The pandemic isn’t over, and COVID is still killing people.

No, we’re not trying to spook you.

The pandemic is still ongoing. And COVID is currently on the rise again. What’s happening is genuinely concerning. Even as the world buzzes about “return to normal” (what does “normal” even mean?), the virus hasn’t stopped. Thousands of people are still hooked to machines in ICUs, fighting for their lives, while many others are wrestling with what the virus left behind. The threat? Still very much alive. And the sad reality? The world is marching forward, but we have forgotten our most vulnerable.

“But It’s No Longer a Public Health Emergency”

True. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared an end to the global emergency phase of the pandemic.

However, WHO’s director-general, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus emphasized that the declaration does not mean that the threat is over, adding, “The worst thing any country could do now is to use this news as a reason to let down its guard, to dismantle the systems it has built, or to send the message to its people that COVID-19 is nothing to worry about.”

And yet, that’s exactly what happened. Several countries, including the United States, lifted all mandates and restrictions applied during the public health emergency (PHE).

The virus still lives among us, targeting vulnerable people more than ever. Think about your grandparents, your neighbors managing health challenges, and friends who aren’t able to get vaccinated. They are at an even greater risk now that protective measures have been removed.

“Why Are People Still Dying?”

In the first five months of 2023, the United States reported more than 37,000 COVID-related deaths, almost as much as flu data for a year. As the virus continues to evolve, a highly transmissible new variant, EG.5, now accounts for the country’s largest proportion of COVID infections. The spread comes as U.S. reports its first increase in hospitalizations of this year. More than 9,000 people were hospitalized with COVID in the last week of July, up from about 6,300 at the end of June.

COVID has never affected everyone the same way. Some folks, like older people, people with chronic illness, disabilities, and those with weaker immune systems, are still more likely to get seriously sick. Also, we have yet to be able to make the best use of the tools available because we as a society haven’t been great at telling people about the changing risks during this ongoing pandemic.

Here’s why some people are more vulnerable than others:

1. Weakened Immune Systems

Those with pre-existing or immunocompromised health conditions often have weakened immune systems. This makes us more susceptible to infections, including COVID, and more likely to experience severe illness or complications once exposed.

2. Age-Related Vulnerability

Older adults are more prone to severe illness due to COVID because the immune system naturally weakens with age. Many older adults may also have underlying health conditions that further increase their vulnerability.

3. Comorbidities

Some pre-existing health conditions can exacerbate the effects of COVID. These conditions can make it harder for the body to fight off the virus, and harder to recover.

4. Limited Access to Health Care

Many people, particularly those in lower-income or marginalized communities, may face barriers to timely and appropriate health care. This can result in delayed diagnosis, inadequate treatment, and poorer outcomes if they contract COVID. This is also true for people who avoid hospital environments as it increases their risk of infection.

5. Vaccine Effectiveness

While vaccines have proven to be highly effective in reducing the risk of severe illness and death from COVID, they might not provide the same level of protection for people with weakened immune systems. Some immunocompromised people might not mount a robust immune response to the vaccine, leaving them more susceptible to the virus, even after they have been vaccinated.

6. Variants of the Virus

Several SARS-CoV-2 virus variants have emerged over time. Some variants are more transmissible and might partially evade immunity from previous infections or vaccinations, potentially affecting certain groups more severely.

7. Care Settings

Some people with disabilities or underlying health conditions reside in care settings where close contact with others is unavoidable. This increases the risk of transmission within these settings and can lead to severe outbreaks.

8. Behavioral Factors

Adherence to public health guidelines, such as mask-wearing, social distancing, and hand hygiene, is crucial in preventing the spread of the virus. However, with no protective mandates, more people are vulnerable to contracting an infection, even if they are masking.

9. Vaccine Uptake

Lower vaccination and booster rates hinder efforts to achieve herd immunity, leading to ongoing transmission and increased vulnerability among at-risk populations. Although the U.S. reports that over 80% of the population has received at least one vaccine dose, it is important to know the efficacy wanes with time, and the virus is constantly evolving. Only 17% of the U.S. population has received bivalent boosters. When a significant percentage of the population doesn’t get updated boosters, it further limits our ability to achieve herd immunity and continues to put vulnerable people at risk.

“If People Are Really Dying, Why Are We Not Hearing About It?”

