Sherry Young just wanted to be able to walk without pain.

About three years ago, she began to experience sharp pain in her left foot. Her big toe had become crooked and constantly rubbed up against the adjacent toe, making it painful to run, walk or even stand. “I could not walk without intense pain unless I had a pad underneath my toes for cushioning,” Young said.

An orthopedic surgeon told her that he could fix her problem for good. “He thought my foot was hitting the ground too hard and causing pain,” said Young. “That’s what he was trying to correct.”

Though Young had had several orthopedic surgeries, she had always had good insurance and never scrutinized her bills.

At the time of her foot surgery, Young of course knew nothing about hospital charges for surgical screws, medical saws and other hardware used in the operating room.

Then the bill came.

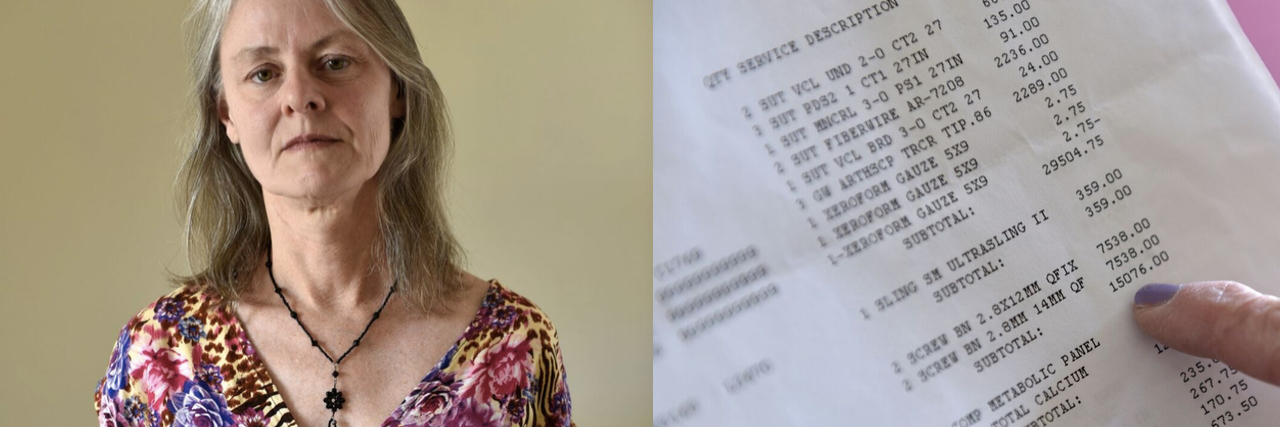

Patient: Sherry Young, 57, a retired librarian on disability and mother of two in Lawton, Okla.

Total Bill: $115,527 for a three-day hospital stay, including $15,076 for four tiny screws — measuring 2.8 millimeters wide and no more than 14 millimeters long — placed in the two middle toes of her left foot.

Service Provider: OU Medical Center, located at the University of Oklahoma Health Science Center in Oklahoma City

Medical Treatment: Young underwent two operations on the same day in June 2017. One surgeon addressed an injury in Young’s shoulder, caused by arthritis and overuse. A second surgeon performed several procedures on her foot, including removing a bone spur. To better align Young’s middle toes, the doctor removed a slice of bone from the center of each toe, and then reconnected the two ends with surgical screws made by Arthrex, a medical device manufacturer based in Naples, Fla.

What Gives: Two weeks after surgery, Young received a letter from her insurance plan, BlueCross BlueShield of Oklahoma, stating that it had not approved her hospital stay. Staying overnight was not “medically necessary,” according to the letter, because foot and shoulder surgery are typically performed as outpatient procedures.

The letter “put me in a panic,” said Young, who was suddenly worried that she would have to pay the entire $115,000 bill herself. That’s about how much her home is worth, and five times her annual income.

Faced with the astronomical cost, Young asked for an itemized copy of her bill and began checking every charge.

She was floored by the price of the screws, each of which cost more than a high-end computer.

“Unless the metal [was] mined on an asteroid, I do not know why it should cost that amount,” Young said.

