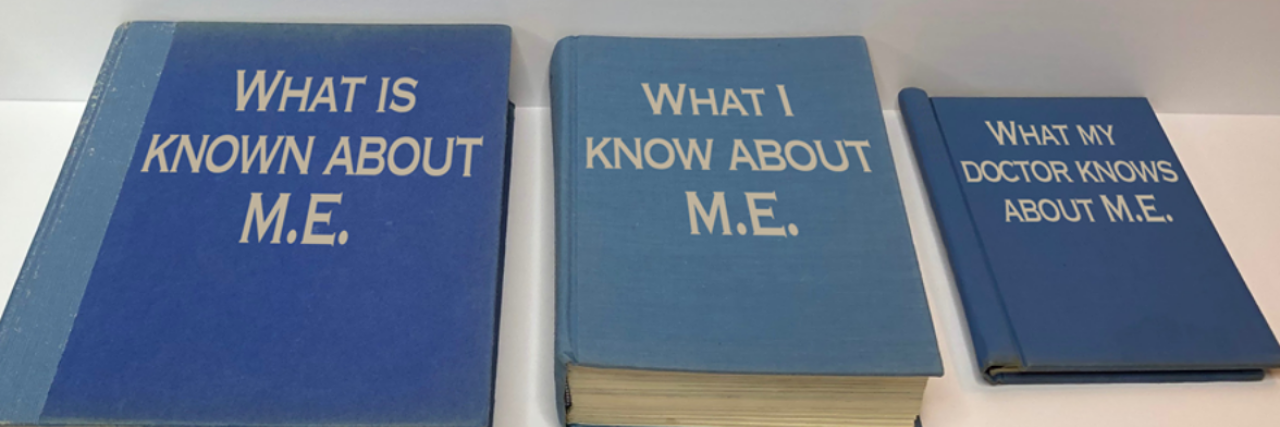

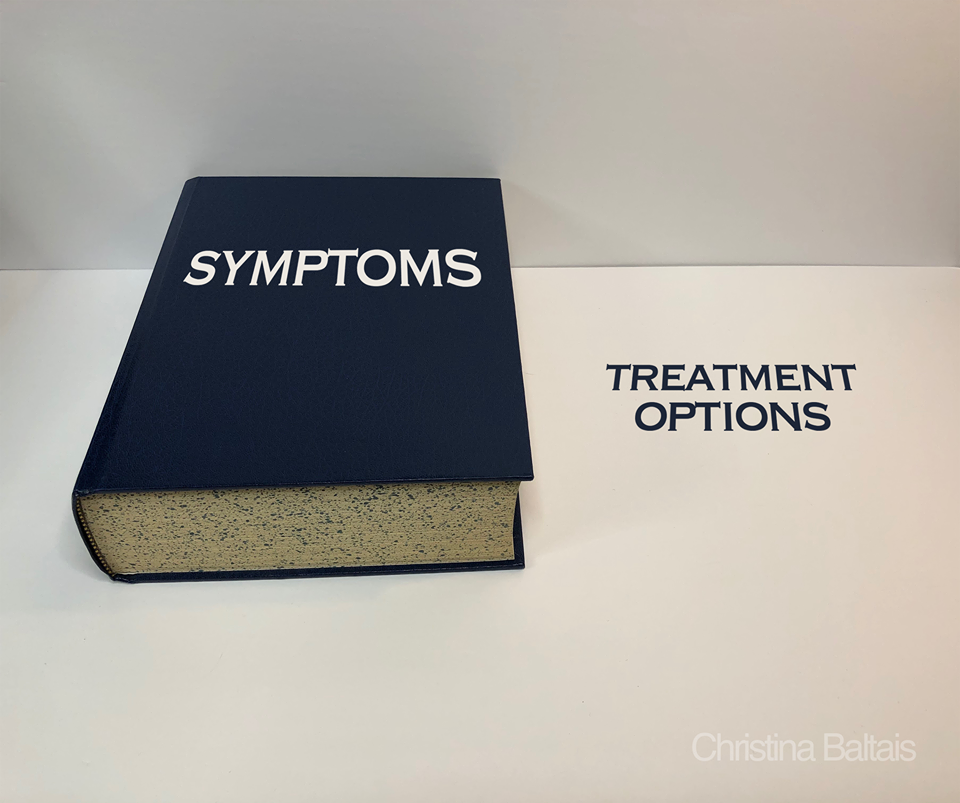

This image symbolizes the experience of being diagnosed with ME, followed by the stark realization that no FDA-approved treatment exists. It’s a nightmarish reality to be plucked from the world and be physically incapacitated, only to be told, “there’s nothing we can do.” For a disease that affects the regulation of the immune system, musculoskeletal system, cardiovascular system, central nervous system, gastrointestinal system, cognitive functioning and auditory/visual centers — this is incomprehensible. ME affects the lives of millions worldwide, and a lack of an FDA-approved treatment is not enough for us.

