Sometimes the news isn’t as straightforward as it’s made to seem. Erin Migdol, The Mighty’s chronic illness editor, explains what to keep in mind if you see this topic or similar stories in your newsfeed. This is The Mighty Takeaway.

When Tom Petty’s cause of death was announced on Friday as an accidental drug overdose involving several medications including opioids, you could almost hear the reactions rolling in: People need to stop using opioids. Petty was obviously an addict. Can’t doctors just stop giving people those pills? Petty should have just toughed it out.

This is the chatter that typically surrounds the opioid crisis, especially when someone dies of an overdose. Deaths like Petty’s are often used to fuel to the idea (usually among people who haven’t consulted chronic pain patients) that in order to curb opioid addiction and overdose, we need to stop allowing people to have opioid medication, and that anyone using it long-term must be addicted. Opioids themselves, as well as the people using them, become the scapegoat.

Yes, we need to fight opioid addiction and the increasing number of lives it’s taking, and part of that is recognizing that many people are purposefully misusing opioids to get high. But Petty’s death is indicative of an issue that doesn’t get discussed enough: the reality that our medical system is failing so many chronic pain patients. Petty needs to be the wake-up call that not including the chronic pain patient’s perspective in the opioid conversation is literally deadly.

The coroner reported that Petty passed away of organ failure and cardiac arrest due to “mixed drug toxicity,” and had fentanyl, oxycodone, Xanax, Restoril (a sedative that treats insomnia) and Celexa (an SSRI that treats depression) in his system when he died. Of course, it’s important to acknowledge that we don’t know Petty’s full story — we don’t know where he got these drugs, who was giving him medical advice, or what he was told about the safety of these drugs. He has a history of heroin addiction, and we don’t know if or how that played into his medical decisions. A statement by Petty’s widow and daughter said they believed the pain Petty had (from a broken hip) was unbearable and was the cause for his overuse of medication. His death was ruled accidental, so whatever medications he took, he likely didn’t know the dosage he took would be deadly.

And that opens up a question we need to be asking ourselves in the wake of his death: Why didn’t he know? Did his doctors tell him, in no uncertain terms, what would happen if he took more than the recommended amount? Did he know the side effects of all of his medications and how they might interact with each other? If he was getting his medications from different doctors, did they ever speak with each other about their patient and make sure they understood everything he was taking and what conditions he was being treated for? Did they monitor him closely and give him extra support since he had already battled heroin addiction 20 years earlier, which creates a strong risk for misusing other drugs?

The drugs Petty, and so many others, are taking, can be dangerous if taken incorrectly, and every patient needs to understand the potential side effects. Synthetic opioids like fentanyl are now the leading cause of death from opioids, doubling from 2015 to 2016 and making up a third of all opioid deaths. Meanwhile, prescription opioids caused 23 percent of opioid deaths in 2016. There’s also a well-documented risk of taking opioids like fentanyl and oxycodone along with benzodiazepines like Xanax. Both types of drugs depress the central nervous system and can lead to death.

The medical system failed Petty if they never fully explained the risks of every medication he was taking, or if they irresponsibly prescribed this medication to him. It’s worrisome to think of other chronic pain patients who may be in the same situation. Do they know what dosages they’re on and what dosages would be deadly? Have they been educated about the side effects and how they combine with other meds? Petty’s death should be a wake-up call to every doctor that they need to make sure their patients fully understand the risks.

This doesn’t have to mean refusing to prescribe pain medication. Most patients who take opioids use their medication responsibly — studies estimate addiction rates for chronic pain patients to be between 1 and 12 percent. The rate of opioid misuse, a broad category including taking medication without a prescription, taking more than prescribed or taking for a reason other than their condition (but not diagnosed with a substance abuse disorder) is slightly higher. The 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health estimated that about 13 percent of people who took opioids misused them, with 63 percent of those reporting that they did so to relieve pain. Cutting pain patients off from opioids completely would be an inhumane and misguided approach.

However, it is possible that Petty was under good medical care and did know the risks of his medication — and still took that elevated dose anyway. This, too, should indicate to us that our medical system is failing chronic pain patients. Why did Petty feel he had no other alternatives besides simply taking more of his opioid medication? Why is a chronic pain patient’s only option for pain relief a drug with such deadly risks? And why, if he was actually obtaining some or all of these medications illegally, did he feel that in order to get the relief he needed, he had to turn look outside the medical system to the illicit drug market?

We need to have more, safer pain relief options than just opioids. Medical marijuana has shown promise as a viable option for patients. Studies have even suggested legalizing marijuana could help decrease opioid deaths. But Attorney General Jeff Sessions recently rolled back a memo protecting states that legalized marijuana, so the future of marijuana as a treatment option remains unclear. Scientists are researching opioids that wouldn’t have the side effects associated with addiction — an intriguing option, but it’s too early to tell if or how this would be helpful to pain patients.

Ultimately, Petty is like so many in the chronic pain community. He had family, friends, a job he loved and a life outside his pain. If we continue to treat the opioid crisis as purely an addiction issue — which requires its own set of responses, like keeping pills from being diverted and addressing root causes of addiction — and not address the challenges chronic pain patients deal with in their quest for pain relief, then we may see more cases like Petty.

Chronic pain patients simply cannot afford to be left out of the conversation. Their needs must be a part of the solution.

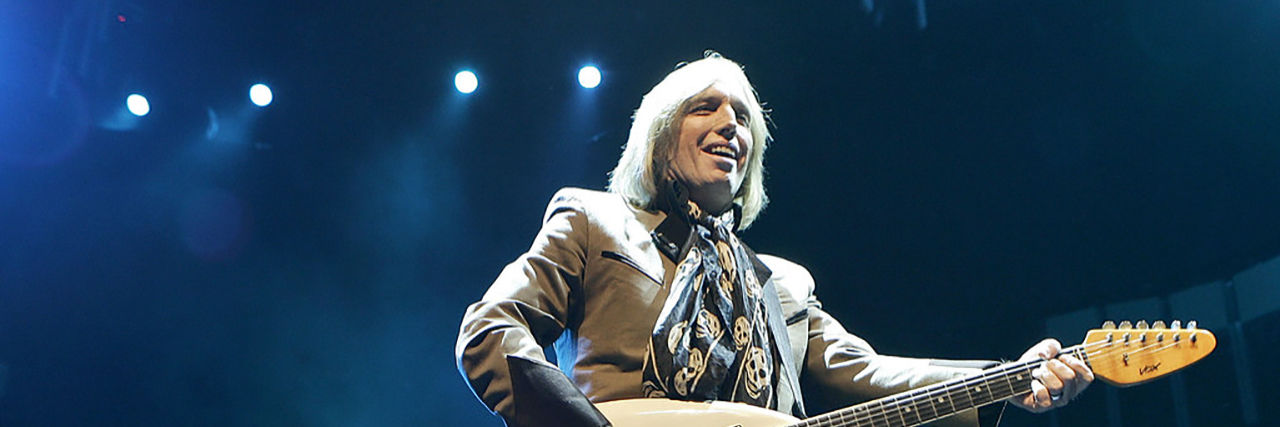

Image via Creative Commons/Mexicaans fotomagazijn