I’ve been grappling with whether I should publish this story because it’s a raw experience, and it’s not positive, at least not from my perspective. It’s not that I feel that everything we publish needs to have a positive spin; we deal with reality in all its forms here, but there’s something about not having a way to reconcile the depth of the personal loss this story describes with the losses of others that are in many ways greater.

OK, I know what you’re going to say: there is no productive comparison of personal experiences. All of our struggles are subjective, and that if it’s real and really bad to you, it’s really bad. But that doesn’t mean that I still don’t take pause here. But here goes.

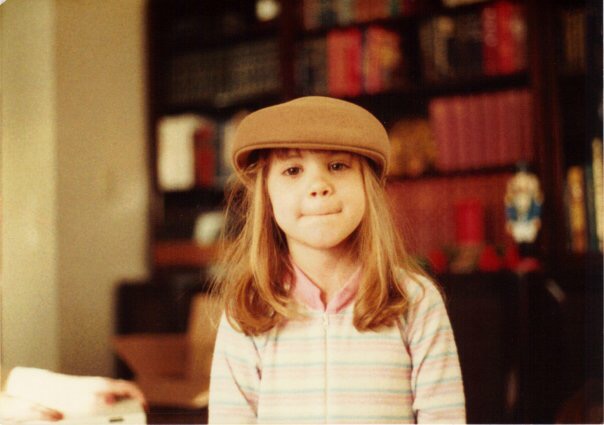

There’s a picture of a little girl at my mom’s house. She’s tucked away in one of a hundred albums’ worth of photos and newspaper clippings and she grows a little with every worn box of memories that you open, a little faded and overexposed in cracking old Polaroids that mark years of her childhood. But in this singular picture, the nearly 40 year old color remains, and the girl is front and center with a half smile and dark eyes. Old eyes. The photograph gave her permanence, but time hasn’t actually forgotten her. Her disease hasn’t forgotten her.

I remember the day my grandfather took that picture. He said, “What do you want to be when you grow up, Krista?” I took his beige wool driving cap and placed it on my head backwards, hipster style, and said, “I’m gonna be a musician.” And there it was. He secured that memory in my own mind and in living color in a shutter flash. It was going to be.

I did grow up to be a musician; it’s one of the many hats that I wear, although now much less frequently than I used to. It’s more than a vocation or even an avocation; it’s a calling and a genetic inevitability. I was born of musicians on both sides of my family, classically trained singers and piano virtuosos and porch singing, guitar strumming hillbillies who played it only by ear. I was born with music in my bones, in my vocal cords, in my lungs— and I was also born with the genetic disposition for autoimmunity that, unbeknownst to that girl in the photo, would begin to strip away the music note by note, breath by breath.

We talk so much about symptoms and symptom management, about living with our conditions. We take our meds on schedule. We share and plan and brainstorm in doctors’ appointments and in our chronic illness communities, in the spaces where these conversations are normal and expected, where we are thankfully one of many with common ground. We hone our coping skills in the places where we know it’s safe to miss a beat — to learn how to live with new or changing situations related to our illnesses. We put on that particular hat, and we keep adjusting it until it fits.

But eventually the hat doesn’t fit despite the adjustment.

I don’t know many musicians who have been able to forget their first on-stage trainwreck. We all have them, and rule number one is that you don’t let on that you made a mistake, that something went wrong. You play on as if nothing happened. But there is nothing like the feeling of missing your first note or dropping a chord, not because you didn’t practice enough or you had one too many Jack and Cokes on break, but because you can’t physically make your hand stretch into the shape of that guitar chord anymore, or because your lungs spasm when you inhale deeply enough to reach the note that used to be effortless. And it happens not gradually over small moments, but in one dramatic realization: “I can’t do that anymore.”

That’s a different kind of train wreck, and one that you wish would only happen amongst people who understand because deep down, you realize that this time it’s not temporary. This time, practice isn’t going to bring it back.

The permanence of your disease – your physical reality – becomes apparent. The budding musician in the picture has come full circle. Soon she won’t be a musician anymore, at least not one who can play. But that also means that she’ll have to re-learn how to grip a kitchen knife without cutting herself, or that she won’t be able to run with her young daughter as she plays outside. Those are the times you’re suffocating under the weight of your situation rather than being able to see the big picture — being able to see what you still can do, rather than focusing on what you can’t. Sometimes, you’re just under it.

So where do you go from there? How do you move forward when symptom management takes a backseat to learning to live with permanent physical limitations? What do you do when something that’s always been an inherent part of you begins to leave you?

I only have questions in this moment. Questions and sadness. I know that I should be grateful that I can still walk, talk, and teach – but despite that very rational consideration, I’m still desperately sad to put my saxophone down for the last time, and to take, piece by piece, music off of my “can do” list…to be packing away something that has been a physical, cognitive, and emotional part of my life for 30 years. So I sit down, and I ask: What do I do with that?