She repeatedly asked officials at OU Medical Center for part numbers for the screws, so she could find out how much they cost the hospital. Hospital officials never provided the information, Young said.

John Schmieding, senior vice president and general counsel for Arthrex, declined to tell Kaiser Health News exactly how much his company charges hospitals for the type of screws implanted in Young’s foot. But he did offer ballpark figures: “Our sale price for screws used in foot and ankle procedures would be below $300 per screw, with the most expensive around $1,000.”

As for what the hospital charges, Schmieding said, “We do not direct or control how a facility bills for their procedure.” Based on the numbers Schmieding provided, the hospital markup on Young’s screws could range from roughly 275 percent to upward of 1,150 percent.

“It’s mind-boggling,” said Dr. James Rickert, an orthopedic surgeon in Bedford, Ind., and president for the Society for Patient Centered Orthopedics, which advocates for affordable health care. “We are talking about little pieces of metal.”

Yet such steep markups are common at hospitals, said Rickert, who was not involved in Young’s care.

Clearly, the screws used in Young’s surgery are more sophisticated than those sold at the local hardware store. Many of the screws in Arthrex’s online catalog are made of titanium, which is popular for surgery because it’s strong and durable. The screws are also hollow, designed to fit over a guidewire so that doctors can place them in precisely the right place.

Surgical device manufacturers also must comply with strict regulations, said Steve Lichtenthal, vice president of business development at the Orthopaedic Implant Co., based in Reno, Nev., which makes surgical supplies.

But even the fanciest screw is still pretty simple, Lichtenthal said. Tiny screws cost only about $30 to manufacture, and the technology hasn’t changed much in decades, he said. About half the cost of a surgical implant goes toward paying sales and marketing staff, who develop close relationships with doctors and sometimes even attend surgery, Lichtenthal said.

Screws weren’t the only expensive devices figuring into Young’s bill. A drill bit, used for making holes in bone, carried a charge of $4,265; a tool for removing and cauterizing tissue was $5,047; a saw blade, $619.

While screws can be used only once, there’s no reason that other surgical equipment, such as saw blades, should be disposable, Rickert said. Hospitals routinely sterilize tools such as scalpels and scissors, then use them again.

A hospital spokesman declined to comment on the specifics of Young’s bill, as did the surgeon who operated on her foot.

OU Medical Center issued a statement that said: “OU Medical Center provides the highest-quality patient care. We are focused on acquiring the latest tools, treatments and technology, while diligently making sure we have the resources to maintain this commitment our patients deserve. We strive to keep costs down and focus investment on where it really matters — our patients.”

In the statement, OU Medical Center said few patients pay the full price. Instead, insurance companies typically negotiate discounts with hospitals, allowing them to pay less than the amount on the list of charges.

Yet, as Young learned, people who are uninsured — or whose insurance plan refuses to pay — get no discount.

Resolution: Young is now off the hook. In a statement in response to a reporter’s questions, BlueCross BlueShield of Oklahoma said it never actually denied Young’s insurance claim, but simply needed “additional information from the provider in order to process it correctly.”

According to Young’s most recent billing statement from OU Medical Center, she does not owe anything for her hospital stay. However, her latest statement from the hospital includes a $413 charge for an “appeal denied.”

Surgery relieved the chronic pain in her shoulder and alleviated some but not all of the pain in her foot, Young said.

The Takeaway: Companies can charge big prices for small surgical supplies and hospitals can mark them up at will.

If you want to know exactly why your bill is so high, ask for an itemized list of charges. Since patients have no ability to shop around for different screws before the surgery, it’s important to complain loudly to the hospital, your insurer and your employer if you see charges that seem outrageous.

This is a monthly feature from Kaiser Health News and NPR that dissects and explains real medical bills in order to shed light on U.S. health care prices and to help patients learn how to be more active in managing costs. Do you have a medical bill that you’d like us to see and scrutinize? Submit it here and tell us the story behind it.

Jane Greenhalgh produced and edited the interview with Elisabeth Rosenthal for broadcast. Jackie Fortier from StateImpact Oklahoma reported from Lawton, Okla.

Header image via Kathleen Hayden (Kaiser Health News).