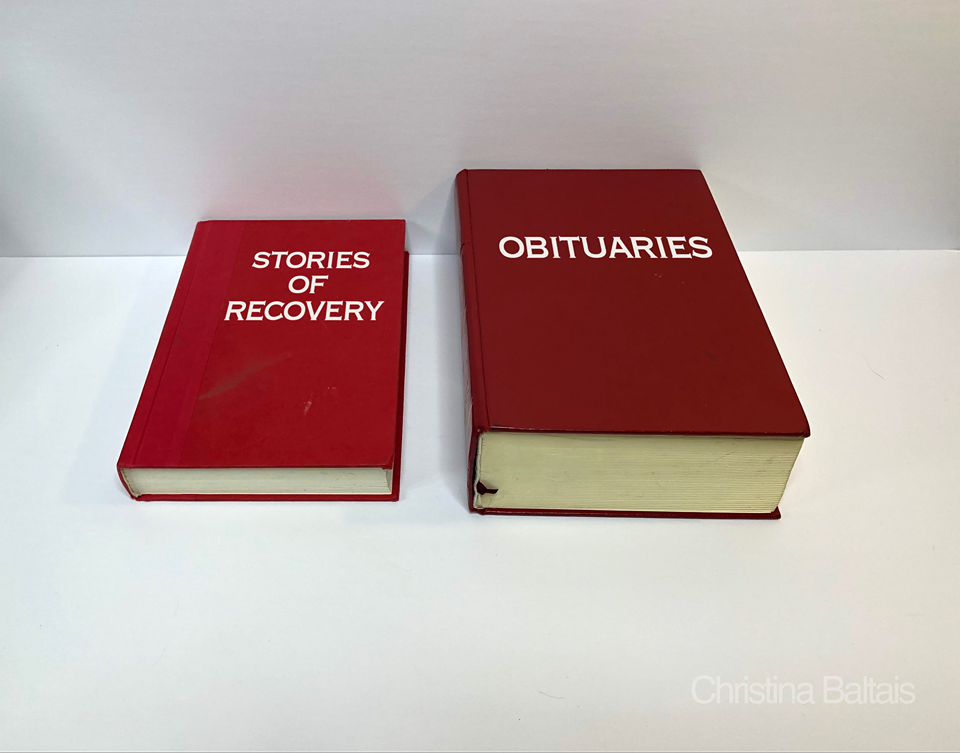

This image strikes a painful chord in our community. ME recovery stories are rare, with estimated rates at only 5%. This means that when you develop ME, the chances of being affected by it for the rest of your life is almost a guarantee. When patients are severely ill and have limited mobility for decades, feelings of despair and hopelessness arise. It is to no surprise that suicide rates are estimated to be six times higher in the ME population compared to the general population. It has been listed as the cause of death in high profile cases like Merryn Crofts and Sophia Mirza. It is heartbreaking, and unless adequate funding is allocated for ME research, we will keep losing our friends.

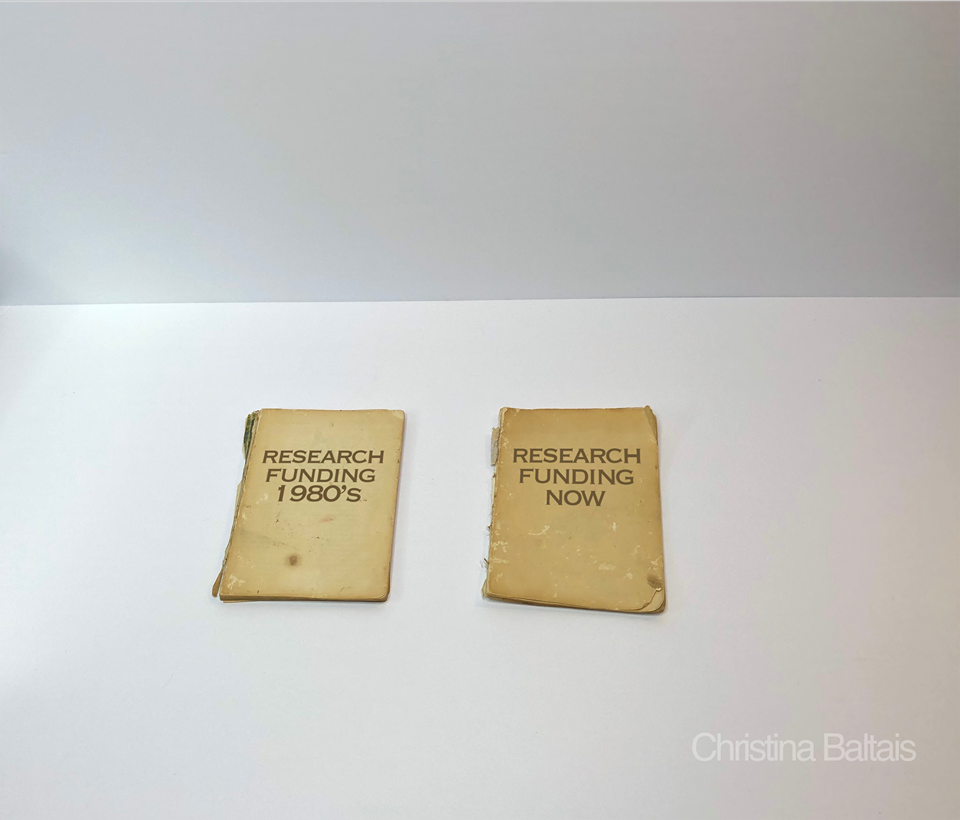

This image highlights the NIH’s (National Institutes of Health) key role in the neglect of the ME crisis since the disease captured headlines in the 1980s. Adriane Tillman, editor for #MEAction writes:

“For the past 20 years, the NIH has funded ME at an average of $5 million per year, which increased to $14 million two years ago. Considering the prevalence and severity of the disease, NIH research for ME/CFS should be at $188 million annually, which is commensurate with diseases of similar burden. If you add up all the funding that the NIH has allocated to ME/CFS research over the past two decades, it wouldn’t reach the total amount that the NIH should be spending on the disease in one year. The absence of research and knowledge about ME/CFS has allowed stigma to maintain a stranglehold on the disease, contributing to confusion, apathy and misinformation around the disease, leading to a complete lack of support for people with ME/CFS from doctors or social services.”

I hope the “ME Anthology Series” has helped shed some light on the current climate of the ME crisis.

Want to help with ME advocacy? Join the #NotEnough4ME Campaign. Want to contribute to ME research? Visit The Open Medicine Foundation. To see Johan Deckmann’s work, click here.

Images via contributor.