When WHO’s Tedros addressed the press in May, he shared, “Last week, COVID-19 claimed a life every 3 minutes, and that’s just the deaths we know about.” When we don’t have the complete picture, it is hard to publicize it. You are not hearing about it because so many testing and tracking measures have been removed, so we can no longer access the big picture.

Is COVID on the rise again? Recent signals from wastewater surveillance in the U.S. show a surge in COVID prevalence. Before it even shows up in our hospitals, we see its shadow in our sewers, indicating that the virus is still very much in our midst. Hospitalizations in certain areas are ticking upward, a haunting echo of days we hoped was behind us.

Tracking this surge is becoming increasingly challenging. Data reporting and tracking changes can blur the clearer picture we once had. The broader population may remain blissfully unaware, but our high-risk communities acutely feel the weight of these numbers.

The real question is, why don’t we have the same access to data? Here are some reasons:

1. Decreased Testing and Reporting

During a public health emergency (PHE), there is often an increased focus on testing and reporting cases. When the emergency ends, testing efforts might decrease, leading to fewer reported cases. This can give a false impression that the virus is under control when it is still present at lower levels.

2. Underestimation of Spread

If testing and reporting decrease after the end of the emergency, the true extent of virus transmission may be underestimated. Asymptomatic or mild cases might go undetected, leading to an inaccurate representation of the virus’s prevalence in the population.

3. Reduced Public Awareness

Declaring a PHE often leads to heightened public awareness and adherence to preventive measures. Once the emergency is over, people might become complacent and relax their efforts, potentially leading to a resurgence in cases.

4. Delayed Data Collection

The ending of a PHE might lead to delays in data collection and reporting. Health agencies and organizations might shift their focus to other priorities, slowing down the processing and dissemination of COVID data.

5. Disruption in Data Sharing

During an emergency, there is usually a coordinated effort to share data among various health care organizations, research institutions, and governments. Once the emergency ends, these collaborations might lose momentum, decreasing the availability of comprehensive and up-to-date data.

6. Shift in Attention and Funding

As the emergency subsides, attention and funding might shift to other public health concerns. This could impact the resources allocated to COVID data collection, analysis, and reporting, potentially leading to gaps in monitoring.

7. Inconsistent International Data

International collaboration in data sharing and reporting might also decline after the emergency is declared over. This can result in inconsistent data between countries, making it challenging to assess the global situation accurately.

8. Emergence of Variants

The ending of a PHE does not necessarily mean the end of virus mutations and the emergence of new variants. Tracking and understanding the spread of variants require ongoing surveillance, which could be compromised if data collection efforts are scaled down.

The PHE gave the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) the authority to compel testing laboratories to report their COVID test results or states to report number of vaccinations. When the PHE ended, the CDC lost the authority, impacting how the agency collects and aggregates data. All those visualizations and trackers we used to stare at in 2021 no longer represent the whole picture because that picture isn’t available in the same way.

Even the number of hospitalizations and deaths does not give an accurate picture since it only accounts for the most critical cases. Even with agencies sharing the results of COVID tests, test positivity rates may be less reliable. Reports of COVID-related deaths in the most recent weeks are also incomplete, so it is hard to determine the rising infection rate.

“But We’ve Had Three Boosters”

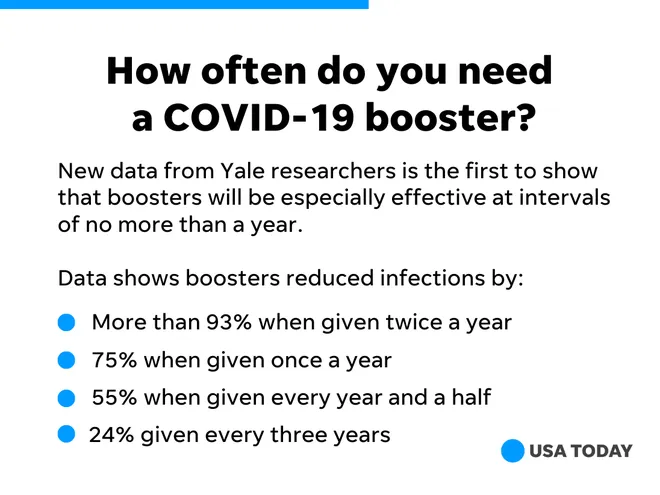

A recent Yale study suggests that healthy people should get annual COVID boosters to prevent widespread outbreaks. The co-authors said, “Roughly 3 in 10 people will get infected with COVID-19 even with an annual shot. But 9 in 10 will be infected without such updates. Not getting boosted triples the risk for infection over six years.”

If the virus keeps evolving, vaccines should too. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently advised drugmakers to update the shots to target XBB.1.5 and other variants.

Updated boosters for healthy and at-risk populations can help protect more people from contracting the new strains. An updated booster is expected this fall.

“Why Don’t They Just Wear a Mask?”

While masks offer protection to the wearer, their primary function, especially in the case of cloth masks, is to prevent the wearer from spreading the virus to others. When an infected person wears a mask, they significantly reduce the potential of expelling respiratory droplets that might contain the virus. This means that while vulnerable people can wear a mask to protect themselves to some extent, they are best protected when everyone wears one.

Indoor spaces with limited ventilation pose a higher risk of COVID spread. In such environments, even if a vulnerable person wears a mask, they might still be at risk if others around them do not. Shared air in confined spaces means respiratory droplets can linger, heightening the risk of transmission.

The pandemic has taught us many things, and chief among them is the understanding that our actions have far-reaching impacts on our broader community.

When we wear a mask, we are choosing community, compassion, and collective well-being over individual convenience.

What Is Long COVID?

As the years have progressed, it’s become evident that for many, the battle with the virus doesn’t end after the acute phase has passed. This prolonged experience, termed “Long COVID” or “Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC),” is beginning to paint a more complex picture of the virus’s impact on our bodies and lives.

Long COVID refers to a range of symptoms that continue for weeks or months after the acute phase of a COVID infection has resolved. It can affect anyone — those hospitalized with COVID and those with mild initial symptoms.

The manifestations of Long COVID are diverse and can vary in intensity. Some common symptoms include:

- Fatigue: Persistent, often debilitating tiredness that doesn’t improve with rest.

- Respiratory Issues: Breathlessness, cough, and chest pain.

- Cardiovascular Problems: Palpitations or even signs of myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle).

- Neurological and Psychological Effects: Brain fog, memory lapses, difficulty concentrating, anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbances.

- Musculoskeletal: Joint pain and muscle aches.

- Gastrointestinal Issues: Nausea, diarrhea, and appetite loss.

Understanding Long COVID is not just crucial for patients; it has broader implications for health care systems, workplaces, and societal structures:

Health Care Provision: There might be a need for long-term care resources and specialized clinics for Long COVID patients.

Work and Productivity: Affected individuals may have trouble returning to work in their previous capacity, impacting productivity and requiring workplace accommodations.

Social and Emotional Well-being: The social and emotional toll of prolonged illness can be immense, highlighting the need for mental health support.

Imagine battling a chronic condition, say diabetes or asthma, and just when you’ve found your rhythm, another storm — COVID — hits. For many, this isn’t just a hypothetical; it’s reality. Picture the fatigue that already comes with managing daily medications, doctor visits, and lifestyle adjustments. Add Long COVID’s unrelenting exhaustion, brain fog, and breathlessness. For those with pre-existing conditions, the battle isn’t just physical. There’s an emotional and mental aspect to it.

Every new symptom brings a flurry of questions: Is this my original condition acting up, or is it the aftermath of COVID? The intertwining of existing health challenges with the unpredictability of Long COVID can feel like navigating a labyrinth without a map. Amidst the medical jargon and endless tests, it’s about real people and their stories.

The Mirage of Normalcy

The term “mirage” is apt. In deserts, a mirage is a visual illusion where thirsty travelers perceive distant water, driven by their deep desire to drink. Similarly, as the initial shock of the pandemic wears off and patches of daily life regain some semblance of the “old normal,” it’s tempting to believe that we’ve returned to safe, familiar ground.

However, data and science caution us otherwise. Sporadic surges, emerging variants, and the challenges of global vaccine distribution remind us that the pandemic, while perhaps less visually omnipresent, is far from over. Those in vulnerable groups continue to live in heightened states of caution. The lingering effects of Long COVID remain a puzzle to be solved.

Why does this mirage of normalcy matter? Because perception shapes behavior.

COVID’s epilogue still needs to be rewritten. The path forward demands a recalibration of our notions of “normal.” It’s a clarion call to merge personal choices with shared responsibility and to ensure that the vulnerable aren’t left to languish in the pandemic’s wake. The narrative continues, and each decision shapes its trajectory.

The current chapter isn’t closure; it’s a pivot, a demand for collective vigilance. We repeat the pandemic isn’t over.

Getty image by Catherine Delahaye